This week the U.S. Interior Department released a 100-page report on the lasting consequences of the federal Indian boarding school system.

You might recall last June Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo, announced the federal agency would investigate the extent of the loss of human life and legacy of the federal Indian boarding school system, a chapter of U.S. history many Americans know little to nothing about.

This week’s report is the first of possibly many, and it deserves to be read by as many Americans as possible.

Here are some of the investigation’s top-level findings:

- Beginning in the late 1800s, the federal government took Indian children from their families in an effort to strip them of their cultures and language.

- Between 1819 and 1969, the U.S. operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states (or then-territories), including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii.

- Of those 37 states, New Mexico had the third-greatest concentration of facilities, with 43, trailing only Oklahoma and Arizona.

- The schools “deployed systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to attempt to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children through education, including but not limited to the following: (1) renaming Indian children from Indian to English names; (2) cutting hair of Indian children; (3) discouraging or preventing the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages, religions, and cultural practices; and (4) organizing Indian and Native Hawaiian children into units to perform military drills.

- The Federal Indian boarding school system focused on manual labor and vocational skills that left American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian graduates with employment options often irrelevant to the industrial U.S. economy, further disrupting Tribal economies.

Boarding schools in New Mexico got an early start.

Two years after the first boarding school, the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, opened in 1879, the Presbyterian Church opened the Albuquerque Indian School (AIS) for Navajo, Pueblo and Apache students. Later, the school transferred to federal control.

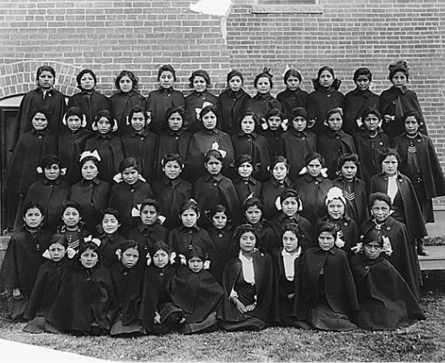

The Albuquerque Indian School merits several mentions in this week’s report, including five photos as I counted them of young Indigenous girls and boys in class, and of the building itself.

I know a few details about AIS. Last year, New Mexico In Depth published a story that revisited the Albuquerque Indian School’s history within the larger context of the boarding school system.

In addition to locating boarding schools across the country, this week’s report identifies at least 53 burial sites for children across this system — “with more site discoveries and data expected as we continue our research.” The authors declined to identify where they are.

One of those burial sites is at the east corner of 4H Park in Albuquerque, a resting place for children and staff at the Albuquerque Indian School from 1882 through 1933. It’s been known in the city for decades. A 1999 study included it in a survey of known cemeteries and burial places across Albuquerque. After a lone marker commemorating the internment went missing, there wasn’t much to mark the burial site, save for makeshift memorials put there by community members. But after the news that a large unmarked burial site was found at a Canadian boarding school last summer, the city started a formal reconciliation process, working with leaders from tribes in the southwest, including Pueblo, Navajo, Apache and others, as well as with people who have a connection to the site.

The Interior Department report features images from other New Mexico boarding schools: Santa Fe Indian School; and in the west, Rehoboth Mission School, Tohatchi and Zuni.

And it describes the forcible removal of Mescalero children, quoting U.S. Indian Agent Fletcher J. Cowart as he described attempts in the 1880s to take Mescalero and Jicarilla Apache children, resistance from chiefs and the tribal nations and his resorting to have Indian police forcibly remove the children from their homes.

“When called upon for children, the chiefs, almost without exception, declared there were none suitable for school in their camps,” Cowart wrote. “Everything in the way of persuasion and argument having failed, it became necessary to visit the camps unexpectedly with a detachment of Indian police, and seize such children as were proper and take them away to school, willing or unwilling. Some hurried their children off to the mountains or hid them away in camp, and the Indian police had to chase and capture them like so many wild rabbits.”

It’s unclear how many Native children went to boarding schools. But the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition estimated “hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families.”

By 1900, “there were 20,000 children in Indian boarding schools, and by 1925 that number had more than tripled,” according to the group. “They suffered physical, sexual, cultural and spiritual abuse and neglect, and experienced treatment that in many cases constituted torture for speaking their Native languages. Many children never returned home and their fates have yet to be accounted for by the U.S. government.”

Marjorie Childress

A sign demands a city council investigation of the circumstances of an unmarked gravesite for Zuni, Navajo, and Apache children who attended the Albuquerque Indian School in the early 20th century. The sign is at a community-built memorial near a burial ground at Albuquerque’s 4-H park.These atrocities were not a secret.

Our story last year highlighted that over the past century government reports sounded the alarm about the boarding schools, beginning with the Meriam Report of 1928, which criticized the schools’ inadequate facilities and the removal of children from their homes. That report stressed repeatedly the need for relevant curriculum adapted to the culture of the children.

Forty years later in 1969, the Kennedy Report came out, sounding more alarms.

The impacts of the boarding schools were profound. This new report describes cultural and familial disruption, and tribal erosion. It references a recent report that studied the physical health of now-adult boarding school attendees’ medical status, finding those who attended boarding schools are more likely to experience chronic physical disease, as well as increased risk for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, depression and unresolved grief.

“The combined direct and indirect results … show American Indians who attended boarding school have lower physical health status … than those who did not,” according to researcher Ursula Running Bear, whose study was paid for by the National Institutes of Health.

Now, in 2022, we have another report.

As I read it, a quarter of the way through this sentence leapt out at me.

“Congress acknowledged that from ‘the beginning, Federal policy toward the Indian was based on the desire to dispossess him of his land. Education policy was a function of our land policy.’ ”

It’s a quote from the Kennedy Report.

Reading those words turned me introspective. I remember, as a young man, on occasion saying “Manifest Destiny” when talking about this country’s history. It’s what I was taught in school in Georgia decades ago.

After living nearly 17 years in New Mexico, where I’ve come face-to-face with the troubling, often horrific history tucked into the shadows by that phrase, I understand more fully the problem of saying “Manifest Destiny” to describe how this country came to stretch from sea to shining sea. I knew about the broken treaties, the removal of entire nations from ancestral lands, the deliberate campaign to rob Native speakers of their languages — the list is long. I’d read about it in books and magazines, seen films and documentaries. But it’s one thing to read about it, removed from the blood and guts of the human toll, and another to see the effects first hand of more than a century of federal policies and discriminatory laws. To hear friends and acquaintances give an alternative telling of the continental expansion that impacted their great-great grandparents and succeeding generations, all the way down to their children — it makes a difference, putting a human face on the stories you read in books.

Living in New Mexico has been part of my educational journey. It’s helped me unlearn what I learned in school. And I want to keep educating myself.

I hope all of us do. But from the political debate of the past few years, where so many seem unwilling to confront uncomfortable truths about this country, I’m unsure whether America is ready to learn this particular history 94 years after the groundbreaking Meriam report

For the sake of all of us, I hope I’m wrong.