Abstract

In contemporary organic synthesis, substances that access strongly oxidizing and/or reducing states upon irradiation have been exploited to facilitate powerful and unprecedented transformations. However, the implementation of light-driven reactions in large-scale processes remains uncommon, limited by the lack of general technologies for the immobilization, separation, and reuse of these diverse catalysts. Here, we report a new class of photoactive organic polymers that combine the flexibility of small-molecule dyes with the operational advantages and recyclability of solid-phase catalysts. The solubility of these polymers in select non-polar organic solvents supports their facile processing into a wide range of heterogeneous modalities. The active sites, embedded within porous microstructures, display elevated reactivity, further enhanced by the mobility of excited states and charged species within the polymers. The independent tunability of the physical and photochemical properties of these materials affords a convenient, generalizable platform for the metamorphosis of modern photoredox catalysts into active heterogeneous equivalents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photoredox catalysis refers to an energy-conversion process in which the absorption of photons by a substance triggers electron transfer. In the past decade, the application of this phenomenon to organic synthesis has evolved from an academic curiosity to an enabling technology widely adopted in pharmaceutical synthesis1,2,3,4,5,6,7. By coupling photoexcitation with other molecular processes, including cooperative catalytic schemes8,9,10, hundreds of powerful and previously inconceivable organic transformations have now been realized. However, compared to the rapid discovery of new photon-dependent reactions, the implementation of these processes on large scale has seen only limited progress due to the high cost of many photocatalysts, challenges in catalyst removal, and restricted light penetration in traditional batch reactors11. Thus, the conception of new technologies12,13,14,15 that generally enhance photoredox catalysis on scale is a pressing goal that has attracted immense research effort.

Photoredox catalysts can be divided into two major groups (Fig. 1a): homogenous materials, which are soluble in the solvents typically used for photoredox catalysis, and heterogeneous, which operate as insoluble solids. Due to ease of synthesis and tunability, the vast majority of newly developed catalysts belong to the former group, which includes small-molecule organic dyes3, such as perylene diimides (PDIs), and organometallic complexes5, such as Ir(ppy)3. Meanwhile, heterogeneous catalysts have the advantages of facile removal from reaction mixtures and recyclability, which are important from both cost and sustainability perspectives6,11. Well-known examples include two-dimensional (2-D) surface photocatalysts, especially semiconductors16 such as mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-CN)17, and porous three-dimensional (3-D) constructs, such as metal-organic/covalent organic frameworks (MOFs/COFs)18,19,20. The appealing characteristics of these materials arrive at the expense of diversity and tunability: there is often no rational technique to finely alter their photochemical properties while retaining the bulk physical properties. Importantly, the inability of most heterogeneous catalysts to be cast into films or coatings from liquid or solution phase is a considerable practical limitation, particularly towards their synergistic application with emerging technologies such as continuous-flow synthesis10,11.

A strategy that allows synthetic chemists to simultaneously take advantage of the respective desirable properties of homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts would be exceptionally empowering. We proposed that one solution might involve a general method for converting any member of the vast toolbox of soluble photocatalysts into equivalent insoluble materials, while maintaining the original photochemical attributes and activity. However, to our knowledge, no heterogenization approach exists with broad scope both in the kinds of dyes incorporated and in the types of catalytic materials accessible. Although several examples of photocatalyst immobilization on insoluble solids have been demonstrated21, each strategy addresses only a small subset of chromophore structures, and the vast majority of supported catalysts lack solution-processability, severely limiting the operational modes that are available (typically only particles or dispersions).

Herein, by extending our recently reported Pd-catalyzed polycondensation reaction22, we present a method that, in principle, allows for any organic or organometallic photocatalyst to be heterogenized through copolymerization with porosity-promoting bulky organic monomers (triptycenes and spirobifluorenes)23,24,25. We note that while 2D and 3D extended materials are well represented among heterogeneous photocatalysts, examples of one-dimensional (1D) photocatalysts, in which the active components form chains, are relatively rare26,27. Importantly, our linear-polymer structures, while insoluble in the solvents typically employed for photoredox catalysis, remain highly soluble in a few, select handling solvents (DCM and THF). As a result of this processability, our immobilization technique is not restricted to any particular target mode of heterogeneous catalysis but can conveniently access a wide range of known morphologies, including dispersions, films, coatings, textiles, and magnetic nanoparticles.

