Editor’s Note: Joshua Prager is a former senior writer for The Wall Street Journal and the author of “The Echoing Green” and, with Milton Glaser, “100 Years.” His newest book, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, is “The Family Roe: An American Story.” The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Should the Supreme Court overturn Roe v. Wade, as a recent leaked draft opinion indicates it will, it will fall to all 50 states to determine for themselves whether or not to legalize abortion. The general contours of how most will decide is known, and one thing is certain. As the headline of a study by the Center for American Progress put it: “Women of Color Will Lose the Most if Roe v. Wade is Overturned.”

“It’s part of a pattern that women of color would not have access to abortion,” Harriet Washington, author of the book “Medical Apartheid,” told me. “Their rights regarding reproductive health,” she said, “have always been assailed whether by law or by custom.”

That illegalizing abortion will deepen racial inequities is an uncomfortable reality for those who propose doing so. It is no surprise then that, in the run-up to the upcoming Supreme Court decision on abortion, leading pro-life organizations have testified to their own diversity. Those testimonies invariably invoke the same woman: Mildred Fay Jefferson, a pro-life leader and the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School. In the last few months, the National Right to Life Committee honored her, the head of the Susan B. Anthony List wrote of her in an opinion piece and Americans United for Life published a guide to pro-life legislation under an imprint it named for her: Mildred Press.

That Jefferson remains, more than a decade after her 2010 death, a pro-life hero is no surprise. A Black Methodist woman, she embodied the aspirations of a movement that, upon her election in 1975 as president of the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC), was composed almost entirely of White Catholic men.

Jefferson used her perch to mold that movement into a political power that Republicanized opposition to abortion; in response to pressure exerted by the NRLC in the run-up to 1976 presidential election, the GOP, for the first time, addressed abortion in its platform.

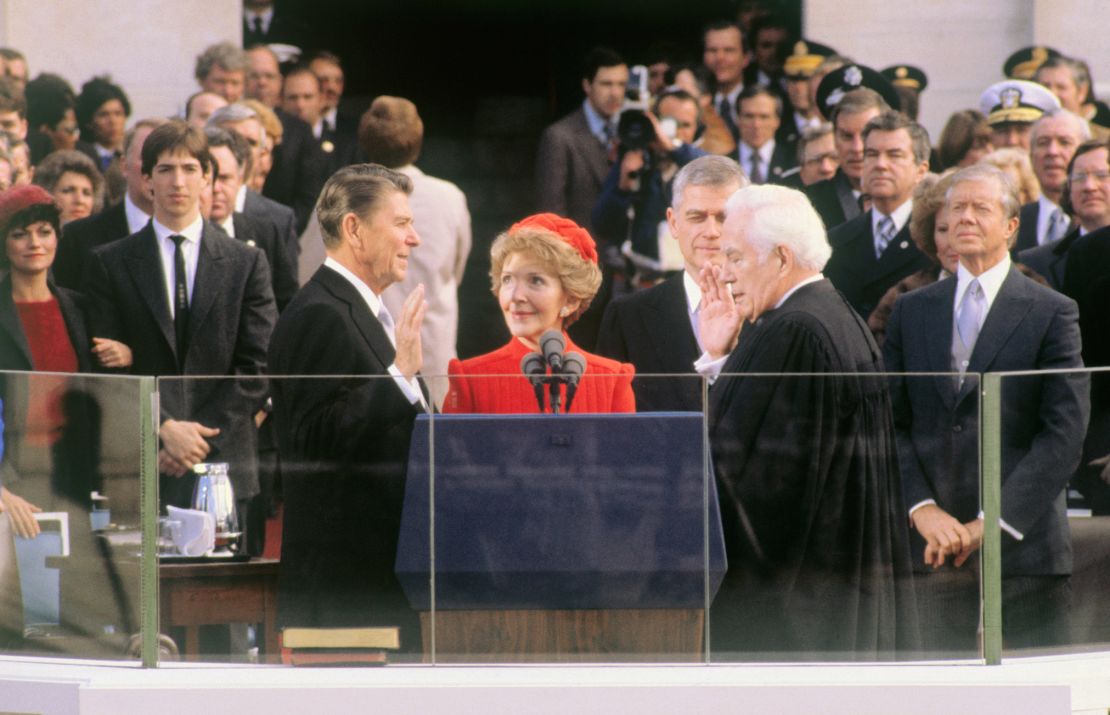

Four years later, the party elected as president someone Jefferson herself had talked into the pro-life fold. As Ronald Reagan, who as governor of California had supported legal abortion, wrote to Jefferson after seeing her on a 1973 TV program: “You made it irrefutably clear that an abortion is the taking of human life.”

Jefferson opposed all abortions. In an article for “Ebony,” she wrote, “You can’t give the individual the private right to kill, no matter what kind of justification they can come up with.” In this, she was less in step with her contemporaries than many of the pro-life leaders of today. She also expressed contempt not only for doctors who provide abortions, but women who have them. “The woman who arranges her life haphazardly, relying on abortion to remove complications,” she wrote months before Roe, “is unworthy of being called woman.”

