Abstract

The primary Antarctic contribution to modern sea-level rise is glacial discharge from the Amundsen Sea sector of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The main processes responsible for ice mass loss include: (1) ocean-driven melting of ice shelves by upwelling of warm water onto the continental shelf; and (2) atmospheric-driven surface melting of glaciers along the Antarctic coast. Understanding the relative influence of these processes on glacial stability is imperative to predicting sea-level rise. Employing a beryllium isotope-based reconstruction of ice-shelf history, we demonstrate that glaciers flowing into the Amundsen Sea Embayment underwent melting and retreat between 9 and 6 thousand years ago. Despite warm ocean water influence, this melting event was mainly forced by atmospheric circulation changes over continental West Antarctica, linked via a Rossby wave train to tropical Pacific Ocean warming. This millennial-scale glacial history may be used to validate contemporary ice-sheet models and improve sea-level projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing ice loss and sea-level contribution from Antarctica since the early twenty-first century is caused by rapid thinning, retreat, and acceleration of major outlet glaciers of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS)1. Recent WAIS mass loss has been focused within the Amundsen Sea Embayment (ASE), which may indicate the beginning of marine ice sheet instability2,3. Ice mass loss since the 1990s is attributed to the ocean-driven melting of ice shelves by the upwelling of relatively warm Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) onto the West Antarctic continental shelf1,4. Precipitation and warming over West Antarctica was also more elevated in the 1990s than at any time over the last 200 years, linked to higher tropical Pacific Ocean temperatures5,6. Atmospheric rivers (narrow bands with enhanced water vapour flux) associated with this tropical-polar teleconnection represent 100% of summer surface melt in Marie Byrd Land7, presenting an additional contribution to global sea-level rise from the atmospheric-driven melting of glaciers along the West Antarctic coast. Significant uncertainty therefore remains for the permanence of increasing ice loss, projected contributions to sea level, and the dominant driving mechanisms behind mass balance change1. Integrated models predicting the timing and rate of future Antarctic ice mass loss rely on validation from long-term (102–103 yr) records of past ice-sheet change8,9, and therefore require glacial reconstructions since the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)10.

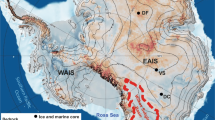

Marine records from the ASE reveal that the Amundsen sector of the WAIS (Fig. 1a) reached its modern limits by the Early Holocene11 (Fig. 1b), driven by upwelling CDW onto the continental shelf due to a southerly position of the Southern Hemisphere westerly wind belt12. However, the mechanism behind subsequent early-to-mid-Holocene thinning of ice streams surrounding the ASE13,14 is still not well understood15. Here we apply beryllium (Be) isotopes, a proxy for glacial processes, to provide a 10.3 kyr history of the Cosgrove Ice Shelf (CIS) in the eastern ASE (Fig. 1b). We measured the reactive 10Be abundance ([10Be]reactive), 9Be abundance ([9Be]reactive) and 10Be/9Be ratios in marine sediments collected during the IB Oden Southern Ocean cruise (OSO-0910)16 (“Methods”). Kasten cores KC-15, KC-16 and KC-17 were collected just offshore the modern terminus of the CIS in Ferrero Bay (Fig. 1c). Beryllium isotope records are supported by published multi-proxy analysis of total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), microfossil abundance and assemblages (diatoms and foraminifera), and magnetic susceptibility (MS), which together provide a record of Holocene productivity and grounding line retreat17. Beryllium isotope records from KC-15 are compiled onto a new age-depth model (Fig. S1) to elucidate the timing of CIS retreat during the Holocene.

a Map of Antarctica displaying a generalised position of Antarctic Circumpolar Current-Circumpolar Deep Water (ACC-CSW) and Weddell Sea Transitional Water (WSTW). b Ice velocity64,65, satellite imagery66, radiocarbon dates and terrestrial cosmogenic nuclide dates11,13,14,48 for the Amundsen Sea Embayment, Pine Island Trough (PIT), and Pine Island Bay (PIB). c Location of OSO-0910 KC-15, KC-16, and KC-17 in Ferrero Bay with multibeam swath bathymetry16. Maps were constructed using Quantarctica from the Norwegian Polar Institute67.

Results and discussion

The [10Be]reactive, [9Be]reactive, and 10Be/9Be ratios recorded for KC-15, KC-16, and KC-17 are presented in Fig. 2. Cores KC-15 and KC-17 display four key features: (1) from the base of the cores to ~111 cm below the seafloor (cmbsf), the [10Be]reactive, [9Be]reactive, 10Be/9Be, TOC, TN, and diatom abundance are relatively low, while MS and the abundance of the calcareous planktic foraminifera, Neogloboquadrina pachyderma, are relatively high (Fig. 2a, c); (2) between ~111 and ~71 cmbsf, [10Be]reactive, 10Be/9Be, TOC, and TN increases, diatom abundance remains low, MS decreases, and N. pachyderma becomes absent. Reactive 9Be also increases between ~111 and ~71 cmbsf in KC-17 (Fig. 2c) yet plateaus in KC-15 above ~101 cmbsf (Fig. 2a); (3) between ~71 and ~31 cmbsf, [10Be]reactive, [9Be]reactive, 10Be/9Be, TOC, TN, and MS remain relatively constant while the presence of the benthic foraminifera, Bulimina aculeata, is observed in KC-15 (Fig. 2a, c); (4) above ~31 cmbsf, TOC, TN, and diatom abundance increases and MS gradually declines (Fig. 2).

a–c The reactive 9Be abundance, 10Be abundance, and 10Be/9Be ratios (this study), alongside total nitrogen (TN), total organic carbon (TOC), diatom abundance, foraminifera taxa (counts per gram of dried sediment, gds), magnetic susceptibility (MS), and lithological descriptions17 of OSO-0910 KC-15 (a), KC-16 (b), and KC-17 (c).