Aside from solution-processability and broad generality, our 1D polyether platform offers additional valuable benefits compared to existing heterogeneous photoredox catalysts. First, the solubility of organic polymers enables simple characterization of structure, molecular weight distribution, photocatalyst loading, defect concentration, and batch-to-batch quality variations, all of which are often impractical to analyze for conventional insoluble catalysts. Second, traditional materials relying on non-covalent interactions for dye attachment, or labile covalent bonds such as Si–O or Al–O bonds, can exhibit poor chemical stability21. In contrast, the polymers developed in this work exhibit exceptional thermal stability and inertness toward a variety of chemical conditions. Third, the immobilization of small-molecule catalysts on heterogeneous supports often leads to drastically decreased turnover frequencies; however, with our polymer materials, due to a combination of reduced aggregation-induced quenching, highly porous-polymer structure, and energy- and charge-transport processes, very efficient catalysis can be achieved, in some cases with rates exceeding than with the corresponding monomers. Finally, the design of our polymers enables independent control of the physical and photochemical properties without alteration to the synthetic procedure.

Results and discussion

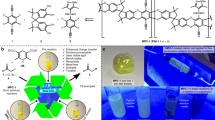

Our recent systematic study22 showed that the foundational building blocks of our proposed material, t-Bu-triptycene hydroquinone 1-A and spirobifluorene dibromide 1-B, could be cross-coupled to form polymer 1 with excellent molecular weight, polydispersity, porosity, and film properties (Fig. 2a). Through slight alteration of these prior conditions, we were able to introduce chromophore-containing comonomers to generate materials with similar physical attributes as 1, but with added photocatalytic capabilities. As a model, we selected the classic dye perylene diimide (PDI) as synthetically versatile redox-active moiety28. With the addition of 10% of PDI dibromide (1-C) in the polycondensation process, we obtained a near-quantitative yield of a deep-red solid (1-PDI) with high molecular weight and moderate polydispersity. The porosity was evaluated through the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) gas adsorption method, revealing a considerable specific surface area (SSA) of 338 m2/g. The essential role of the triptycene units in endowing the polymer with this exceptional porosity is evident from the very low SSA of related polymer 1-PDI-HQ, in which para-phenylenes are present instead. Based on the N2 adsorption isotherm, the estimated pore size distribution was concentrated in the microporous range (<2 nm, Supplementary Fig. 3-1). Furthermore, the polymer showed excellent thermal and chemical stability under controlled conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4-2). The extent of incorporation of the PDI was determined by 1H NMR analysis to be 10%, in agreement with the fraction of monomer employed during the synthesis.

a Synthesis of 1, 1-PDI, and 1-PDI-HQ. See the Supplementary Information for detailed conditions. b Photophysical properties. c Light-driven reversible redox process with an amine partner. d Kinetics of catalytic photo-oxidation model reaction. BET = Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method. aToo low to be reliably determined from N2 adsorption isotherm. bDilute THF solution (1.0 × 10–5–5.0 × 10–7 M). cSolid state (powder).

The absorption and steady-state photoluminescence spectra of 1-PDI contained distinctive features (λmax = 523 nm, λem = 528 nm in THF solution) characteristic of PDI units (Fig. 2b). The solid-state photophysical properties of 1-PDI showed notable differences when compared against monomeric (PDI-Mono) and non-porous (1-PDI-HQ) analogues. Although the molecular dye displayed a very low fluorescence quantum yield in the solid state (QY = 0.02), the chromophores covalently hosted within triptycene-containing frameworks were bright emitters (QY = 0.29 for 1-PDI), indicating a reduction in aggregation-based quenching. Monomeric PDIs are known to exhibit a substantial emission red-shift upon aggregation29, and we found that the difference in emission maxima between solution and solid states was substantially smaller for the polymers than for monomers and, in particular, smallest for the porous 1-PDI.