Jefferson, though, was living a life out of step with her words. And the pro-life movement that claims her today knows almost nothing about her.

Jefferson’s story is remarkable. Born in 1927, the only child of a schoolteacher and pastor, she left segregated Texas and became, at age 24, the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School. She was 43 in 1970 when she left medicine to fight abortion.

A month before the Roe ruling, an appearance on a PBS program called “The Advocates” made her a pro-life star. “I wish I could have heard your views before our legislation was passed,” Ronald Reagan, the governor of California, wrote her on January 17, 1973, referencing a bill he had signed which made abortion legal through the 20th week of pregnancy.

Two years later, Jefferson became president of the National Right to Life Committee, using her perch to transform abortion into political capital that she then helped the Republican party turn into legislation and votes. More, she was helping to grow the pro-life base beyond white Catholic men.

“You know what the best strategy for the pro-life movement would be?” Henry Hyde, a Republican congressman (whose name is synonymous with a federal ban on using Medicaid funds to cover abortion), would tell a pro-life lobbyist. “Someone ought to pay Dr. Mildred Jefferson just to travel around the country and speak out on behalf of the unborn.”

Indeed, Jefferson inspired the movement; she famously wrote that the right to life was not merely for “the perfect, the privileged and the planned.”

But it wasn’t conviction alone that redirected Jefferson from medicine to the fight against abortion. It was prejudice as well. Not until 1968 – 17 years after Jefferson graduated Harvard Medical School – would the American Board of Surgery certify a Black woman, Hughenna Gauntlett. And when, in 1951, Jefferson began her surgical residency at Boston City Hospital, her supervisor, a surgeon named A.J.A. Campbell, told her “she would run into problems… because she was a black female and this may be resented by some of the doctors and nurses.”

Twenty-one years would pass before Jefferson (who had completed the equivalent of three surgical residencies) was at last, in 1972, granted certification. By then, she had begun to fight abortion; in 1970, she co-founded a pro-life organization in Massachusetts.

But she still hoped to realize her lifelong dream of becoming a surgeon, and repeatedly asked the chairman of surgery at her hospital, Richard Egdahl, to refer her patients. Egdahl later acknowledged that he “refused to do so” even though he knew “nothing of a derogatory nature concerning her.”

Devastated, Jefferson left medicine for good. She never spoke publicly of what drove her from medicine, and continued for decades to tell any and all that she remained a practicing surgeon.

Jefferson had experienced racism all her life. The great-granddaughter of slaves (as her cousin told me in an interview), she had had to sit, as a child of five in Texas, in the balcony of the local theater when in 1932 “Little Orphan Annie: came to town. And when, a quarter-century later, on her 30th birthday in 1957, she met a man at a ski lodge in New Hampshire, she was unsure what to do. She came to love him, and wished to marry him.

But the man, a sailor named Shane Cunningham, was White. And while interracial marriage was legal in Massachusetts where she lived, “miscegenation” remained a felony in half of the 48 states. Her life was already difficult; her career was stuck, she struggled with increasing debts and hoarding too. Five years passed before Jefferson finally assented in 1962 to marry the man she loved – but on one condition.

Jefferson had long spoken of the power of self-determination. Achievement, she told the press after graduating from Harvard, was simply “a willing of the right thing to happen.” But, she had come see that determination took one only so far. She had come to believe, as she now told Cunningham, and as he later told me, that to live was to be subject to discrimination, hypocrisy, “extreme unfairness.” She thus resolved, she told Cunningham, to never conceive a child. Cunningham married her with a heavy heart. Jefferson, he told me, “would have been a wonderful mother.”

Jefferson’s decision to not have a child was remarkable for two reasons. First, she believed that propagation was the very purpose of woman – “the essence and reasons we exist as female human beings,” she later told the historian Jennifer Donnally.

Second, her belief that life itself was unjust was at odds with everything she publicly stood for – beginning with the absolute proscription of abortion. It is no surprise that, as the pro-life leader Judie Brown told me, Jefferson lied as to the reason why she had no children, telling friends that she was unable to conceive.

Jefferson’s fight against Roe – and her hoarding, too – left little figurative or actual room for a husband. Cunningham left their home eight years after they married, and the couple divorced eight years after that. Jefferson lived the last decades of her life alone, sustained by a small pro-life non-profit in Tulsa. Having sworn off traditional medicine – doctor checkups and hospitalizations – she died at home in a swell of her papers.

Judie Brown eulogized Jefferson as “the architect of the anti-abortion movement.” The doctor had also experienced extreme racism and misogyny, and within that divide lay the disconnect between what she said in public and what she did in private.

That disconnect makes Jefferson an imperfect symbol for opponents of abortion. But it also makes her an honest one. For as Angela Davis observed, women of color who have abortions speak less of a want to end their pregnancies than “about the miserable social conditions which dissuade them from bringing new lives into the world.”