The strong correlation between [10Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be ratios in all three cores (Tables S3–S5) suggests the rise in [10Be]reactive is largely controlling variation in the 10Be/9Be ratios. Reactive 10Be, and therefore 10Be/9Be, displays a similar trend to TOC and TN in KC-15, KC-16, and KC-17 (Tables S3–S5). Magnetic susceptibility records a negative correlation to Be isotopes (Tables S3–S5), representing a lithologic transition from coarse-grained sediments with high sand content (% sand = 14–46%) at the base of the core to overlying fine-grained sediments that are rich in silt and clay17. Diatom abundance correlates with Be isotopes in KC-15 and KC-17, with the exception of [9Be]reactive in KC-17, however, diatoms were not counted at the same sampling interval making a direct comparison with Be concentration difficult (Tables S3, S5).

The sediments from KC-15 record the last ~10.3 kyr of glacial history for Ferrero Bay and the CIS. According to our new age model (Fig. S1; Table S1), Be isotope data reveal three periods of interest (Fig. 3a): (1) in the Early Holocene, between ~10.3 and ~9.8 kyr BP, the 10Be/9Be ratios are low at ~0.42; (2) transitioning from the Early Holocene to Mid-Holocene, 10Be/9Be increases between ~9.8 kyr BP and ~5.9 kyr BP from ~0.46 to ~2.33; (3) then through the Late Holocene, 10Be/9Be ratios are relatively constant at ~2.3. During the Late Holocene, 10Be, 9Be, TOC, and TN potentially display millennial-scale variability, increasing after ~1.4 kyr BP (Fig. 2), but higher temporal resolution would be needed to support this notion. In the following section, we discuss the environmental and physical factors that could contribute to Be isotope variation in Ferrero Bay during the Holocene.

The 10Be/9Be ratios (a) and relative 10Be vs. 9Be relationship (b) in OSO-0910 Kasten core KC-15. Error bars represent 2σ confidence intervals (Fig. S1). Relative Be isotope values from offshore Wilkes Land37 and Baffin Bay36 are presented using light blue diamonds and dark blue squares, respectively. The dashed black line, light blue line, and dark blue line represent the relationship for samples from this study, Wilkes Land37, and Baffin Bay36, respectively.

Beryllium isotope systematics in glacial environments

The cosmogenic isotope 10Be is produced by the interaction of cosmic rays with oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere and is deposited to the Earth’s surface via dust or precipitation18, becoming enriched in surface waters under high precipitation such as the equatorial Pacific (~1100 atoms/g)19,20. Beryllium-9, on the other hand, is released during the chemical weathering of silicate minerals18 and is enriched in waters near high fluvial or aeolian inputs e.g., equatorial Atlantic surface waters in proximity to Saharan dust plumes20. Away from regions of high surface inputs, such as the South Pacific, Be follows a general profile of nutrient scavenging with a depletion in the surface mixed layer (~750 atoms/g) and an enrichment in deeper waters (~2000 atoms/g), reflecting the high scavenging potential of Be19,20,21. The 10Be/9Be of Pacific seawater has an average ratio of ~1 × 10−7 but ranges from ~0.4 × 10−7 to ~3.1 × 10−7 in equatorial surface waters of the Atlantic and Pacific due to additional inputs of 9Be and 10Be, respectively20. The disparate sources of 10Be and 9Be led to fluctuations in the 10Be/9Be of seawater, recorded in marine sediments and ferromanganese crusts, over Quaternary climate cycles, due to large regional variability in fluvial inputs between glacial and interglacial periods22.

The Be isotope composition of marine sediments on the continental shelf is controlled by the relative mixing of two reactive phases, one sourced from the coast, defined by low 10Be/9Bereactive due to the input of fluvial 9Be, and another sourced from entraining seawater, defined by high 10Be concentrations and 10Be/9Be ratios23. The high 10Be/9Be of seawater is augmented in polar regions by the input of 10Be from atmospheric sources18,24 and/or the melting of sea ice ([10Be] = ~0.25–0.65 ×104 atoms/g)25 and ice sheets ([10Be] = ~1–3 × 105 atoms/g)26, which act to accumulate meteoric 10Be overs years to millennia, leading to exceptionally high surface water ratios which have been observed in the Deep Canadian Basin (~1.4 × 10−7)25 and Drake Passage (~3.3 × 10−7)19,20, respectively. The export of meltwater signals further offshore may be enhanced by the calving of icebergs and their subsequent passage off the continental shelf27.

