The most interesting basketball game in Atlanta on a Friday night in March wasn’t the one played in the city’s downtown NBA arena. It was happening three miles north, between six-figure-earning teenagers in a gym that opened only seven months earlier as part of a league that didn’t exist one year before and whose primary audience couldn’t watch the action unfold live.

Tipoff of the second game of a playoff series to determine the inaugural champion of Overtime Elite, a three-team league featuring some of the country’s top players from ages 16 to 18, was still hours away when Ausar Thompson stopped by an always-open snack bar on the first floor of the league’s headquarters.

Emerging from his team’s shootaround, he grabbed a bowl of proteins and grains on his way to rest and prepare in the league-provided apartment he shared with his identical twin, Amen, and another league player in the upscale Atlantic Station neighborhood nearby.

“I’m confident,” he said of his team’s chances.

A 6-foot-6 wing with preternatural playmaking and impeccable manners, whose skills one league staffer breathlessly compared to the athleticism of Russell Westbrook and passing of Jason Kidd, Thompson was raised in San Leandro, Calif., began high school in Florida and once considered taking the conventional route to reach his NBA dream. Kentucky was his school of choice, though Florida State had impressed as well.

Then last year, recruiters called the brothers touting an attractive yet unproven alternative known by its three initials: OTE.

At the time, the New York-based social media company Overtime, founded in 2016, could only provide blueprints of a still-under-construction league to launch in the fall of 2021. Players would attend an in-house school and earn Georgia-accredited diplomas. They would earn guaranteed salaries of at least $100,000 and be provided with financial support if players wanted to later attend college as a student. The biggest selling point was basketball.

“We both wanted to go to college,” Ausar said. “But then we realized that we could get a lot better in this year than we would have gotten in high school.”

He arrived at that idea because of the three-story league headquarters the size of a city block where players could access a state-of-the-art show court, two practice courts, weight rooms rivaling an NBA practice facility, and coaches with NBA and college experience.

They were only the third and fourth players to commit, and by taking the salary they elected to forgo their NCAA eligibility should the best-laid plans not work out. Joining, Amen Thompson recalled, was a “leap of faith.”

“You just had to like, really trust them,” he said. “And then they actually ended up doing what they said they were going to do.”

Just as the Thompsons believed their best route to the NBA went through Overtime Elite, the league was founded on a conviction that millions of Gen Z, cord-cutter and cord-never users — and the brands that covet that demographic — would follow those journeys through social media, one post at a time.

Overtime chief executive Dan Porter wouldn’t say how much it cost to get the league up and running. “I can say,” he added, “it cost us a gallon of blood, two gallons of sweat and three gallons of tears.”

In transforming from a theoretical league to proof-of-concept, OTE has become one of American sports’ most closely watched experiments. Overtime had attracted investors such as a fund run by Jeff Bezos, along with Carmelo Anthony, Drake, Kevin Durant and Klay Thompson, but observers say its league’s first year legitimized the basketball side by offering evidence it could develop its top-level talent. It could affect your favorite alma mater’s recruiting class, or develop your favorite NBA team’s future rookie.

“It’s their first year, and at the end of the day, there are going to be growing pains,” said one NBA scout who had watched Overtime Elite play and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I came away thinking that it was better than I thought it would be.”

Along with the two-year-old G League Ignite, the NBA-sponsored team that signs high school graduates and tutors them for one year before they become eligible for the draft, Overtime has shown it can be a “disruptor” to the NCAA, said Jay Bilas, the ESPN college basketball analyst.

“I wouldn’t call them any sort of existential threat to the NCAA system because they’re not going to be taking all of the players,” Bilas said. “But they’ll be taking some of the top players, and that is certainly going to impact the college game.”

Because Overtime has yet to sell its live media rights for game broadcasts, wanting to first build its social following, it registers most with its young fans. On TikTok, Overtime’s general account has 19 million followers and Overtime Elite’s account surpassed 1 million in May — more than 25 NBA teams.

