By Haley Elder, Audrey Hertel and Jordan Opp

Jenny Synowiecki vividly remembers spending her summer days playing in her dad’s backyard, a wooded area where she would build forts with her brother and watch the trains pass by, urging the conductors to blow their horns.

“We were successful at a few attempts,” she said.

Nearly 20 years later, on the day before Thanksgiving in 2021, the Omaha World-Herald published an article, announcing a $100 million-plus health campus could be built in that same area.

That’s how Synowiecki found out the Omaha neighborhood she grew up in, and the one where some of her family still lives, was a prospective area for development.

After reading the article, Synowiecki said she became concerned relatives would soon have to pack up and leave an area that holds so many of her favorite memories. She began passing out flyers for upcoming meetings and informing neighbors how it may impact their homes and how they can voice their concerns to city government officials.

Stories like Synowiecki’s occur everywhere, not just in Nebraska. People all over the country are talking about gentrification, where developers enter areas of a city to build, rebuild or renovate architecture and landscapes. This draws in new businesses and residents while increasing overall property value.

Although there are varying definitions and ideas of gentrification, it typically implies a level of displacement.

The Urban Displacement Project describes gentrification developments as an economic change that occurs in disinvested areas. Wealthier investors and residents move in, which often changes demographics of that area including income, education and racial make-up. It also says historic conditions, a city’s pattern of disinvestment and investment and community impact are important to consider with gentrification.

And gentrification is on the rise.

According to Governing’s analysis of the 2009-2013 American Community Survey, almost 20% of low-income neighborhoods in the United States’ top 50 cities have undergone gentrification since the 2000 census, a stark change from the 9% in the 1990s.

This increase in gentrification can lead to instances like those happening in Omaha, where new developments worry community members. According to this same analysis, Omaha gentrified 21.4% of areas eligible.

Gentrification also is polarizing.

Many organizations, people, economies and governments are involved in the development of properties. But some developers are challenging the narrative of gentrification by placing an emphasis on empowering community members and minimizing displacement.

Either way, people with differing approaches to the urban development process go into projects hoping for the best outcomes — thriving hubs for community and a rise in the local economy.

Eric Englund, the assistant planning director for urban planning at the City of Omaha, spends his days working on numerous urban development projects. Englund is involved in development processes from start to finish and has seen how projects impact the economy and community members alike. He explained that new developments can greatly benefit areas of the city.

“When you have great economic development and new projects, it can have a great effect and spillover into the surrounding neighborhoods,” Englund said.

Eric Englund, the assistant director for urban planning at the City of Omaha Planning Department discusses how new developments can impact surrounding areas and how community members are involved in development processes.

There are projects that aim to prevent displacement but still reinvest in areas. These initiatives —â which balance bringing in new resources and maintaining community —â are known as revitalization.

Englund said information given to city staff on new development projects is not available to the public until an application for the project to get on the planning board agenda has been made. He explained that this occurs because there’s a possibility a project will not proceed.

Once the information regarding a project is publicly accessible, Englund said community members have concerns or want to see the project and plans, they can reach out to City Planning and ask questions.

However, Englund said his team encourages developers to involve community members in development conversations from the very beginning and throughout the process.

After all, they’re the ones who may have to move if prices get too high.

But in her old South Omaha neighborhood, Synowiecki said she thinks the development company — Community Health Development Partners — has made very little effort to involve the community in planning the project, known as The Intersections.

“I feel like people are being taken advantage of, and like, I feel like I can see that from a mile away,” Synowiecki said. “Just because of the lack of communication, the lack of community involvement, the strategic way in which they're going about it. It's very clear to me like this isn't about trying to help a community.”

But Community Health Development Partners officials disagree. Their representatives have met with more than 75 community organizations, held one-on-one meetings with residents and city leaders and participated in public meetings, said Kristi Andersen, a spokesperson for Community Health Development Partners.

In fact, David Lutz, Community Health Development Partners’ principal and senior managing director, said the project was announced while still in the planning phase in order to gauge community interest and allow for feedback.

The goal of The Intersections is to help the community, Andersen and Lutz said.

"The purpose of The Intersections is to connect and bridge some of the gaps and barriers that we know exist in our community when it comes to sports, health, wellness, accessibility,” Andersen said. “Community Health Development Partners is a community developer that specifically chose this location to revitalize the area and provide needed services to an underserved community.

Lutz said the company is not a typical developer that would “develop this thing and flip it to somebody and move on with our lives.”

He added: “We’re extremely community-focused. And, I mean, we're community developers at the end of the day.”

The Intersections is described as a recreation and wellness campus, offering a hub for sports, health and entertainment, according to its website.

