'Poison Pills' Are No Longer Allowed in NFL Contracts—Here's Why

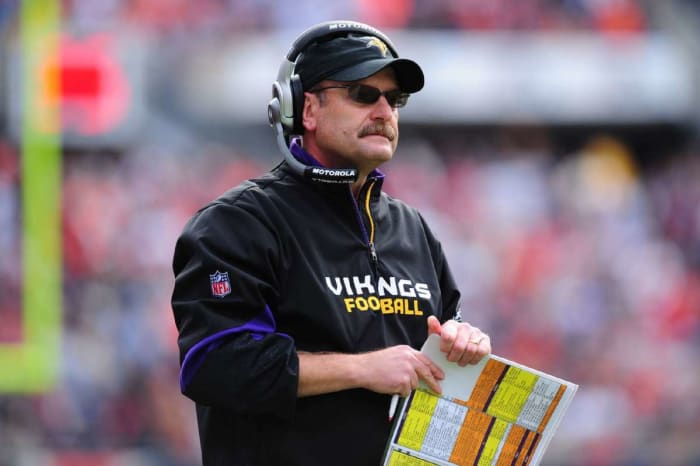

The football coach saw the headlines and made the connection instantly. How could he not? The same phrase being splashed across the front pages of newspapers across the nation had once been applied to him (Brad Childress), his team (the Vikings) and the NFL.

This phrase marked an odd and unexpected connection between a gridiron lifer and Elon Musk, the billionaire entrepreneur, SpaceX founder and Tesla czar. In April, Musk announced his intention to buy Twitter, the social media platform that at first resisted his $43 billion–$44 billion offer. Shortly after, the company deployed an unusual technique, one of few available defenses, by announcing it planned to invoke what’s called a “poison pill” to disincentivize Musk’s pursuit. The phrase stopped Childress, made him chuckle and transported him back 16 years.

In the case of Musk’s bid and Twitter’s early attempts to thwart it, this particular poison pill was more formally labeled a “shareholder rights plan” that’s sometimes designed by corporate boards to guard against losing control to outside interests. If the sale moved forward, Twitter could increase the total shares of its stock. If Musk managed to secure more than 15% of the shares outstanding, other stakeholders would be able to buy more of their own at a steep discount, decreasing the percentage of his stake, or, more ideally, elevating the price tag to a prohibitive perch.

Whoa, thought Childress, who coached for more than four decades until retiring in 2019 and thought he had seen it all until that ’06 offseason. He and the billionaire provocateur had something in common. His mind drifted back to a modest sports controversy involving the NFL’s first “poison pill”—one of two ever invoked.

Childress was at the center of the NFL's first, and only, poison pill contract scandal.

John Biever/Sports Illustrated

It all started in February 2006, shortly after the Seahawks lost to the Steelers in Super Bowl XL. Seattle’s coach, Mike Holmgren, needed to attend to league business, part of his duties as a member of the Competition Committee. But before he left, he made his thoughts on one piece of Seahawks business clear.

Holmgren knew that during the previous offseason the Seahawks had signed their future Hall of Fame left tackle Walter Jones to a seven-year, $50 million extension. And Holmgren knew that the front office had, that same spring, told its future Hall of Fame guard Steve Hutchinson that it wanted to renegotiate with him after the NFL draft. They never did reach an agreement, but the linemates helped the Seahawks form perhaps the most formidable offense to that point in franchise history. In that 2005 season, running back Shaun Alexander set the NFL’s single-season touchdown record and won league MVP honors. And while Seattle lost that Super Bowl held in snowy Detroit, the outcome was controversial, the game close.

Before Holmgren departed he sat down with general manager Tim Ruskell and contract expert Mike Reinfeldt and made it clear that Hutchinson was their priority, the key to another run and a different outcome. If they couldn’t agree on a new contract, they would use the franchise tag on him. The coach also met with Hutchinson, informing his burly, bearded guard of the same directive and reminding the player everyone called Hutch that, either way, he stood to make a lot of money. “O.K.,” Hutchinson responded.