The separate transport pathways and sources of 10Be and 9Be in ice sheets has allowed Be in glaciomarine sediments to become a powerful proxy of glacial dynamics24,27,28,29,30,31. Open marine sediments close to the calving line of ice shelves are defined by higher Be concentrations and 10Be/9Be ratios relative to other glacial environments due to efficient scavenging of Be by diatoms from seawater defined by higher overall ratios as previously discussed24,28. Lower 10Be concentrations and 10Be/9Be ratios can be found in sub-ice shelf sediments, induced by lower productivity and limited advection of open marine material into the ice-shelf cavity24,27,28. Finally, sediments in proximity to the grounding line receive 9Be from the basal zone during glacial erosion leading to exceptionally low 10Be/9Be ratios27,31. Here, we relate Be isotope variation in Ferrero Bay to three main processes: (1) environmental setting; (2) depositional processes; and (3) meltwater contribution (Fig. 4).

a Open marine, sub-ice-shelf, and subglacial environments are defined by different geochemical compositions27,34. b Melting of icebergs and sea ice near the calving line releases 10Be which is rapidly scavenged by diatom frustules and organic matter before becoming advected under the ice-shelf with other marine material by ocean currents such as intruding CDW. c Meltwater rich in 10Be is released from the ice-shelf base and scavenged by fine-grained sediment delivered from the grounding line. This figure was modified from Yokoyama et al.24 and White et al.27.

The Cosgrove Ice Shelf in the Holocene

Bathymetric surveys reveal that grounded ice occupied Ferrero Bay during the LGM as part of the larger ice stream in the Cosgrove-Abbot Trough, which reached the continental shelf edge north of the Abbot Ice Shelf11,32,33 (Fig. 1b). The Amundsen Sea Ice Shelf retreated into the Pine Island Trough (PIT) to a position just north of Ferrero Bay by ~13.6 kyr BP, before moving south of Ferrero Bay to ~150 km from the current grounding line of Pine Island Glacier by ~10.6 kyr BP32. The grounded ice sheet within Ferrero Bay retreated landward at a similar time from the mouth of Ferrero Bay at ~13.6 kyr BP32 to the proximal core site of KC-15 by ~11 kyr BP17, maintaining a floating ice shelf that reached the distal core site of KC-1717,33. Based on the updated age model for Ferrero Bay sediment cores, the changes in lithology and magnetic susceptibility in KC-15 (KC-17) indicate two phases of grounding line retreat within Ferrero Bay terminating by 124 (131) and 105 (99) cmbsf, corresponding to ~10.7 kyr BP and ~9.6 kyr BP, respectively17.

Prior to ~9.8 kyr BP (>111 cmbsf in KC-15), low Be concentrations and 10Be/9Be indicate that the KC-15 and KC-17 core sites remained proximal to the grounding line. Subsequently, an increasing trend in [10Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be is observed between ~9.8 kyr BP (~111 cmbsf) and ~5.9 kyr BP (~71 cmbsf) suggesting a gradual retreat of the grounding line and the development of a more distal environmental setting (Figs. 2a, c, 3a and 4a). The grounding line stabilised, and a permanent ice shelf established in Ferrero Bay between ~5.9 kyr BP (~71 cmbsf) and ~2.3 kyr BP (~31 cmbsf), as indicated by relatively constant 10Be/9Be of ~2.1 (Figs. 2a, c, 3a and 4a). Finally, the ice-shelf collapsed and open marine conditions established by ~2.3 kyr BP at the site of KC-17 and ~1.4 kyr BP at the site of KC-15. The progression of glacial retreat and changing environments is supported by a shift from a coarse-grained lithology with low TOC and high MS near the base of the sediment record, to a fine-grained lithology with intermediate TOC and a gradually decreasing MS up-section, and, finally, to TOC values above 0.5% and higher abundance of diatoms and benthic foraminifera, indicating open marine conditions17,34 (Figs. 2 and 4a).

The relative change in Be concentration across these various glacial environments is likely to be controlled by depositional processes such as dilution, scavenging efficiency, and/or extraction efficiency22, much like the percentage of TOC35. From the bottom of the cores to ~111 cmbsf in KC-15 and KC-17, TOC is likely diluted by the input of coarse-grained clastic material from the grounding line with a high sand content of 27–46% (ref. 17). From ~111 cmbsf, TOC is largely controlled by steadily increasing accumulation rates (calculated from the new age-depth model) of fine-grained (% sand ≦ 12.5%) sediment up-section, which allows for a more rapid passage of organic carbon through the near-surface zone, reducing its degradation35. Reactive 10Be, and to a lesser extent 9Be, displays a strong correlation to TOC (Fig. 2; Tables S3–S5), suggesting Be concentration may also be largely controlled by dilution and/or scavenging efficiency. A similar lithological control is observed in Baffin Bay whereby [Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be are relatively low over the last glacial cycle due to the poor scavenging efficiency of coarse-grained carbonate-rich material but Be isotopes increase by over an order of magnitude during ice-surging events associated with the production of fine-grained feldspar-rich glacial flour36. The percentage of TOC and Be concentration in Ferrero Bay sediments may also be related to productivity (i.e., diatom and foraminifera abundance) in the overlying water column or the advection of biogenic material into the ice-shelf cavity. However, the diatoms were not counted at the same sampling interval and other organic plankton such as dinoflagellates are not included in previous studies17, limiting a direct comparison between TOC, Be abundance, and productivity.

Much like Be isotope concentration, the relationship between relative 10Be and relative 9Be is largely controlled by extraction efficiency, scavenging efficiency, and/or dilution, generally defined by a 1:1 relationship. Changes in the gradient of this relationship above or below one is driven by an additional input of 9Be or 10Be, respectively22,37. The relative 10Be vs. relative 9Be relationship of sediments from Baffin Bay and offshore Wilkes Land are defined by a gradient less than one (Fig. 3b) controlled by the additional flux of meltwater-derived 10Be from nearby ice sheets36,37. This leads to higher 10Be/9Be ratios during periods of intense glacial discharge such as Heinrich events36 and Pliocene interglacials37. Sediments from KC-15 to KC-17 display a similar relationship to Baffin Bay and offshore Wilkes Land (Fig. 3b) indicating an additional input of meltwater-derived 10Be to Ferrero Bay may be contributing to the increase in 10Be/9Be ratios from ~9.8 kyr BP to ~5.9 kyr BP (Fig. 3a).

