A selection of speakers and cultural events that campus has played host to over the years

UC Berkeley has historically been a magnet for African American activists, artists, and thinkers but never more so than during the tumultuous ’60s and ’70s. And with a little googling, many of these historical appearances can still be seen, heard, and savored online. In honor of the upcoming 45th annual Black History Month (February 2021), here’s a selection of Black speakers and cultural events that the Cal campus has played host to over the years.

On May 17, 1967, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered an anti-Vietnam speech before a packed Sproul Plaza in which he praised Berkeley students as “the conscience of our nation” and called for a revolution of values. “America has brought the nation and the world to an awe-inspiring threshold of the future,” King told the crowd. “And yet we have not learned the simple art of walking the earth as brothers and sisters.”

Four years earlier, on October 11, 1963, Minister Malcolm X was interviewed in Dwinelle Hall by sociology Professor John Leggett and then-graduate student Herman Blake. His appearance and Dr. King’s are a study in contrasts, as the Black Muslim leader spoke unequivocally in favor of Black separatism. White liberals and conservatives, X contended, differed “in the same way that the fox differs from the wolf. Their appetite is the same. Their motives are the same. It’s only their mannerisms and methods that differ.”

In addition to activists, Black musicians came to Cal as well—beaucoup, in fact. Between the Berkeley Blues Festival and the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, which ran from 1957 to 1970, some of the greatest blues musicians on earth, including Big Mama Thornton, Howling Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and Bessie Jones rocked the Greek Theatre, Pauley Ballroom, and other on-campus venues. For a taste, try the Arhoolie record, “Live! At The 1966 Berkeley Blues Festival,” recorded in Harmon Gym and starring Zydeco king Clifton Chenier, guitar virtuoso Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Texas songster Mance Lipscomb.

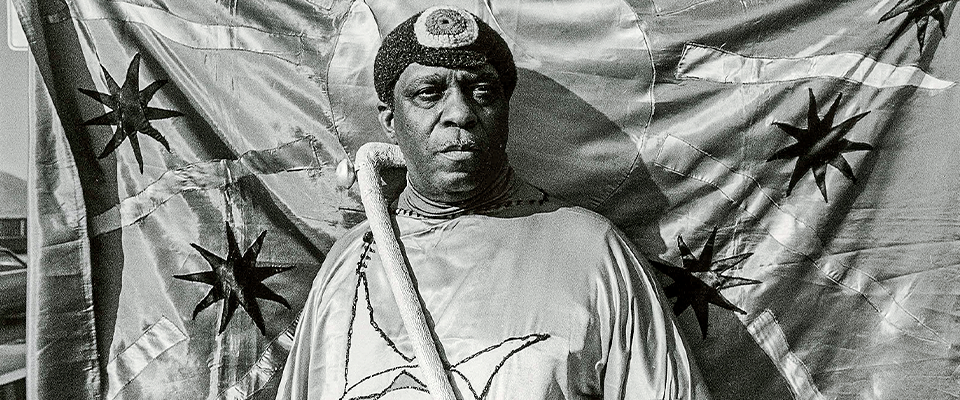

There was jazz too, of course, including the one and only Sun Ra, who came to Cal in spring 1971 as artist-in-residence and delivered a course called “The Black Man in the Cosmos.”

Decades before the term “Afrofuturism” was coined, Ra, born Herman Blount in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1914, seemed to embody the idea with his otherworldly costumes and tales of space travel. In his free-form classroom lectures, the galactic jazzman blended his own brand of myth, history, politics, and spirituality to define—or redefine—the Black experience. He liked to say, “History is only his story. You haven’t heard my story.” And, “My story is mystery.”

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the legendary African-American company, first performed in Berkeley in 1968 and returned every year thereafter, until COVID-19 canceled the planned 2020 appearance. As contributor Chinwe Oniah wrote on the 50th anniversary, “When the Alvin Ailey dancers are in the house, Zellerbach [Hall] can feel more like a church than a theater.” The spiritual overtones are no accident. Ailey’s successor, Judith Jamison, told the magazine, “Our job has been to lift people when they come and make sure they stay lifted when they leave.”

Cal has played host to countless authors over the years, but few as incisive as James Baldwin (The Fire Next Time, If Beale Street Could Talk), who delivered a speech in Wheeler Hall on Jan. 15, 1979, entitled “On Language, Race, and the Black Writer.” His words are by turns humorous and scathing, and always fiercely challenging, as when Baldwin recasts the Civil Rights Movement as a slave rebellion and stresses that there were no writers who could serve as his models as a child. “For example, I did not agree at all with the predicament of Huckleberry Finn concerning Nigger Jim. It was not, after all, a question about whether I should be sold back into slavery.” What every writer must realize, Baldwin told his audience, “is that he is involved in a language that he has to change.”