“That was the last conversation I had with him before I got the news,” Holmgren says.

After failing to reach an agreement with Hutchinson the previous offseason, the Seahawks were still unable to agree to terms that February. But instead of slapping the guard with the franchise tag, as Holmgren expected and demanded, they chose to utilize the lesser-known “transition tag” instead.

That decision would prove fatal soon enough. The franchise tag all but guarantees another year of service, because the compensation to acquire a player tagged that way is two first-round draft picks, more than any reasonable general manager would want to pay. The transition tag, in comparison, allows players to meet with other interested teams who can make contract offers, which their franchise has one week to match. The distinction would be critical, setting everything else in motion. The Seahawks saved about $600,000. But they also cracked open a door Holmgren believed he had slammed shut.

When the Vikings called Hutchinson’s agent, Tom Condon, they were surprised to learn that Hutchinson wasn’t opposed to meeting with them. He didn’t want to leave Seattle, but he wasn’t exactly overjoyed with the length of negotiations or the cheaper choice of tags. “Steve was a little pissed they didn’t put the franchise tag on him,” Childress says.

Childress considers Minnesota’s salary-cap guru, Rob Brzezinski, one of the most creative, innovative and capable contract architects in pro sports. He compiled detailed spreadsheets, full of projections and various scenarios—like what a player costs to cut versus what a player costs to stay—that were simplified so coaches could understand how one deal related to every other one.

When it came to Hutchinson, Brzezinski, who politely declined to comment for this article, had an idea. When Childress first heard the twist, it sounded like pure artistry. If Hutchinson agreed, the Vikings would include an unforeseen clause in their offer, one that would effectively make it impossible or at least too expensive for the Seahawks to match.

The offer: seven seasons for $49 million. The clause, which doubled as the catch: if another offensive lineman made more than Hutchinson in any one season, the entire deal would be guaranteed. And since they’d used the transition tag on Hutchinson, Seattle had to choose to either match the Vikings’ contract word-for-word or let their man walk. This presented a problem for the Seahawks, who had just signed Jones to that massive extension and had paid Hutchinson just over $3.5 million the year before. So, if they chose to match, Hutchinson’s salary would eventually be lower than what Jones made, guaranteeing the offer and making it expensive, if not prohibitive. Worse yet: Hutchinson and his representatives agreed to Minnesota’s offer.

Before the clock on the one week Seattle had to match started ticking, Holmgren received an ominous warning at his meetings. It was delivered by John Clayton, the late and perpetually informed NFL scribe. When they bumped into each other in a hallway, Clayton said, “You’re trading Hutchinson.” Holmgren laughed, signaling no way, telling Clayton that when he left not even 24 hours earlier, the plan to slap the franchise tag on Hutchinson was firmly in place.

“Mike,” Clayton said, “I don’t think so.”

The truth would be revealed later the same day, and the irony—discovering the Seahawks had been duped by an unprecedented and, in his mind, unsporting loophole while at meetings for the Competition Committee—was not lost on Holmgren. He found out when Reinfeldt called, interrupting a drink Holmgren was having with his agent—and Childress’s!—and Reinfeldt’s!—in his hotel suite.

Thus began something like the five stages of grief.

“How could this happen?” he asked, working through the initial shock.

“It can’t happen,” he said, falling into denial. “Right?”

Reality started to sink in. It not only could; in all likelihood, it would.

Holmgren has a softer side, a gentle, grandfatherly nature grounded in genuine love for anyone in his orbit. But he also possessed an infamous temper that could erupt at any time, without warning, and did, right then, in front of his agent, Bob LaMonte. His fury seemed to winnow as he ruled out who to be furious at. The members of his front office were simply doing their jobs, and while he doesn’t think they did them well in that instance, he also understands that matching the contract would have been unusual, perhaps even unprecedented. He considered what the Vikings had done duplicitous, a workaround, something that would infuriate most of the league—and surely delight his greatest rivals. That left only Hutchinson, his guy, now a traitor of the worst sort. “Shame on me,” he says of that thought now.