The NBA gathered this week for its annual scouting combine in Chicago, with a few OTE players participating. The bigger impact could come in one year. The prospect of the Thompsons attending and becoming first-round 2023 lottery selections — as some NBA observers believe is possible — is a feat that Overtime Elite believes will help it land on the radar of mainstream fans.

“When Amen and Ausar walk across that stage and shake hands with [NBA Commissioner] Adam Silver next year, there’s going to be a lot of people who lean to their friends while they’re watching the draft and say, ‘Oh, that’s the Overtime Elite kid I was telling you about,’ ” said Joe Leavitt, Overtime’s Los Angeles-based head of brand partnerships. “That’s a really interesting dynamic of this idea of discovery, and that’s frankly how we’ve gotten where we are.”

The OTE show court has room for more than 1,200 fans, but its most rabid following stems from those nowhere close to the building because this arena is engineered to be optimized for social media. One staffer dubbed it essentially a basketball version of the “TikTok mansion” — a place where creators put their enviable lives on display and fans watching through the players’ lens clamor to visit.

From the arena’s broadcast booth, action is narrated by AMP, a team of YouTube celebrities who reference music and culture as much as the box score. High-arching video boards along the sides lit in the league’s orange-and-blue motif shine brilliantly by high-definition lights found in only two other arenas — Crypto.com Arena and Brooklyn’s Barclays Center.

“We designed this hybrid of like, an NBA-caliber practice facility, a small schoolhouse and a show court sort of designed as ‘basketball meets inside your [video-game] console,’ ” said league commissioner Aaron Ryan in March, one month before he left the company, citing the “personal toll” of splitting time between work in Atlanta and his family in New Jersey.

Steps from the court is a room that is Overtime’s answer to the TV production truck — three rows of computers and color-coded boards controlling a wall of monitors that receive footage from at least 15 cameras on standard game nights. To put that in context, the broadcast of an NBA game at Crypto.com Arena typically uses about 11 cameras. That number jumped to 29 cameras during March’s best-of-three OTE finals series, a count that included at least five iPhones, nine cameras equipped for virtual reality, and 15 pro-style cameras, said Marc Kohn, Overtime’s chief content officer.

“It’s all the horsepower that a television or streaming network would have, but we just utilized it differently,” said Kohn, who arrived from digital-first Bleacher Report’s video department. “We think of just: What are the 50 pieces of content that we can create and distribute across all the different social channels?”

For now, live streaming is available only for players’ families on a closed circuit. Games are still spliced into quick-hitting highlights and delivered on social platforms by the five full-time social media employees who work for the league in a room dubbed “The Kitchen,” next to the production center. The league’s individual Instagram account has nearly 400,000 followers and drew at least one like or comment from 800,000 unique users during the first season, according to Comscore, the web analysis firm.

Surprising insights into its online audience have led Overtime to post condensed game recaps sometimes 50 minutes long on YouTube. On the internet, that’s an eternity. But demand from viewers watching longer than expected, with a significant portion on connected televisions, prompted the longer uploads.

The footage, plus more gathered throughout the week, eventually flows to a first-floor room housing six rows of desks where more employees work on documentary features.