Meltwater input to Ferrero Bay is derived from one of two sources: (1) the calving of ice shelves and melting of icebergs, the meltwater of which is subsequently advected under the CIS (Fig. 4b), or (2) the basal and/or surface melting of the CIS (Fig. 4c). From 10.3 to 9.8 kyr BP, limited productivity of diatoms and calcareous foraminifera resulted from the advection of offshore currents under the Amundsen Sea ice shelf, as evidenced by low benthic productivity and the presence of the planktic foraminifer N. pachyderma, suggesting that ocean currents accessed the grounding line at this time17,33 (Fig. 2a, c). During this period, [10Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be are at their lowest, however—indicating a negligible amount of Be is advected from the calving line or from offshore currents (Fig. 4b).

From 9.8 to 2.3 kyr BP, diatom abundance is low, and calcareous foraminifera and benthic productivity are low but present, indicative of a distal glacio-marine environment and limited advection under the extended paleo-ice shelf17,33 (Fig. 2a, c). During the period, [10Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be increase (Fig. 2a, c), indicating that the majority of Be is not sourced by water flowing from the continental shelf and is more likely associated with subglacial water flowing out from beneath the ice sheet (Fig. 4c). This is supported by observations from Lake Maruwan Oike, East Antarctica, which records peak [10Be]reactive and 10Be/9Be during a brackish transition to lacustrine conditions, implying Be is derived from the melting of local glaciers29. Importantly, a benthic foraminifera species thought to be associated with CDW, B. aculeata, is present at 51 and 71 cmbsf in KC-15 (Fig. 2a), indicating CDW incursion during the Mid-Holocene17, but the advection of this offshore water mass apparently had limited influence over Be isotope values which remain high but relatively constant during this time.

To summarise, Be isotope data from Ferrero Bay suggests the CIS underwent a dramatic shift from the Early-to-Mid-Holocene: (1) the grounding line was proximal to KC-15 prior to ~9.8 kyr BP during the Early Holocene, with a permanent ice-shelf extending beyond KC-17 into the ASE; (2) the grounding line retreated from the Early-to-Mid-Holocene between ~9.8 kyr BP and ~5.9 kyr BP, associated with melting of the CIS and its paleo-ice stream; (3) the grounding line and the CIS remained stable for the rest of the Mid-Holocene until ~2.3 kyr BP; (4) the CIS retreated past KC-15 to its modern position during the Late Holocene, establishing open marine conditions in Ferrero Bay. In the following section, we relate our findings to the wider context of the Amundsen Sea sector of the WAIS and the possible mechanisms driving West Antarctic climatic change during the Holocene.

Atmospheric warming led to Holocene melting

Melting and retreat of the CIS and its paleo-ice stream recorded here corresponds well to a respective ~560 m and ~150 m thinning of the Pope Glacier18 and Pine Island Glacier16 from 9 to 6 cal kyr BP and 8 to 6 cal kyr BP, indicating a widespread melting event within the Amundsen Sea sector of the WAIS (Fig. 5a). Early Holocene deglaciation of PIB is linked to the enhanced upwelling of relatively warm CDW (Fig. 5c) into the ASE12,33 (Fig. 5b). Benthic δ13C data from PIB records a rapid reduction of CDW inflow at 9 kyr BP while planktic δ13C data display a gradual decline between 10.4 and 8 kyr BP (Fig. 5b), associated with a lessening of CDW heat supply12,38 (Fig. 5c). Sediments studied here likely correspond to “Unit 1” and “Facies 3” in cores from PIT33 and PIB32, respectively, representing a switch from proximal glacimarine sediments accessed by warm water flowing onto the continental shelf before ~9.6 kyr BP, as evidenced by the presence of N. pachyderma (Fig. 2a, c)17, to distal meltwater-derived glacimarine sediments, devoid of biogenic material, emanating from beneath the ice sheet by ~7.8 ka BP33. The 10Be/9Be ratios from KC-15 are at their lowest during maximum CDW incursion into the PIB region, increasing after 9 kyr BP (Fig. 5a, b). This suggests that early-to-mid-Holocene retreat of the CIS was generally not associated with the upwelling of CDW into Ferrero Bay, albeit some contribution is constrained to the Mid-Holocene between ~5.9 and ~4 kyr BP as inferred by the presence of the CDW-associated benthic foraminifer B. aculeata17 (Fig. 2a).