When Holmgren and LaMonte arrived at their scheduled dinner, the coach ordered a stiff drink.

He had no idea that a small-but-significant and infinitely strange slice of NFL history had been set in motion. He felt, well, poisoned. He fumed, in the way that only he could, his facing turning more and more red, eyes narrowing, stress levels heightening.

Soon, he demanded to know why? Ruskell and Reinfeldt explained their rationale—you can’t pay a guard that much—and he reacted with an “Oh, boy.” He begged them to match the offer anyway. They refused. He took a call from the team’s owner, the late Paul Allen, and decided in the moment to accept all blame rather than cast it toward the decision-makers.

That same week, Childress sat up straight when his secretary announced, “Mike Holmgren is on the line for you.” He pictured the volcano that was Holmgren’s fury and braced for an eruption. But Holmgren, on that day, was remarkably calm. He started out with, “I’m trying to be a good friend” and “I’ve always respected you.” Then he told Childress that the Competition Committee generally frowned on that type of deal. They hadn’t outlawed poison pills, but they could, and might, and perhaps the contract wouldn’t be approved. Childress understood that he and the Vikings held all the leverage. He wanted a tough guard, a staple, like Jon Runyan was to Philadelphia when he worked on the Eagles staff. Yes, he was a rookie head coach. But he wasn’t about to be pushed into a career-altering mistake before he won or lost his first game in charge. He told Holmgren that there was nothing he could do. Seattle had those seven days to match—the coach-to-coach equivalent of sorry, not sorry.

Mike Holmgren had an infamous temper that could erupt at any time.

Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated

After returning to Seattle, while at Seahawks headquarters on a random afternoon, Holmgren heard that Hutchinson was in the building. He wanted to meet with the player who had spurned him, and he did, that day, in the office of longtime equipment manager Erik Kennedy, who closed the blinds. Kennedy didn’t need to see the conversation to understand the tenor. He heard yelling and cursing and the sound of fists banging into tables. “I just went off, you know,” Holmgren admits.

Still smoldering, he followed that with another phone call to Childress. Holmgren said the Seahawks planned to make a run at Nate Burleson, a talented wideout and restricted free agent for the Vikings. Childress said the Vikings might entertain a trade for a first-round draft pick. “You’re not getting my one,” Holmgren spit back. “And you’re not going to be able to match the contract”—a right of teams with restricted FAs.

“I don’t want to do it,” Holmgren added. “But the guys next door, the front office, they are going to write it.”

Which, of course, they did. Seattle’s offer contained multiple poison pills that spoke nakedly to its main aim: revenge. One clause stated that Burleson’s deal would be guaranteed in full if he played more than five games in any one season in Minnesota. Even if the Vikings wanted to match the offer, they could not, and what had started as a workaround had morphed into something bigger, more spiteful; Holmgren’s revenge served not cold but hot.

Minnesota ultimately ended up on the better end of the exchange. Burleson compiled an average of 439.5 receiving yards in four seasons as a Seahawk. Hutchinson made the Pro Bowl in his first four seasons with the Vikings, remained perhaps pro football’s most dominant guard and reset the market at his position. Essentially, he was exactly the kind of player who would force a historic moment—so elite that a team that coveted him would go to great lengths to obtain his services and so valued that the team that lost him would create its own transaction in response out of no more than hurt feelings.

Other NFL owners dressed down the Vikings contingent at the next owners meetings, according to a source who was there but didn’t run either of the involved teams. One, Patriots owner Robert Kraft, laughed at the Minnesota coaches for their “crazy overpayment” of a guard. Not long after, in 2011, New England signed its star guard, Logan Mankins, to an even richer contract.

In Seattle, an era effectively ended after Hutchinson departed. An average of $7 million per season for a player of Hutchinson’s caliber seems like a downright bargain now in hindsight. The Seahawks whiffed on luring Kris Dielman to town, then signed Mike Wahle, a move they later regretted after Wahle retired from chronic injuries to his shoulders. Seattle did make the playoffs the next two seasons, but they were never again a true contender under Holmgren.