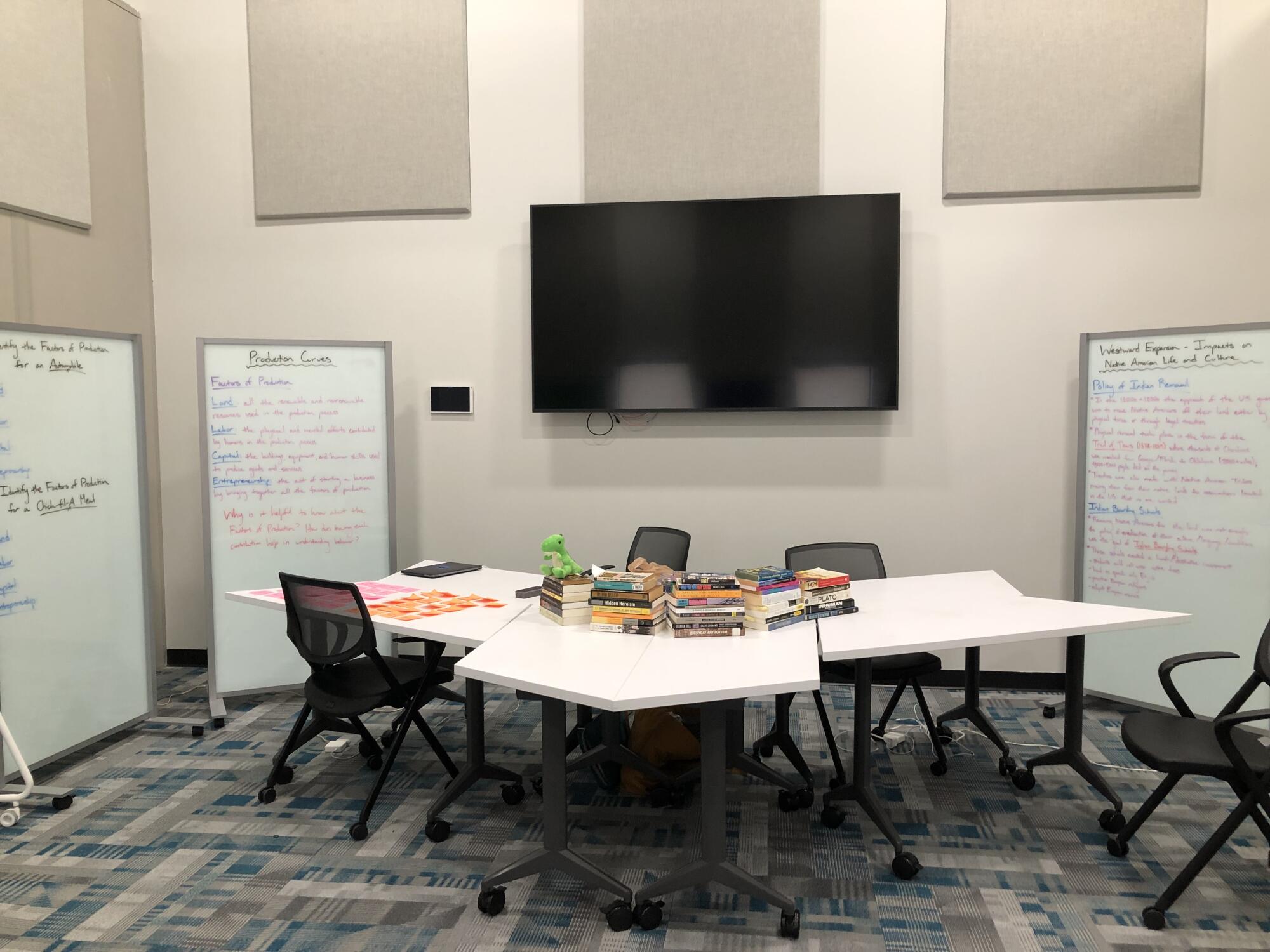

Viewers might see the school in one, high-ceilinged hallway whose common areas are broken into rooms for different subjects. One whiteboard listed a history lesson on the Trail of Tears. Another showed the remnants of a business lesson — the components of everything that goes into a Chick-fil-A meal. Players’ days are structured into blocks, with basketball in the morning and school in the afternoon, that flip-flop the next day.

Viewers might also see the dining area, splashed with Gatorade logos, the basket stanchions wrapped in State Farm’s logo, the winter dunk competition that was broadcast in virtual reality within Meta Quest, Facebook’s virtual-reality headsets, and the Topps trading cards with players’ images. They are the result of “brand partnerships” Leavitt helped orchestrate that he called multiyear, multimillion-dollar deals.

“We make money the same way other sports leagues do — we build a robust sponsorship pipeline, group licensing around trading cards and more,” Porter said. “We also build media rights and grow those over time starting with an already engaged Overtime audience.”

That digital audience wants to see the dunks, daily life and personality of players such as Jahzare Jackson, a soft-spoken center who stands 6-foot-11, 315 pounds and grew up in Oceanside. After playing in middle school with social-media phenom Mikey Williams and teaming up on the AAU circuit with Bronny James, living under the camera’s watchful eye had become “second nature,” Jackson said.