a Meltwater discharge from the CIS based on 10Be/9Be ratios from OSO-0910 KC-15 (black line) alongside the thinning history of the Pine Island (light orange triangles) and Pope (dark orange triangles) glaciers derived from exposure ages of samples from Mt. Murphy and Mt. Moses/Maish Nunatak, respectively13,14. b δ13C values of benthic (grey diamonds) and planktic (black diamonds) foraminifera relative to estimated values for the CDW (yellow box) and AASW (blue box) from PS75/160 and PS75/167 (Fig. 1b)12. c Five-point moving average of sea surface temperature (SST) estimated for the Palmer Deep, western Antarctic Peninsula shelf (red line; ODP 1098, Fig. 1a) and Mg/Ca ratios of benthic foraminifera as a semi-quantitative representation of bottom-water temperatures within PIB (black crosses; PS75/160, Fig. 1b)12,38. d Titanium µ-XRF analysis from Emerald Lake on Macquarie Island39 (light green line) and five-point moving average of ice volume corrected Globorotalia inflata δ18O (δ18Oivc) recorded in the South Atlantic40 (dark green line). e Alkenone SST index from the eastern Pacific equatorial cold tongue41 (light yellow line) and mean thermocline water temperature anomaly of the Indo-Pacific warm pool43 (dark yellow line). f Atmospheric temperature68 (light blue line) and accumulation rates46 (dark blue line) for the WAIS Divide core (Fig. 1a). The grey box highlights the interval of 9 to 6 cal kyr BP.

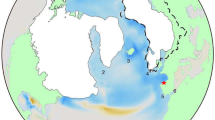

During the Holocene, the Southern Hemisphere westerly winds were at their weakest between 11 and 9 cal kyr BP, gradually intensifying during the Mid-Holocene to maximum values at ~ 5 cal kyr BP39, associated with a poleward migration of the westerly wind belt between 8.5 and 5.5 cal kyr BP40 (Fig. 5d). The southerly shift in the westerly winds coincides with a progressive warming of the tropical Pacific41 (Fig. 5e) and greater thermal contrast across the zone of strong westerlies42. A steeper west to east upper-ocean temperature gradient and intensified Walker circulation in the equatorial Pacific led to a second peak in thermocline warming of the Indo-Pacific warm pool during the Mid-Holocene, reaching peak warming between 7 and 6 cal kyr BP43 (Fig. 5e). Tropical Pacific warming can generate an atmospheric Rossby wave train that influences atmospheric circulation over the Amundsen Sea, leading to advection of warm air onto continental West Antarctica (i.e., Ellsworth Land and Marie Byrd Land), associated with cooling and greater sea-ice formation around the Antarctic Peninsula5, suggesting a link between Pacific warming and ice sheet thinning around the ASE7,44.

A southerly position of the westerly jet and an increase in atmospheric moisture content led to a poleward displacement and a higher frequency of Pacific atmospheric rivers during the Mid-Holocene45. A strengthening of the Amundsen Sea Low increased cyclonic-driven precipitation over continental West Antarctica between 9 and 6 kyr BP, as evidenced by a relatively small surface air temperature warming coupled to a dramatic increase in accumulation rates at the WAIS Divide ice core46 (Fig. 5f). Intense rainfall would have enhanced surface melting over the West Antarctica coast, thus decreasing surface albedo and increasing regional melt, while higher mixed-phase cloud cover would have reduced radiative cooling and therefore meltwater refreezing7,44. Furthermore, if atmospheric rivers travel perpendicular to coastal mountain ranges near the Amundsen Sea, the resulting föhn winds can enhance surface melt through adiabatic warming of descending dry air7.

Surface melting and/or surface-meltwater-enhanced calving of floating ice shelves would trigger rapid ice flow accelerations in outlet glaciers9, leading to retreat of the CIS and meltwater discharge of 10Be, via basal melting or meltwater injection from surface melt ponds and lakes through ice fractures and moulins47, and thinning of ice streams along the Ross and Amundsen Sea coasts13,14,48,49 during the Early-to-Mid-Holocene (Figs. 4c and 5a). Conversely, an ice core from the east Antarctic Peninsula records a cooling trend from 10 to 8 cal kyr BP50, associated with a reduction in glacial discharge51 and greater sea-ice formation52, while sediment core biomarkers suggest surface water cooling38 (Fig. 5c) along the west Antarctic Peninsula between 9 and 6 cal kyr BP. The cooling trend observed along the Antarctic Peninsula at the same time as a warming trend in the ASE is consistent with a teleconnection between tropical Pacific warming and atmospheric circulation over West Antarctica5. Hence, we suggest that higher tropical Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures led to atmospheric warming and higher precipitation over continental West Antarctica, inducing melting and retreat of the CIS and thinning of other glaciers in the ASE between 9 and 6 cal kyr BP.

Outlook and future research

Presently, glaciers flowing into the ASE are the main Antarctic contribution to global sea-level rise, averaging 0.23 ± 0.02 mm yr−1 between 1992 and 2013 (ref. 2,3). The driving mechanism of sea-level rise acceleration has been attributed to ocean-driven melting of ice shelves that buttress glacial flow1,4,12. However, atmospheric rivers associated with tropical-polar teleconnections present a mechanism for substantial contribution to seasonal surface melt over continental West Antarctica as well7. Greater atmospheric moisture content and poleward expansion of the Hadley cells under rising greenhouse gas emissions suggest atmospheric river climatology is already beginning to resemble that of the Mid-Holocene45, possibly linked to extensive melt events along the Ross and Amundsen Sea coasts since the 1990s6,7,44. Our study suggests that future warming and increasing precipitation brought by enhanced atmospheric river activity could contribute to further surface melting and significant glacial discharge into the ASE. This information is vital for validating numerical models, thereby improving future predictions of sea-level rise8,9,53,54 which is currently estimated to be as much as 1 m from Antarctica by the end of the twenty-first century9. Here, we demonstrate that Be isotopes can be successfully employed alongside other sediment and biological proxies to reconstruct past changes in depositional environment, ice shelf extent, and meltwater input—a parameter that is completely missing from most glacial records since the LGM11,27. However, uncertainty remains owing to the multiple sources and processes influencing the Be isotopes systematics of glacimarine sediments27. Future work will need to constrain the Be abundance in sea ice, ice sheets, and shelf waters, whilst also determining how Be is incorporated into sediments from the grounding line to the continental slope.

Methods

Study location and core sampling

Ferrero Bay is located within eastern PIB in the ASE (Fig. 1b), reaching a maximum depth of ~1300 m to the north and an average of ~700 m to the south near the Canisteo Peninsula (Fig. 1c). The King Peninsula separates Ferrero Bay from the Abbot Ice Shelf. Ferrero Bay connects to the continental shelf edge through the eastern trough of the ASE, receiving relatively warm and saline CDW from PIB below ~275 m water depth17. Three Kasten cores were collected from Ferrero Bay during the IB Oden OSO-0910 expedition from 2009 to 2010: KC-15 (73.36° S, 101.84° W; 1274 m water depth), a 1.3 m sediment core from the innermost fjord; KC-16 (73.45° S, 102.08° W; 706 m water depth), a 0.4 m sediment core from a structural high; and, KC-17 (73.42° S, 102.83° W; 855 m water depth), a 1.4 m core recovered from the outer bay (Fig. 1c). All three cores generally consist of clays ranging from clayey sand to greenish-blueish clay (Fig. 2) and record local glacial history, biological productivity, and oceanographic conditions during the Holocene17. KC-15 and KC-17 are divided into four units based on sedimentological, geochemical, and palaeontological properties with KC-16 including only the uppermost unit17.

Beryllium isotope analysis

Reactive Be ([10Be]reactive and [9Be]reactive) was separated from marine sediments using the technique previously presented29. Approximately 0.1 g of sediment was dried and crushed before being leached with 0.04 M hydroxylamine hydrochloride in 25% acetic acid for 7 h at 80 °C. An aliquot of the leached solution was measured for reactive 9Be using a Thermo® ELEMENT XR high resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (HR-ICP-MS) at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute (AORI), the University of Tokyo (UTokyo), after spiking with 5 µl of indium (1 µg/g) solution55. The remaining solution was spiked with 1 ml of a 0.097 mg/ml 9Be carrier before purification using two solvent extractions of acetylacetone in the presence of EDTA followed by precipitation of Be(OH)2 with NH4 (ref. 56,57). The resulting hydroxide was converted to BeO powder using a microwave ceramic crucible58 before being mixed with niobium, inserted into a copper cathode, and measured by a National Electrostatic Corporation accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) at the UTokyo Micro Analysis Laboratory, Tandem Accelerator (MALT)59.

Age-depth model

Radiocarbon analysis of two marine carbonate samples33 and seven bulk samples17 were previously obtained from KC-15. We provide a new age-depth model (Fig. S1) based on the modelling routine, Undatable, which uses the Bayesian 14C calibration software, MatCal, to take into account analytical uncertainty associated with 14C measurements and depth uncertainties of 2 cm (ref. 60). Carbon-14 ages were corrected for local effects17,61 and a marine reservoir effect (ΔR) of 900 ± 100 years (ref. 62) prior to calibration using the Marine13 curve63. Undatable was run for 106 iterations using a bootstrapping percentage of 20% and a Gaussian SAR uncertainty factor of 0.1 (ref. 60).

Data availability

All data generated in this study are included in the Supplementary information file.

References

Meredith, M. et al. Polar regions. Chapter 3, IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (IPCC, 2019).

Mouginot, J., Rignot, E. & Scheuchl, B. Sustained increase in ice discharge from the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica, from 1973 to 2013. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1576–1584 (2014).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J., Morlighem, M., Seroussi, H. & Scheuchl, B. Widespread, rapid grounding line retreat of Pine Island, Thwaites, Smith, and Kohler glaciers, West Antarctica, from 1992 to 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 3502–3509 (2014).

Steig, E. J., Ding, Q., Battisti, D. & Jenkins, A. Tropical forcing of Circumpolar Deep Water inflow and outlet glacier thinning in the Amundsen Sea Embayment, West Antarctica. Ann. Glaciol. 53, 19–28 (2012).

Ding, Q., Steig, E. J., Battisti, D. S. & Küttel, M. Winter warming in West Antarctica caused by central tropical Pacific warming. Nat. Geosci. 4, 398–403 (2011).

Steig, E. J. et al. Recent climate and ice-sheet changes in West Antarctica compared with the past 2,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 6, 372–375 (2013).

Wille, J. D. et al. West Antarctic surface melt triggered by atmospheric rivers. Nat. Geosci. 12, 911–916 (2019).

Pollard, D., Chang, W., Haran, M., Applegate, P. & DeConto, R. Large ensemble modeling of the last deglacial retreat of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet: comparison of simple and advanced statistical techniques. Geoscientific Model Dev. 9, 1697–1723 (2016).

DeConto, R. M. & Pollard, D. Contribution of Antarctica to past and future sea-level rise. Nature 531, 591–597 (2016).

Yokoyama, Y. & Purcell, A. On the geophysical processes impacting palaeo-sea-level observations. Geosci. Lett. 8, 1–19 (2021).

Larter, R. D. et al. Reconstruction of changes in the Amundsen Sea and Bellingshausen sea sector of the West Antarctic ice sheet since the last glacial maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 100, 55–86 (2014).

Hillenbrand, C.-D. et al. West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat driven by Holocene warm water incursions. Nature 547, 43–48 (2017).

Johnson, J. S. et al. Rapid thinning of Pine Island Glacier in the early Holocene. Science 343, 999–1001 (2014).

Johnson, J. S. et al. Deglaciation of Pope Glacier implies widespread early Holocene ice sheet thinning in the Amundsen Sea sector of Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 548, 116501 (2020).

Johnson, J. S. et al. Comparing glacial‐geological evidence and model simulations of ice sheet change since the last glacial period in the Amundsen Sea sector of Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surface, e2020JF005827 (2021).

Jakobsson, M. et al. Geological record of ice shelf break-up and grounding line retreat, Pine Island Bay, West Antarctica. Geology 39, 691–694 (2011).

Minzoni, R. T. et al. Oceanographic influences on the stability of the Cosgrove Ice Shelf, Antarctica. Holocene 27, 1645–1658 (2017).

von Blanckenburg, F. & Bouchez, J. River fluxes to the sea from the oceanʼs 10Be/9Be ratio. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 387, 34–43 (2014).

Kusakabe, M. et al. Distribution of10Be and9Be in the Pacific Ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 82, 231–240 (1987).

Kusakabe, M., Ku, T.-L. & Southon, J. R. Beryllium isotopes in the ocean. Geochem. J. 24, 263–272 (1990).

Lao, Y. et al. Transport and burial rates of10Be and231Pa in the Pacific Ocean during the Holocene period. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 113, 173–189 (1992).

Von Blanckenburg, F., Bouchez, J., Ibarra, D. E. & Maher, K. Stable runoff and weathering fluxes into the oceans over Quaternary climate cycles. Nat. Geosci. 8, 538–542 (2015).

Wittmann, H., von Blanckenburg, F., Mohtadi, M., Christl, M. & Bernhardt, A. The competition between coastal trace metal fluxes and oceanic mixing from the 10Be/9Be ratio: implications for sedimentary records. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8443–8452 (2017).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Widespread collapse of the Ross Ice Shelf during the late Holocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, 2354 (2016).

Frank, M. et al. The dissolved Beryllium isotope composition of the Arctic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6114–6133 (2009).

Raisbeck, G., Yiou, F., Jouzel, J. & Stocker, T. Direct north-south synchronization of abrupt climate change record in ice cores using Beryllium 10. Climate 3, 541–547 (2007).

White, D. A. et al. Beryllium isotope signatures of ice shelves and sub-ice shelf circulation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 505, 86–95 (2019).

Sjunneskog, C., Scherer, R., Aldahan, A. & Possnert, G. 10Be in glacial marine sediment of the Ross Sea, Antarctica, a potential tracer of depositional environment and sediment chronology. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. At. 259, 576–583 (2007).

Sproson, A. D. et al. Beryllium isotopes in sediments from Lake Maruwan Oike and Lake Skallen, east Antarctica, reveal substantial glacial discharge during the late Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 256, 106841 (2021).

Scherer, R. P. et al. Pleistocene collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Science 281, 82 (1998).

Graly, J. A., Corbett, L. B., Bierman, P. R., Lini, A. & Neumann, T. A. Meteoric 10Be as a tracer of subglacial processes and interglacial surface exposure in Greenland. Quat. Sci. Rev. 191, 118–131 (2018).

Smith, J. A. et al. New constraints on the timing of West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat in the eastern Amundsen Sea since the Last Glacial Maximum. Glob. Planet. Change 122, 224–237 (2014).

Kirshner, A. E. et al. Post-LGM deglaciation in Pine Island Bay, West Antarctica. Quat. Sci. Rev. 38, 11–26 (2012).

Smith, J. A. et al. The marine geological imprint of Antarctic ice shelves. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–16 (2019).

Ibach, L. E. J. Relationship between sedimentation rate and total organic carbon content in ancient marine sediments. AAPG Bull. 66, 170–188 (1982).

Simon, Q. et al. Authigenic 10Be/9Be ratios and 10Be-fluxes (230Thxs-normalized) in central Baffin Bay sediments during the last glacial cycle: Paleoenvironmental implications. Quat. Sci. Rev. 140, 142–162 (2016).

Valletta, R. D., Willenbring, J. K., Passchier, S. & Elmi, C. 10Be/9Be ratios reflect Antarctic Ice Sheet freshwater discharge during Pliocene warming. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 934–944 (2018).

Shevenell, A. E., Ingalls, A., Domack, E. & Kelly, C. Holocene Southern Ocean surface temperature variability west of the Antarctic Peninsula. Nature 470, 250–254 (2011).

Saunders, K. M. et al. Holocene dynamics of the Southern Hemisphere westerly winds and possible links to CO2 outgassing. Nat. Geosci. 11, 650–655 (2018).

Voigt, I. et al. Holocene shifts of the southern westerlies across the South Atlantic. Paleoceanography 30, 39–51 (2015).

Koutavas, A. & Sachs, J. P. Northern timing of deglaciation in the eastern equatorial Pacific from alkenone paleothermometry. Paleoceanography 23, PA4205 https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001593 (2008).

Toggweiler, J. R., Russell, J. L. & Carson, S. R. Midlatitude westerlies, atmospheric CO2, and climate change during the ice ages. Paleoceanography 21. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005PA001154 (2006).

Dang, H. et al. Pacific warm pool subsurface heat sequestration modulated Walker circulation and ENSO activity during the Holocene. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0402 (2020).