As a test of the photo-activated reactivity of these polymers, irradiation of a DCM solution of 1-PDI with excess Et3N resulted in isosbestic conversion to a new species, with spectral features indicative of PDI radical anions (Fig. 2c)30. Exposure of the resulting solution to atmospheric oxygen regenerated the original polymer over the course of 2 h. Given its promising reversibly stoichiometric reactivity, a dispersion of the catalyst in methanol was evaluated in a simple aerobic photo-oxidation reaction31 of methyl phenyl sulfide (2a, Fig. 2d). At remarkably low loading of catalyst (0.018 mol%), full consumption of starting material could be observed after 6 h. Parallel experiments at equivalent optical densities of a non-porous analogue (1-PDI-HQ) and a monomeric PDI (PDI-Mono) proceeded at a significantly lower rate and only preceded to 80 and 76% conversion over the same time period. An additional control using a combination of PDI-Mono with dye-free polyether 1 (premixed in dichloromethane solution, then dried and dispersed in methanol) showed a reaction rate similar to using PDI-Mono alone. The reactions did not progress during a 30 min interval with no LED irradiation, confirming that the chosen transformation requires continuous photoirradiation. We hypothesized that, in addition to the steric insulation from aggregation-based quenching, the elevated activity of 1-PDI is partially the result of the photoexcited state “hopping” between different dye centers, thereby enhancing the probability of encounter with a substrate or cocatalyst. Indeed, using fluorescence polarization spectroscopy, we observed quencher-dependent behavior consistent with considerable excited-state energy transfer between dye units (for extended discussion, see the Supplementary Information, Section 10.2, Figs. S7-2–S7-4). The mobility of charged states throughout the porous polymer can similarly contribute to an enhanced efficiency. In bulk conductivity measurements, we showed that irradiation of a film of 1-PDI in the presence of triethylamine results in an instantaneous and reversible increase in conductivity (Supplementary Fig. 7-5), suggesting facile transport of negative charges between PDI units.

To illustrate the synthetic versatility of porous linear-polymer catalysts, we applied 1-PDI to a representative range of modern photoredox transformations (Fig. 3a). On a 1.0 mmol scale, the aerobic oxidation of thioether 2a to sulfoxide 3a was accomplished in 95% yield using an alcoholic dispersion of 1-PDI and irradiation with a 450 nm LED. Photoreduction reactions could be performed through the in situ generation of PDI radical anion under inert atmosphere29. Using triethylamine as the terminal reductant, aryl bromide 2b was successfully hydrodehalogenated. The same catalyst could induce atom-transfer radical addition reactions to alkenes: fluorinated alkyl bromide 3c was prepared in high yield from 5-bromo-1-pentene (2c) and perfluorooctyl iodide32. Since 3c is a non-commercial fluorosurfactant essential to other research in our laboratory, we pursued a scaled-up synthesis enabled by catalyst 1-PDI. Over 12 g of product could be obtained in a single run, demonstrating the applicability of these porous materials in a preparative setting. Heterogeneous photoredox conditions were also applicable in polar addition to alkenes, as shown by the anti-Markovnikov hydroetherification of 2d33. In another activation mode, the oxidative C–H functionalization of electron-rich arene 2e was conducted using potassium bromide as the bromine-atom source17. Both oxidative and reductive modes of radical generation were successful using 1-PDI as a photocatalyst, and regioselective addition of these radicals to heteroarenes was accomplished (3f and 3g)34,35.

a Performance of 1-PDI across various reaction classes. b Recyclable usage of 1-PDI as a coating on a glass vial in the photo-oxidation of 2a. c Recyclable usage of 1-PDI deposited on cotton in the photo-oxidation of 2a. d Coated superparamagnetic silica nanoparticles. e Continuous-flow synthesis using a film of 1-PDI in glass tubing.