Its campus is planned to span 25 acres with five facilities, which will be used for a variety of sports, health, wellness and community activities. The proposed campus is bounded generally by Martha Street on the north, Deer Park Boulevard on the south, Interstate 480 to the west and the Union Pacific railroad tracks to the east. The location, which currently has around 50 homes and a large industrial area, allows easy access to Interstate 80.

The area was recently designated as a Community Redevelopment Area, meaning The Intersections would qualify for Tax Increment Financing. TIF is a tool used by the City of Omaha to encourage the private sector to partner with the City of Omaha to accomplish economic and community development. TIF is used throughout Nebraska but has been an important tool in developments throughout Omaha.

According to Synowiecki, the community directly surrounding the development has been left out of the loop. She said her family, who lives in the 27th Avenue and Martha neighborhood, was unaware of the development until the Omaha World-Herald article was published on Nov. 24. Less than three weeks later, the first home sale occurred on Dec. 8, according to the Douglas County Assessor website.

CHDP has attended community meetings since the development was announced, one of which was hosted by the Deer Park Neighborhood Association, which governs Synowiecki’s old neighborhood.

Synowiecki said the main concern for many residents was losing their homes or having to live in the middle of the development.

Since announcing the project, Community Health Development Partners has purchased 22 properties in the area as of May 2022, according to the Douglas County Assessor website. Two of the properties did not have houses.

According to the assessor's website, the average sale price per home is $167,618, which would be 59% over their valuations.

“We want the people to be excited about the project,” Lutz said. “We want the people to feel like they're getting an amazing offer for their house, and it can help them go on to a better place.”

For some of the homeowners who sold their houses to CHDP, this means finding a new home in a different area but there is a possible obstacle in their path — Omaha’s housing affordability crisis.

For context, the median listing price for a home in Omaha is $240,000, according to realtor.com.

Synowiecki said she didn’t think CHDP showed much interest in preserving the community in her old neighborhood — a common complaint among residents facing new development.

Some organizations in Omaha are taking extra steps to ensure community members are prioritized during development in different areas.

Spark, a non-profit in North Omaha, aims to honor community members, propose affordable housing projects and draft policies that could help prevent displacement during and after development. Spark’s mission is to help transform disinvested neighborhoods into thriving communities. It places an emphasis on community, sustainability and integrity, according to its website.

Manuel Cook, urban development manager of Spark, has been leading Forever North, a project he said is trying to develop North Omaha into a community that values its existing members while attracting new residents.

To avoid the displacement of community members, Forever North focuses on the quality of life for the area’s current residents by increasing transportation and access to basic needs, according to the plan’s strategy document. The Forever North project includes plans to create space for new businesses to complement the existing ones and create more affordable housing opportunities.

This illustration shows how the Forever North project would transform the intersection of North 24th and Lake streets.

While developing the plans for Forever North, Cook created a space for community-focused conversations. He began working with the community in 2019. He held office hours three days a week, along with workshops and community meetings.

Cook continued to have conversations with the community, allowing for feedback and working to address any concerns his neighbors might have.

“I'm from North Omaha,” Cook said. “So I know a lot of people in the community. So it's easy to like communicate with people.”

One of these community members is Marcey Yates, founder and director of Culxr House.

Yates is listed as a stakeholder in Forever North and has been active in empowering the residents of the area through his work at Culxr House — a safe space and community hub for artists, activists, entrepreneurs and creatives to grow their skills.

Located in North Omaha, Culxr House is in an area where people are trying to make positive change and raise up the next generations through art, according to Yates.

He said he hopes Culxr House can continue to be a representation of the community.

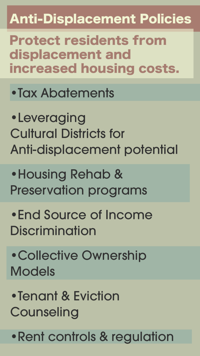

Working in development has led Cook to see the importance of honoring communities. In addition to his work on the Forever North project, Cook said he has written and delivered anti-displacement policy proposals to city government officials but has yet to receive a response.

“I’ve given it to the city three times …” Cook said. “So it's really on them to enact some of those because it's policy related on that level.”

Cook said occurrences like gentrification are two-fold — there’s investment and displacement.

People typically have positive attitudes toward investment, according to Cook. He explained these investments do increase the quality of life in that area. He noted that they come with the downside of increased taxes, which can create economic challenges.

Protecting residents from increased housing costs with tax abatements, developing grants for housing rehabilitation efforts and creating affordable housing opportunities are all policies Cook said he has proposed to help developments avoid displacement.

He said the more affordable housing you have in areas being invested in, the more community members can remain there.

“A community is a people, a culture is the people, so if you displace them economically, then you don’t have that same community anymore, or culture,” Cook said. “If you take all the opportunities for people to develop and define their way of life, then you also take away culture from an area.”

This is an archived article. The formatting may differ from when it was originally published.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.