“You really have to be working with somebody to escape it,” Amen Thompson said. “But it’s fun knowing that if one person doesn’t get [the shot], then the other person’s going to get it.”

When the Thompson brothers began high school in Florida, their father came with them. For this season, both parents are in San Leandro, and Ausar has enjoyed the extra freedom.

“The only thing is,” he said, “now I’ve got to wash my own stuff.”

The league’s soaring ambitions and corporate backing could obscure that often the most pressing daily issues revolve around how to manage and support more than 20 teenagers living and training in close proximity, many for the first time away from their loved ones. Players missed their families. They learned to redirect conversations when friends asked how much money they were making. With help from a company that taught players financial literacy, Jackson was learning to prepare and file his taxes for the first time.

“Forget the basketball, like, does he need Tylenol, or does he like swallowing pills yet?” said Brandon Williams, a former Sacramento Kings executive who oversees Overtime’s basketball operations. “There are kind of life lessons in everything when you have a 16-year-old, 17-year-old.”

Employees felt strongly those lessons would help when their second season launches in the fall. Williams’ top priority is a tougher schedule, saying he’d like to face G League Ignite. By the time the league was announced, most U.S. teams were already booked for the 2021-22 season, leaving a smattering of lower-level squads to face. In addition, COVID wiped out a planned trip to Europe.

The best competition on their 23-game schedules usually came against OTE teams. The familiarity between Overtime’s teams had a way of increasing the intensity rather than dulling it. One game in March ended with a heated scrap, coaches holding back players and disciplinary action. The footage spread, of course, on social media.

There are growing pains. Yet OTE has already fulfilled part of its mission — attracting up-and-coming talent it hopes will sustain interest and follower growth. Naasir Cunningham, rated by 247Sports as the top player in the 2024 class, committed in April with a twist: He will not take a salary to maintain his NCAA eligibility, though the 6-foot-7 wing from New Jersey still can earn money off his name, image and likeness.

Bilas said that though Overtime’s guaranteed six-figure salaries drew initial headlines, they are just one factor players must consider, particularly now that the explosion of sanctioned cash available within the NCAA thanks to NIL deals has left college teams able to compete monetarily.

Colleges can offer the spotlight of March Madness. If the ultimate goal is the kind of NBA contract that can dwarf the money offered by Overtime Elite, G League Ignite or college NIL deals, then it becomes a question of player development. Ausar Thompson spoke glowingly of all-hours access to the gym. Amen Thompson’s offseason plans included preparation for next year’s pre-draft workouts. Players consult with Damien Wilkins, a 10-year NBA veteran who is Overtime’s “dean of athlete culture and experience.”

“In the G League and Overtime Elite, you’re more likely going to be working maybe even more on your game than you do in college and you’re going to be doing it with an NBA system,” Bilas said. “So there’s an argument to be made that you can develop as an athlete just as well if not better and those two options would argue it’s a better path to development.”

Former NBA player Ryan Gomes and former DePaul and Virginia coach Dave Leitao are on a coaching staff overseen by 13-year NBA guard and former Connecticut coach Kevin Ollie. One NBA scout expected the influence of the coaching to be more evident, the play more disciplined.

“At first, when they would introduce a bunch of new plays to me, I was like, ‘Oh, what am I doing?’ ” Ausar said. “Now I feel like there’s a pattern to basketball and I’m learning it.”

Joining OTE, Ausar said, is not for prospects unwilling to treat it like a job.

“You have to come in with a certain mindset,” he said. “You have to be prepared.”

Hours later inside the show court, Ausar scored 17 points by making 63% of his shots to help Team Elite even its championship series against Team OTE, which was headlined by his brother. Two days later, Ausar earned most-valuable-player honors and sealed a championship by scoring 20 points, making 53% of his shots.

Fans curious how the brothers could fit in the NBA will have to wait until 2023. Until then, they’ll have to go online and tap the “follow” button.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.