Many valuable modes of heterogeneous catalysis are accessible due to the solubility profile of poly(arylene ether)s. Using a standard rotary evaporator, a thin film layer could be deposited on the bottom portion of a glass reaction vial, which has maximal exposure to the light source (Fig. 3b). The coated vessel could be conveniently reused to perform the photo-oxidation of 2a, with negligible change in reaction yield over five cycles. Textile-supported organocatalysts have recently been advanced as convenient promoters for acid- and base-dependent reactions36. We showed that 1-PDI can be robustly deposited onto cotton, and that the resulting fluorescent fabric is also a reusable photo-oxidation catalyst (Fig. 3c). The polymer coating could adhere strongly to silica nanoparticles bearing a superparamagnetic iron oxide core (Fig. 3d), which facilitates separation from reaction mixtures for which filtration is impractical. The resulting red powder was an effective agent in photoredox reactions, and the application of a handheld permanent magnet allowed for rapid and complete separation of the catalyst from the methanol solution (Supplementary Movie 1). The catalytic layer could be instantly desorbed from the surface by immersion in tetrahydrofuran and thus recovered from the silica (Supplementary Movie 2).

Continuous-flow synthesis, referring to processes performed within narrow tubing under constant material input and output, has attracted significant attention as an alternative to traditional batch chemical processes37,38. Flow systems are associated with superior heat exchange, mixing, reproducibility, and safety profiles39. The narrow-channel configuration of the reactors has proved particularly promising in large-scale photocatalysis applications, as enhanced light exposure is afforded with decreased risk of over-irradiation that can induce unwanted side-reactions40. A solution-processable material for the immobilization of diverse photocatalysts along the interior surface of the reactor tubing would provide two main advantages. First, no separation of the dyes from the mobile phase would be required after the reaction. Second, by concentrating the chromophores close to the exterior of the reaction mixture, light exposure could be enhanced. Taking advantage of the excellent film-forming characteristics of our porous polyethers, we showed that flow chemistry could be conducted using a photoredox-active coating as a stationary phase (Fig. 3e). To the coolant coil of a spiral reflux condenser, a standard piece of equipment in laboratories that perform microscale organic synthesis, was applied a thin layer of 1-PDI as a solution in THF, drying with gentle heating and air flow. With the system under constant irradiation with blue LEDs, reactants for the C–H bromination of 2e were pumped into the coil using a syringe pump (approximate residence time of 60 min). At steady state, a good yield of 3e was measured in the output stream.

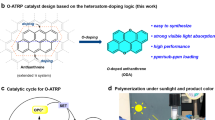

A unique advantage of linear polymers as an immobilization platform is the ability to independently adjust the backbone-derived physical characteristics and the chromophore-derived photochemical attributes (Fig. 4a). Achieving adhesion to fluoropolymer surfaces was desirable since inert, flexible substances such as perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) plastics are the most common tubing materials for modern continuous-flow synthesis. Since most poly(arylene ether) polymers such as 1-PDI adsorb poorly to fluorinated surfaces, and therefore do not form high-quality films, we wondered if we could enhance the attractive interaction through post-polymerization functionalization of the backbone. We subjected the polymer to C–H fluoroalkylation conditions with photogenerated perfluoroalkyl (n-C17F35) radicals to obtain 1-PDI-C17F35 with relatively high fluorine content (F/C ratio = 1:4 by XPS). This new polymer was successfully deposited on narrow inner diameter (1/16 in) PFA tubing and effectively employed as a catalytic stationary phase in the flow synthesis of 3e (Fig. 4b).

a Convenient and independent alteration of catalyst properties. b Post-polymerization functionalization of the backbone enables adhesion to fluorinated surfaces for photoredox catalysis. c Structural variation in the photocatalytic moiety: incorporation of common photoredox chromophores. Numbers in parentheses indicate photoluminescence quantum yields in dilute THF solution (1.0 × 10–5–5.0 × 10–7 M). d Example reactions using modified photocatalysts. aMolecular weight distribution measured on 1-Bpy prior to Ir incorporation. PMDETA = 1,1,4,7,7-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine.

The identity of the covalently-included dye and its doping concentration could be adjusted arbitrarily with little effect on the porosity, solution-processability, and film-forming properties of the polymer. The substitution of other groups in lieu of PDI is synthetically straightforward and requires essentially no procedural modifications (Fig. 4c). Perylenes are highly reducing photocatalysts that have been used in applications such as light-activated atom-transfer radical polymerization (photo-ATRP) reactions41. Using perylene-containing 1-Per as a catalyst, the polymerization of methyl methacrylate could be performed using sunlight as the energy source. With minimal optimization, the poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, 4a) product could be obtained with good molecular weight and polydispersity. Furthermore, the catalytic polymer was easily separated from the product polymer, as the former is strictly insoluble in acetone. The outcome of photo-ATRP can be greatly improved by changing the chromophore and adding a copper cocatalyst. Using phenothiazine 1-PTZ, a controlled radical polymerization reaction of methyl acrylate was achieved, with polydispersity as low as 1.04. These optimized results compare favorably to those using state-of-the-art conjugated microporous phenothiazine catalysts42, which are also significantly more cumbersome to process and to characterize in terms of active site structure and density.

By altering the excited-state redox potentials of catalysts, the preferred mechanistic pathway of a reaction can be switched. Previous studies of the hydroetherification of 2d have revealed that the use of different organic photocatalysts can engender divergent regiochemical outcomes32. Above, we showed that linear product is exclusively formed when using 1-PDI as the photocatalyst. When, instead, the pyrene 1-Pyr and long-wave UV (365 nm) irradiation were used, high branched selectivity was observed (3d’), attributable to the favorability of a photo-reductive, rather than oxidative, route.

In addition to the organic catalysts described above, organometallic dyes can also be easily incorporated through polymer post-functionalization. We were able to coordinate iridium to a porous bipyridine-based material (1-Bpy-Ir), producing chelated iridium complexes that resemble prototypical organometallic photocatalysts7. Iridium photocatalysts can initiate and maintain a Ni(I/III)-based catalytic cycle for Buchwald–Hartwig C–N cross-coupling43,44, a staple transformation in pharmaceutical research and development. Using a low loading of 1-Bpy-Ir in conjunction with catalytic NiBr2, the amination of an aryl bromide was accomplished in a clean and high-yielding manner (product 4b), without the requirement for any additional ligand for nickel. Finally, as cationic photocatalysts are frequently employed to access the most oxidizing excited-state species, we aimed to demonstrate that charged chromophores such as acridiniums could be incorporated through post-polymerization alkylation. The polymer 1-Acr-Me was synthesized in high yield and found to be an extraordinarily active heterogeneous photocatalyst, promoting the direct acylation of aniline at nearly an order-of-magnitude reduced acridinium loading compared to previously reported homogenous reactions45.

Collectively, our findings imply that a broad scope of photocatalytic chromophores, from common to yet-undiscovered, could be integrated by copolymerization into the rigid structural framework of 1. As the scaffold consistently bestows high specific surface area, excellent film properties, and processability in select non-polar solvents, the described method may constitute a general strategy for the covalent heterogenization of catalysts into porous materials for efficient and economical organic synthesis. In particular, we anticipate that these porous-polymer films, in the role of photocatalytic stationary phases in continuous flow, could represent an enabling technology for large-scale chemical manufacturing.

Methods

Example photocatalytic reaction: synthesis of methyl phenyl sulfoxide (3a)

A dry 20 mL scintillation vial, equipped with a magnetic stir bar, was charged sequentially with 1-PDI (1.34 mg, 0.18 μmol, 0.018 mol% PDI), methanol (4.0 mL), and methyl phenyl sulfide (124.2 mg, 1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The vial was submerged into an ultrasonic bath for 1 min to disperse the catalyst. The vial was capped with a screw cap containing a rubber septum, which was punctured with two 18-gauge needles to vent the reaction mixture to the atmosphere. The cloudy red suspension was stirred vigorously at rt under illumination from a 450 nm blue LED lamp for 6 h. At this point, both the irradiation and the stirring were stopped, and the catalyst allowed to settle for 30 min. Additional methanol (1.0 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a short plug of Celite, washing with methanol (5.0 mL). The filtrate was concentrated with the aid of a rotary evaporator, and the title compound was obtained as a clear oil (133.1 mg, 95% yield) after column chromatography on silica gel, using DCM as the eluent. The catalytic polymer 1-PDI could be recovered from the Celite by washing with THF (10 mL). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.67–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.55–7.47 (m, 3H), 2.72 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.9, 131.1, 129.5, 123.6, 44.1. The spectral data agreed closely with those reported in the literature46.

Data availability

Additional experimental methods and data are available in the Supplementary Information of this paper.

References

McAtee, R. C., McClain, E. J. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Illuminating photoredox catalysis. Trends Chem. 1, 111–125 (2019).

Shaw, M. H., Twilton, J. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Photoredox catalysis in organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 81, 6898–6926 (2016).

Romero, N. A. & Nicewicz, D. A. Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10075–10166 (2016).

Schultz, D. M. & Yoon, T. P. Solar synthesis: prospects in visible light photocatalysis. Science 343, 1239176 (2014).

Prier, C. K., Rankic, D. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 113, 5322–5363 (2013).

Friedmann, D., Hakki, A., Kim, H., Choi, W. & Bahnemann, D. Heterogeneous photocatalytic organic synthesis: state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Green. Chem. 18, 5391–5411 (2016).

Pitre, S. P., Overman, L. E. Strategic use of visible-light photoredox catalysis in natural product synthesis. Chem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00247 (2021).

Twilton, J. et al. The merger of transition metal and photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0052 (2017).

Lang, X., Zhao, J. & Chen, X. Cooperative photoredox catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3026–3038 (2016).

Skubi, K. L., Blum, T. R. & Yoon, T. P. Dual catalysis strategies in photochemical synthesis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10035–10074 (2016).

Gisbertz, S. & Pieber, B. Heterogeneous photocatalysis in organic synthesis. ChemPhotoChem 4, 456–475 (2020).

Le, C. et al. A general small-scale reactor to enable standardization and acceleration of photocatalytic reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 647–653 (2017).

Cambié, D., Bottecchia, C., Straathof, N. J. W., Hessel, V. & Noel, T. Application of continuous-flow photochemistry in organic synthesis, material science, and water treatment. Chem. Rev. 116, 10276–10341 (2016).

Harper, K. C., Moschetta, E. G., Bordawekar, S. V. & Wittenberger, S. J. A laser driven flow chemistry platform for scaling photochemical reactions with visible light. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 109–115 (2019).

Buglioni, L., Raymenants, F., Slattery, A., Zondag, S. D. A., Noël, T. Technological innovations in photochemistry for organic synthesis: flow chemistry, high-throughput experimentation, scale-up, and photoelectrochemistry. Chem. Rev.https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00332 (2021).

Kisch, H. Semiconductor photocatalysis—mechanistic and synthetic aspects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 812–847 (2013).

Ghosh, I. et al. Organic semiconductor photocatalyst can bifunctionalize arenes and heteroarenes. Science 365, 360–366 (2019).

Zeng, L., Guo, X., He, C. & Duan, C. Metal−organic frameworks: versatile materials for heterogeneous photocatalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 7935–7947 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Covalent organic framework photocatalysts: structures and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4135–4165 (2020).

Zhang, W. et al. Visible light-driven C-3 functionalization of indoles over conjugated microporous polymers. ACS Catal. 8, 8084–8091 (2018).

Mak, C. H. et al. Heterogenization of homogeneous photocatalysts utilizing synthetic and natural support materials. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 4454–4504 (2021).

Guo, S. & Swager, T. M. Versatile porous poly(arylene ether)s via Pd-catalyzed C–O polycondensation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11828–11835 (2021).

Swager, T. M. Iptycenes in the design of performance polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1181–1189 (2008).

Long, T. M. & Swager, T. M. Molecular design of free volume as a route to low-κ dielectric materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 14113–14119 (2003).

Long, T. M. & Swager, T. M. Using “internal free volume” to increase chromophore alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17976–17977 (2002).

Lessard, J. J. et al. Self-catalyzing photoredox polymerization for recyclable polymer catalysts. Polym. Chem. 12, 2205–2209 (2021).

Smith, J. D. et al. Organopolymer with dual chromophores and fast charge-transfer properties for sustainable photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 1837 (2019).

Rosso, C., Filippini, G. & Prato, M. Use of perylene diimides in synthetic photochemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 8, 1193–1200 (2021).