The Vikings, even with Hutchinson, didn’t make the playoffs in his first two seasons after the poison pill ordeal. But in 2010 they advanced to the conference championship game, under Childress and with Hutchinson plowing interior defensive linemen.

Before all of that, though, league officials who fashion the NFL’s schedule added a juicy twist to the 2006 season. Minnesota would fly to Seattle and play the team it had just outwitted on Oct. 22. The crowd, once home, now away, booed Hutchinson loudly every time his offense had the ball. He had just played in the Super Bowl for them! Only seven months earlier!

The Vikings won that afternoon, blowing out the Seahawks behind Hutchinson, who split open Seattle’s defense for a 95-yard Chester Taylor touchdown run, the longest in franchise history at that point. When Hutchinson tried to speak to his spurned coach afterward, Holmgren turned his back and walked right past him.

Holmgren, looking back, says the poison pill “may have cost us a Super Bowl.” He adds, “It should not have happened.” What hurt most, what hurt for a long time, was that Hutchinson never called him. He would have flown home, “made it happen, somehow.”

The tit-for-tat led to an NFL rule change that’s now applicable to every restricted free agent and every player slapped with the transition tag. The Hutchinson Rule, some called it. The relevant language states, “No Offer Sheet may contain a Principal Term that would create rights or obligations for the Old Club that differ in any way (including but not limited to the amount of compensation that would be paid, the circumstances in which compensation would be guaranteed, or the circumstances in which other contractual rights would or would not vest) from the rights or obligations that such Principal Term would create for the Club extending the Offer Sheet (i.e., no ‘poison pills’).”

Imagine how different the NFL might look now, on every team, with every roster, had league officials allowed poison pills to remain an effective tactic. Imagine what cap wizards like Brzezinski might have come up with.

Hutchinson had two All-Pro seasons with Seattle, and after moving to Minnesota, he had three more.

Kirby Lee/Getty Images

Hutchinson retired in 2012, after 12 NFL seasons spent playing for three franchises. He made All-Pro in seven of those seasons (in five, he was named to the first team). But that’s not, perhaps, his most memorable place in professional football history.

Kennedy, who’s still in Seattle and now the director of equipment for the Seahawks, invited both Holmgren and Hutchinson to his wedding, almost a decade after the saga that connected them unfolded. This marked the first time in years that both had been in the same room. Again, Holmgren walked right by the player who helped him reach that Super Bowl with Seattle. Only this time, Holmgren’s wife, Kathy, hit him with an, “Oh, please,” as she implored her husband to patch things up. They did.

In 2015, Hutchinson told Holmgren that he wanted to look into coaching, and Holmgren added Hutch to his staff at the NFL Collegiate Bowl that year and in the next one. Old, deep wounds continued healing. Hutchinson drove his old coach to practices and shadowed Holmgren’s routines. Both men eventually decided: Football was an emotional endeavor, but elements of it would always remain outside their full control.

At the owner’s meetings one year, LaMonte invited Holmgren and Childress to the same dinner. They kept it pleasant and tried to avoid any sort of meet-up, only to end up seated right across from each other. The meal unfolded without incident, the tone affable, if not a full embrace.

In 2020, Hutchinson went into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Holmgren attended and took all his Seahawks out to dinner, where they roasted him, his eruptions and his reaction to the contract that changed NFL history. He still spends much of his year in the greater Seattle area, where he and Kathy keep a home that’s only a short drive from the Seahawks’ old facility. Oddly enough, Hutchinson returned as well. He decided not to coach but accepted a smaller opportunity to evaluate draft prospects for Seattle’s current front office. Of all teams. In all places.

In the last year or two, the men who once stood at the center of a scandal have actually met in Kennedy’s office on a few, informal occasions. Those times, no one screamed or slammed their fists. They simply laughed at how everything in the NFL connects, in one way or another, even to a Twitter takeover by a billionaire who now understands what they learned 17 years ago: So-called poison pills received the most accurate of names.

More NFL Coverage: