In June 1922, the opening battle of Ireland’s civil war destroyed one of Europe’s great archives in a historic calamity that reduced seven centuries of documents and manuscripts to ash and dust.

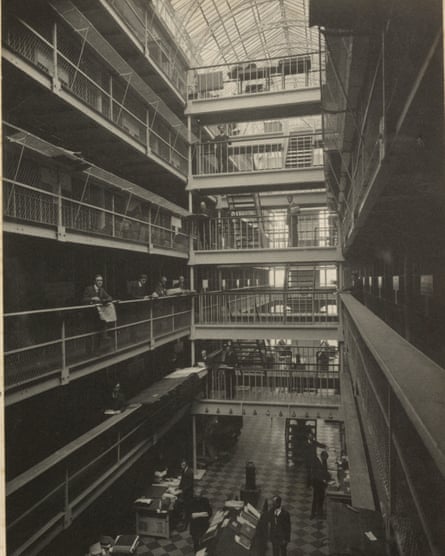

Once the envy of scholars around the world, the Public Record Office at the Four Courts in Dublin, was a repository of documents dating from medieval times, and packed into a six-storey building by the River Liffey. It was obliterated when troops of the fledgling Irish state bombarded former comrades who were hunkered down at the site as part of a rebellion by hardline republicans against peace with Britain.

Each side blamed the other for the destruction, but there was no disputing the consequences. “At one blow, the records of centuries have passed into oblivion,” said Herbert Wood, deputy keeper of the public records. The ruins stood as a testament to loss and a harbinger of the destruction of European cultural treasures in 20th century wars.

Now, on the eve of the disaster’s centenary, a virtual reconstruction of the building and its archives is to be unveiled. Historians, archivists and computer scientists have spent five years piecing together much of what had been thought lost for ever.

“When we began the project, the story was that everything had been lost. But it turns out we have been able to recover hundreds of thousands of documents,” said Peter Crooks, director of Beyond 2022: Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland. “We could not have known the scale of the materials that were out there.”

Retrieved material includes details about the Cromwellian land redistributions that shaped modern Ireland.

The project mixed old-fashioned academic sleuthing, artificial intelligence and collaboration with dozens of archives in the UK, continental Europe, the US and Australia. The results – an immersive 3D reconstruction of the destroyed building and a vast digital archive – will be formally launched on 27 June. It will be an open-access free resource with a searchable website. The 3D reconstruction gives viewers a detailed, and eerie, tour of the Public Record Office as it looked before the fire.

It is hoped the initiative will encourage other attempts to retrieve damaged cultural legacies, such as Notre Dame Cathedral and theatres in Ukraine. “We explored the theme of cultural loss and recovery across the centuries, from the destruction of the Library of Alexandria in antiquity to contemporary acts of cultural loss and destruction, and the ongoing vulnerability of digital archives,” said Crooks.

The project was funded by Ireland’s department of culture, and spearheaded by Crooks and his colleague at Trinity College Dublin’s history department, Ciarán Wallace. It fused AI handwriting transcription with material uncovered in the national archives of Ireland and the UK, the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, the Irish Manuscripts Commission and dozens more institutions.

One strand focused on tens of thousands of “salved” documents – about a twentieth of the archive that survived the flames and had been packed away in boxes. “You could smell the ash when you opened some of them,” said Wallace. Computers were used to decipher centuries-old handwriting, facilitating digitisation.

Another strand saw historians embedded in foreign archives with Irish material to trawl for duplicates and copies of lost documents. They found hundreds of thousands.

Britain’s National Archives in Kew were a trove, thanks to meticulous record-keeping dating from medieval times. Plantagenet monarchs suspected corruption in their Irish colony so copies of audits, inventories and expenditure were stored in London.

In the 19th century, US institutions went on spending sprees at auctions to amass ancient manuscripts, some copied from Dublin. The Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, though created after 1922, gathered correspondence and other documents from private collections that mirrored the doomed archive.

“This is the great revelation – once you start asking: ‘What do you have?’ it can be overwhelming,” said Crooks. In many cases material had been forgotten and undisturbed for decades, curators unaware that they possessed the only surviving copies. In some categories dubbed “gold seams” up to 80% of lost material has been retrieved. In others, such as the pre-famine census, it is zero. It is unclear how much overall has been retrieved but the Trinity historians expect the project to continue filling gaps. “There is so much more out there: we’re just scratching the surface,” said Wallace.

It was once said that the most depressing book in Ireland was a guide to the Public Record Office published in 1919, a catalogue of the treasures lost to the flames. With some treasures recovered and, apparently, more to come, the guide may no longer feel quite so melancholy.