Liu, H., Shen, L., Cao, Z. & Li, X. Covalently linked perylenetetracarboxylic diimide dimers and trimers with rigid “J-type” aggregation structure. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 16399–16406 (2014).

Ghosh, I., Ghosh, T., Bardagi, J. I. & König, B. Reduction of aryl halides by consecutive visible light-induced electron transfer processes. Science 346, 725–728 (2014).

Gao, Y. et al. Visible-light photocatalytic aerobic oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides with a perylene diimide photocatalyst. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 7144–7149 (2019).

Rosso, C., Filippini, G., Cozzi, P. G., Gualandi, A. & Prato, M. Highly performing iodoperfluoroalkylation of alkenes triggered by the photochemical activity of perylene diimides. ChemPhotoChem 3, 193–197 (2019).

Weiser, M., Hermann, S., Penner, A. & Wagenknecht, H.-A. Photocatalytic nucleophilic addition of alcohols to styrenes in Markovnikov and anti-Markovnikov orientation. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 11, 568–575 (2015).

Cui, L. et al. Metal-Free direct C–H perfluoroalkylation of arenes and heteroarenes using a photoredox organocatalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 2203–2007 (2013).

Meyer, A. U., Slanina, T., Yao, C.-J. & König, B. Metal-free perfluoroarylation of visible light photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 369–375 (2016).

Lee, J.-W. et al. Organotextile catalysis. Science 341, 1225–1229 (2013).

Baumann, M., Moody, T. S., Smyth, M. & Wharry, S. A perspective on continuous flow chemistry in the pharmaceutical industry. Org. Process Res. Dev. 24, 1802–1813 (2020).

Adamo, A. et al. On-demand continuous-flow production of pharmaceuticals in a compact, reconfigurable system. Science 352, 61–67 (2016).

Williams, J. D. & Kappe, C. O. Recent advances toward sustainable flow photochemistry. Curr. Op. Green. Sustain. Chem. 25, 100351 (2020).

Yang, A. et al. Heterogeneous photoredox flow chemistry for the scalable organosynthesis of fine chemicals. Nat. Commun. 11, 1239 (2020).

Miyake, G. M. & Thierot, J. C. Perylene as an organic photocatalyst for the radical polymerization of functionalized vinyl monomers through oxidative quenching with alkyl bromides and visible light. Macromolecules 47, 8255–8261 (2014).

Dadashi-Silab, S. et al. Conjugated cross-linked phenothiazines as green or red light heterogeneous photocatalysts for copper-catalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 9630–9638 (2021).

Till, N. A., Tian, L., Dong, Z., Scholes, G. D. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Mechanistic analysis of metallaphotoredox C–N coupling: photocatalysis initiates and perpetuates Ni(I)/Ni(III) coupling activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15830–15841 (2020).

Corcoran, E. B. et al. Aryl amination using ligand-free Ni(II) salts and photoredox catalysis. Science 353, 279–283 (2016).

Song, W., Dong, K. & Li, M. Visible light-induced amide bond formation. Org. Lett. 22, 371–375 (2020).

Danahy, K. E., Styduhar, E. D., Fodness, A. M., Heckman, L. M. & Jamison, T. F. On-demand generation and use in continuous synthesis of the ambiphilic nitrogen source chloramine. Org. Lett. 22, 8392–8395 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation DMR-1809740 (T.M.S.) and the KAUST sensor project REP-2719 (T.M.S.). R.Y.L. is funded in part by US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center in Natick, MA. The textile symbol in Fig. 1 has been adapted with permission from Flaticon.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Y.L., S.G., and T.M.S. designed and planned the main experiments. S.G. synthesized and characterized the polymers. S.-X.L.L. carried out XPS studies and assisted with photoconductivity measurements. R.Y.L. performed photophysical characterization, catalytic studies, and other experiments. R.Y.L, S.G., and T.M.S. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors (R.Y.L., S.G., and T.M.S.) declare the following competing interests: a patent has been filed covering the materials and methods reported herein. All of the authors declare no other competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R.Y., Guo, S., Luo, SX.L. et al. Solution-processable microporous polymer platform for heterogenization of diverse photoredox catalysts. Nat Commun 13, 2775 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29811-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29811-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.