The Defiant Strangeness of Werner Herzog

The director brings his signature theme—adventurers who share his quixotic compulsions—to his debut novel.

Twenty-five years ago, while in Tokyo directing an opera, the German filmmaker Werner Herzog turned down the offer of a private audience with the emperor of Japan. “It was a faux pas, so awful, so catastrophic that I wish to this day that the earth had swallowed me up,” Herzog writes in the preface to his first novel, The Twilight World. Nonetheless, his hosts wondered whether he might like to meet some other Japanese celebrity. Without hesitation, he asked to visit Hiroo Onoda.

Even if you don’t recognize the name, there’s a good chance that you are familiar with Onoda as a legend, a symbol—what we might nowadays call a meme. A lieutenant in the Imperial Army during World War II, stationed on the Philippine island of Lubang, he kept fighting long after the Allied victory, until he was finally relieved of his duties in 1974. Onoda wasn’t the only Japanese soldier to wage a lonely, endless war. Shoichi Yokoi was captured in Guam in 1972 and, like Onoda, struggled to make peace with the radically altered reality of postwar Japan.

Beyond their home country, these men have come to serve as illustrations in an informal dictionary of received ideas, accompanying the entries for fanatical loyalty, fighting the last war, and general cluelessness. The guy who stays in the field long after the war is over is, to modern eyes, a comical, cautionary figure, an avatar of patriotism carried to ridiculous extremes. We rarely pause to look for motives other than blind obedience, or to imagine what those years of phantom combat in the wilderness must have felt like.

In making Onoda the subject of his first novel—a slender chronicle rendered in efficient, idiosyncratic English prose by the poet and translator Michael Hofmann—Herzog declines to treat him as a joke. He is clearly fascinated by the absurdity of this hero’s situation, and also determined to defend the dignity of a man who had no choice but to persevere in an impossible mission.

The orders Onoda receives from his commanding officer in December 1944 could hardly be more explicit, at least as Herzog renders them:

As soon as our troops have been withdrawn from Lubang, it is your duty to hold the island until the Imperial Army’s return. You are to defend its territory by guerrilla tactics, at all costs. You will have to make your own decisions. No one will give you orders. You must be self-reliant.

As the years go by with no sign of the army, Onoda interprets evidence of Japan’s defeat—including leaflets dropped from the sky—as Allied propaganda. Near the end of his ordeal, he is baffled by the movements of American planes and ships that are heading west, toward Vietnam. The account of geopolitics he gleans from his observations is that, in 1971, “India … has freed itself from the British, and Siberia has split away from Russia. They have now joined Japan, to form a powerful triple alliance against America.”

Onoda isn’t entirely alone in his isolation. During his time on Lubang, he leads a small squad of similarly unlucky, but lower-ranking and somewhat less zealous comrades: a corporal named Shimada and two privates, Kozuka and Akatsu. His instructions to them are an echo of the orders he was given: “The war is different now, heroic gestures have no place. Our tasks are to remain invisible, to deceive the enemy, to be ready to do seemingly dishonorable things while keeping safe in our hearts the warrior’s honor.” And so they live like bandits or ancient hunter-gatherers, foraging in the bush and stealing from the local peasants, pilfering crops, killing the occasional water buffalo, and learning to extract oil from wild coconuts. They are both the hunters and the hunted: “In the thirty years, just under, of his solitary war,” Herzog writes, “Onoda will survive one hundred eleven ambushes.”

His solitary war. Even when he is with Shimada, Kozuka, and Akatsu, Onoda seems radically alone. Those three are pragmatic souls, trying to make it through rough circumstances under the command of an unyielding superior officer. As Herzog imagines him, Onoda operates on a wholly different level, his tactical acumen and delusional certainty infused with a pure warrior spirit. Rather than dramatizing those ambushes and similar adventures, The Twilight World emphasizes the existential dimensions of Onoda’s strange, looping odyssey in language that often veers from the concrete data of jungle sounds and smells into dizzying abstraction:

Onoda’s war is of no meaning for the cosmos, for history, for the course of the war. Onoda’s war is formed from the union of an imaginary nothing and a dream, but Onoda’s war, sired by nothing, is nevertheless overwhelming, an event extorted from eternity.

Whatever that last phrase might mean in this context—can three decades really be said to constitute a single event?—it could describe most of Herzog’s films. (Onoda’s war has been brought to the screen by the French director Arthur Harari, whose Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle premiered at Cannes in 2021.) Any movie might be said to represent a radical distillation and reshaping of time, an episode extracted, at significant cost in labor, money, and endurance, from the infinite flow of experience. Watching Herzog’s films, you somehow feel the weight of the infinite, the metaphysical shadows that bring the physical world into relief.

Herzog, who was born in Bavaria in 1942, has made more than 55 films since 1968, divided between documentaries and fictional features, though that is a distinction he disdains. (Roger Ebert, a critical champion of Herzog’s who became a friend, once wrote to him that “the line between truth and fiction is a mirage in your work.” That could also be said of The Twilight World.) Herzog is not interested in psychological or historical realism, or for that matter in literal facts, but in “ecstatic truth,” a quality that almost by definition eludes classification, residing as it does in a vatic realm of images, experiences, and feelings.

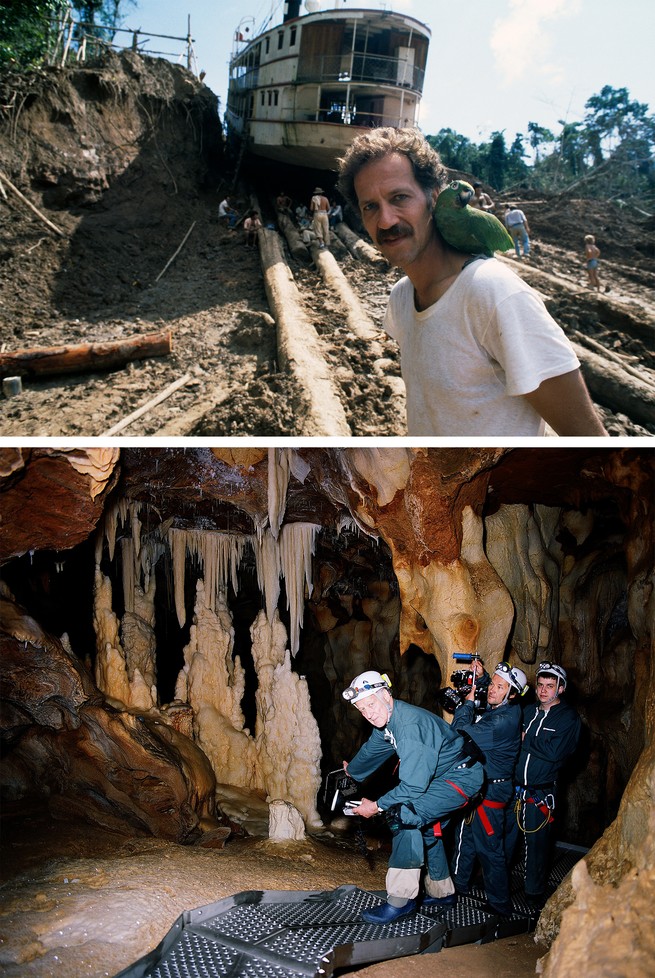

Reviewing Nosferatu, Herzog’s 1979 remake of F. W. Murnau’s silent vampire classic, the critic Dave Kehr noted, with some exasperation, Herzog’s defiance of the patterns and protocols of cinematic storytelling. “With its petulance over matters of form and development,” Kehr wrote, “Nosferatu sometimes made me wonder why Herzog was attracted to narrative filmmaking at all—why he hadn’t invested his talents in a more accommodating medium like photography or poetry.” The answer, which may be more apparent now than it was at that stage in Herzog’s career, is that accommodation is the last thing he wants. One of his previous books, a diary kept during the filming of his Amazonian epic, Fitzcarraldo (1982), is called Conquest of the Useless, a title that summarizes the grandiose, quixotic attitude that, more than any formal or aesthetic concern, has governed his approach to cinema.

“Let me offer a metaphor,” Herzog once said: “All my films have been made on foot.” It isn’t really a metaphor. Walking is the key to all Herzogian mythologies. His first book, Of Walking in Ice, chronicles a winter trek from Munich to Paris, undertaken in late 1974 out of a characteristic blend of magical thinking and practical determination. A beloved mentor, the critic Lotte Eisner, had fallen ill in France, and Herzog decided that if he went to visit her by the slowest, hardest, least accommodating means, she would stay alive until he got there. And so she did.

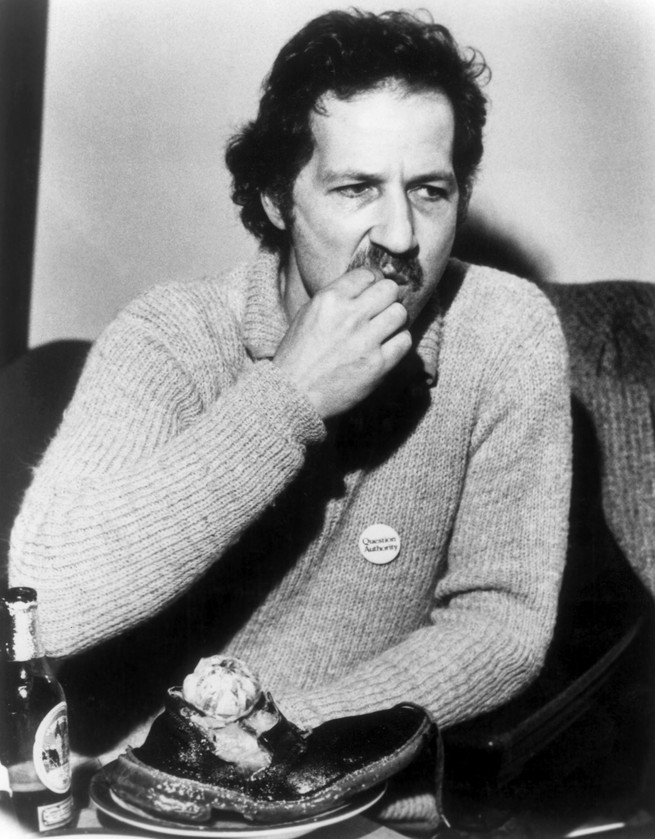

A few years later, an event took place at the UC Theatre, in Berkeley, California, that has been immortalized in a 20-minute documentary directed by Les Blank, forthrightly called Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe (1980). The shoe in question, an “ankle-high Clarks desert boot,” was prepared in the kitchen of Chez Panisse and consumed by Herzog in front of an audience gathered for a local premiere of his friend Errol Morris’s debut film, Gates of Heaven (1978). The intention was to teach a lesson and make good on a promise. As Herzog explained the stunt in an interview:

As a young man Errol had great talent as a cellist, but he suddenly abandoned the instrument, and dropped his book project after collecting thousands of pages of conversations with serial killers. Then he said he wanted to make a film, but complained about how difficult it was to find money from producers and that all the subsidies had dried up. I made it clear that when it comes to filmmaking, money isn’t important, that the intensity of your wishes and faith alone are the deciding factors. “Stop complaining about the stupidity of producers. Just start with a roll of raw stock tomorrow,” I told him. “I’ll eat the shoes I’m wearing the day I see your film for the first time.”

It might be more conventional, idiomatically, to say, “I’ll eat my hat,” but the shoe is in every way a more apt piece of apparel, both practically and symbolically. Herzog, who rejects the label “artist,” prefers to think of himself as a craftsman, a wanderer, “a foot soldier of cinema.” Filmmaking, though it may thrive in the marketplace of popular culture and occasionally ascend into the empyrean of the fine arts, is for him above all a physical activity, comparable among human endeavors to cooking and walking. (That Blank’s film unites those three practices secures its place in the Herzog canon.) “Cinema doesn’t come from abstract academic thinking,” Herzog has said; “it comes from knees and thighs, from being prepared to work twenty-hour days.” And as a craft, it is best learned not through schooling or industry ladder-climbing but through hard, real-world experiences. His advice to young filmmakers:

Beware of useless, bottom-rung secretarial jobs in film-production companies. Instead, so long as you are able-bodied, head out to where the real world is. Roll up your sleeves and work as a bouncer in a sex club or a warden in a lunatic asylum or a machine operator in a slaughterhouse. Drive a taxi for six months and you’ll have enough money to make a film. Walk on foot, learn languages and a craft or trade that has nothing to do with cinema.

“Walk on foot” could be the slogan of a man who seems constitutionally incapable of standing still. Herzog, who currently lives mainly in Los Angeles, has the distinction—unique in the history of the medium, as far as I know—of having shot at least one feature film on every continent, including Antarctica.

He is a character in many of his movies, in particular recent documentaries such as Grizzly Man (2005), Encounters at the End of the World (2007), Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), and Into the Abyss (2011). His unmistakable voice—the critic David Thomson calls it “one of the great incantatory elements in film”—has been heard in episodes of The Simpsons and in Penguins of Madagascar. Its owner has shown up on multiplex screens as a milky-eyed villain in the Tom Cruise vehicle Jack Reacher and in prime-time living rooms as an eccentric homeowner on an episode of Parks and Recreation. The man is something of a meme in his own right.

But his celebrity, his pop-culture ubiquity, shouldn’t diminish the power or domesticate the strangeness of his work, which amounts to a defense of individual idiosyncrasy—not only his own—in the face of standardization, groupthink, and cultural practices that are accommodating in the worst sense of the term. The Twilight World strikes me as too flimsy, too elliptical to count as essential Herzog, but it did send me back to his films with a renewed appreciation of what they put at stake and why they matter.

The best of them are, in a literal way, pedestrian: at once the representation and the result of hard travel, of journeys made one step at a time. Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), the film that brought Herzog international attention and the first of his five collaborations with the actor Klaus Kinski, follows the grueling, ill-fated slog of a group of Spanish conquistadores through the jungles of Peru. The fact that they are speaking German may detract from the verisimilitude, but strict naturalism has never been a priority of Herzog’s. What makes Aguirre so much more powerful than most other historical dramas, made with larger budgets and ostentatiously “epic” ambitions, is the sense of physical immediacy—of heavy mud and clanking armor, of danger and fatigue, of perseverance and fanaticism. Lasting a bit more than 90 minutes, it not only feels much longer, but is one of the only films about which that can be said as praise. Treading a fine, heretofore undiscovered boundary between tedium and intensity, it transports the audience into the hallucinatory reality of Aguirre and his comrades as they stumble through a strange and terrifying new world.

Aguirre also introduced what has become the most familiar Herzogian archetype. His oeuvre is crowded with solitary characters whose compulsions take them beyond the limits of conventional, rational behavior toward a mania that can feel—by turns or all at once—destructive, ridiculous, and sublime. Most of these avatars of extremity, real and invented, are men, with the notable exception of the British traveler and writer Gertrude Bell, played by Nicole Kidman in Queen of the Desert (2015). They include Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man, the adventurers played by Kinski in Fitzcarraldo and Cobra Verde (1987), and Dieter Dengler, a former U.S. military pilot and Vietnam-era prisoner of war who is the subject of both a 1997 documentary (Little Dieter Needs to Fly) and a 2006 scripted feature (Rescue Dawn, starring Christian Bale). The list goes on. Quixotic is a mild term for the compulsions that grip these people, and their adventures are more harrowing than anything Cervantes’s knight of the doleful countenance ever experienced.

Hiroo Onoda—a man on an “endless jungle march”—belongs in their company, as a not-so-secret sharer in the filmmaker’s hardships and obsessions. “We found much common ground in our conversations,” Herzog says of Onoda near the end of the book, “because I had worked under difficult conditions in the jungle myself and could ask him questions that no one else asked him.”

This is a dry, self-directed joke, and also a plainly literal statement. The affinity between Herzog and Onoda is evident on every page of The Twilight World, though to identify the author with his subject too closely would be a mistake. Herzog’s sympathy for his errant heroes is always evident, but so is the detachment required to represent them honestly, to find the truth that they themselves might be too absorbed in their own circumstances to see. It takes imagination to intuit the shape of a journey, and Herzog’s imagination, visual and literary, is above all located in the soles of his feet:

After all his millions of steps, he had understood that there was—there could be—no such thing as the present. Each step of the way was past, and each further step was future. The raised foot was past, the same foot placed in the mud in front of him still ahead.

This article appears in the June 2022 print edition with the headline “The Defiant Strangeness of Werner Herzog.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.