Scott, R. C., Nicolas, J. P., Bromwich, D. H., Norris, J. R. & Lubin, D. Meteorological drivers and large-scale climate forcing of West Antarctic surface melt. J. Clim. 32, 665–684 (2019).

Skinner, C. B., Lora, J. M., Payne, A. E. & Poulsen, C. J. Atmospheric river changes shaped mid-latitude hydroclimate since the mid-Holocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 541, 116293 (2020).

Fudge, T. et al. Variable relationship between accumulation and temperature in West Antarctica for the past 31,000 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3795–3803 (2016).

Bell, R. E., Banwell, A. F., Trusel, L. D. & Kingslake, J. Antarctic surface hydrology and impacts on ice-sheet mass balance. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 1044–1052 (2018).

Johnson, J. S. et al. The last glaciation of Bear Peninsula, central Amundsen Sea Embayment of Antarctica: Constraints on timing and duration revealed by in situ cosmogenic 14C and 10Be dating. Quat. Sci. Rev. 178, 77–88 (2017).

Stone, J. O. et al. Holocene deglaciation of Marie Byrd land, west Antarctica. Science 299, 99–102 (2003).

Mulvaney, R. et al. Recent Antarctic Peninsula warming relative to Holocene climate and ice-shelf history. Nature 489, 141–144 (2012).

Pike, J., Swann, G. E., Leng, M. J. & Snelling, A. M. Glacial discharge along the west Antarctic Peninsula during the Holocene. Nat. Geosci. 6, 199–202 (2013).

Etourneau, J. et al. Holocene climate variations in the western Antarctic Peninsula: evidence for sea ice extent predominantly controlled by changes in insolation and ENSO variability. Climate 9, 1431–1446 (2013).

Pollard, D. & DeConto, R. M. Modelling West Antarctic ice sheet growth and collapse through the past five million years. Nature 458, 329–332 (2009).

Golledge, N. R. et al. Antarctic contribution to meltwater pulse 1A from reduced Southern Ocean overturning. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–10 (2014).

Sproson, A. D., Aze, T., Behrens, B. & Yokoyama, Y. Initial measurement of beryllium‐9 using high‐resolution inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry allows for more precise applications of the beryllium isotope system within the Earth Sciences. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 35, e9059 (2021).

Kohl, C. & Nishiizumi, K. Chemical isolation of quartz for measurement of in-situ-produced cosmogenic nuclides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 3583–3587 (1992).

Bourles, D., Raisbeck, G. M. & Yiou, F. 10Be and 9Be in marine sediments and their potential for dating. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 443–452 (1989).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. In-situ and meteoric 10Be and 26Al measurements: improved preparation and application at the University of Tokyo. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. At. 455, 260–264 (2019).

Matsuzaki, H. et al. Multi-nuclide AMS performances at MALT. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. At. 259, 36–40 (2007).

Lougheed, B. C. & Obrochta, S. P. A rapid, deterministic age-depth modeling routine for geological sequences with inherent depth uncertainty. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 122–133 (2019).

Hillenbrand, C. D. et al. Age assignment of a diatomaceous ooze deposited in the western Amundsen Sea Embayment after the Last Glacial Maximum. J. Quat. Sci. 25, 280–295 (2010).

Berkman, P. A. & Forman, S. L. Pre‐bomb radiocarbon and the reservoir correction for calcareous marine species in the Southern Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 363–366 (1996).

Reimer, P. J. et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887 (2013).

Mouginot, J., Scheuchl, B. & Rignot, E. Mapping of ice motion in antarctica using synthetic-aperture radar data. Remote Sens. 4, 2753–2767 (2012).

Rignot, E., Mouginot, J. & Scheuchl, B. Ice flow of the antarctic ice sheet. Science 333, 1427 (2011).

Bindschadler, R. et al. The Landsat image mosaic of Antarctica. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 4214–4226 (2008).

Matsuoka, K., Skoglund, A., Roth, G., Tronstad, S. & Melvær, Y. Quantarctica, vol 10 (Norwegian Polar Institute, 2018).

Cuffey, K. M. et al. Deglacial temperature history of West Antarctica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14249–14254 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Matsuzaki (Univ. of Tokyo) and members of MALT for their assistance with AMS measurements. A.D.S. and Y.Y. would like to thank the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for supporting this study through their postdoctoral fellowships (PE17712 and P18791) and Grants-in-Aid (KAKENHI) for Scientific Research (20H00193 and 18F18791), respectively. The sediment core and geophysical work of the OSO-0910 cruise was funded by the NSF/ARRA ANT-0837925 grant awarded to John B. Anderson and Martin Jakobsson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D.S. together with Y.Y. and R.L.T. wrote the manuscript. Y.Y. designed the research. R.L.T. supplied samples from the OSO-0910 cruise. A.D.S. prepared samples for isotopic analysis. A.D.S and Y.M. conducted 10Be measurements using AMS. A.D.S and T.A. conducted 9Be measurement using ICP-MS. A.D.S conducted statistical analysis of all data sets from the OSO-0910 cruise. All authors provided review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Quentin Simon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sproson, A.D., Yokoyama, Y., Miyairi, Y. et al. Holocene melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet driven by tropical Pacific warming. Nat Commun 13, 2434 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30076-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30076-2

This article is cited by

-

Fluctuating sea-level and reversing Monsoon winds drive Holocene lagoon infill in Southeast Asia

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Enhanced subglacial discharge from Antarctica during meltwater pulse 1A

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.