Last weekend, Derek Matthews, the founder of the Gathering of Nations Pow Wow, asked GOP state lawmaker and GOP gubernatorial hopeful Rebecca Dow to pull a campaign commercial that talked about “critical race theory.

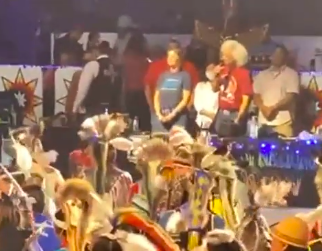

Standing on a stage with Dow in front of thousands of Native people who had flocked to the Albuquerque event from all over North America and beyond after a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic, Matthews’s request hushed the crowd except for a smattering of clapping and whistling.

Dow ignored Matthews and welcomed the Gathering of Nations attendees without responding to his request.

It was an awkward moment.

I want to join Matthews in asking Dow to pull the commercial.

Here’s what I would say if I were standing next to her: Stop talking about critical race theory, Representative Dow. You’re resorting to one of the oldest electoral tricks in American history: Stoking White racial fear to win an election. And you’re doing it by repeating Republican talking points. From my interactions with you over the years, I know you to be better than this.

In the campaign commercial Matthews asked to be pulled, Dow calls critical race theory — which is not taught in New Mexico’s public schools — “racist and Un-American,” part of the “woke agenda” that “radical progressives want. Then she repeats an idea you’re as likely to hear this year in Georgia or Connecticut or Texas by a Republican hopeful running for office: Critical race theory will teach school kids to hate one another.

From everything I’ve read, critical race theory is taught at the collegiate and graduate levels, not in K-12 public schools. And it focuses on how laws, regulations, cultural behavioral patterns and institutions interact over time to create different outcomes for different populations, in health, finances, incarceration rates, etc., not on individual bigotry.

Dow’s commercial appears meant to comfort parents more than their kids. Specifically, to assuage the fears of White adults who are uncertain about how to talk to their kids about race after they learn American history and come to the people they trust most in the world — their parents — to have a genuine, honest conversation.

Talking about race can be uncomfortable. I’ve been on the receiving end of more than a few pointed questions from my own children about growing up in the Deep South.

Dow seems to be saying: I’ll protect you from these uncomfortable conversations, or at least reduce the chances that you’ll have them.

No thank you. I’m more than capable of talking to my children about race and its role in American history.

I’d ask Dow and any other person terrified of critical race theory to read the story of Brittany Murphree, a female law student profiled by Mississippi Today earlier this year after she signed up for “Law 743: Critical Race Theory” as a student at the University of Mississippi Law School.

At one point in the story, Murphree, a young Republican “raised in … one of the most Republican counties in one of the most Republican states,” learns that the Mississippi Legislature is considering legislation that would ban discussion of critical race theory in K-12 schools and universities.

From the story:

The more Murphree thought about the bill, the angrier she got. In just two weeks of taking Law 743, she had been introduced to ideas she never before considered. She learned there were activists and academics who were critical of school integration and the way it had been enforced. She gained a new perspective on racial progress in America. And she still had a whole semester left of issues that no longer felt intimidating but urgent to learn — implicit bias in policing, affirmative action, and reparations.

“Why are they so fearful of people just theorizing and just thinking,” she thought. “We’re not going to turn into, like, communists. Y’all chill out.

Murphree’s reaction to Mississippi legislation ties in with New Mexico.

Dow proudly tells viewers in her commercial that she wrote “the bill to ban (critical race theory) in our schools. To protect kids from radical indoctrination.”

She’s referring to House Bill 91, which was introduced during this year’s legislative session. The two-page bill died a quiet, quick death. Most of the two pages are spent defining what “critical race theory” is. The bill does not lay out a framework for an administrative procedure to identify or police CRT in the state’s public schools so as to root it out. Or set out who is responsible for that vigilance.

The 10 examples the bill uses to define “critical race theory” are versions on a theme — CRT means any theory or ideology that teaches that one race is superior to another or the cause of oppression of another, as if public school teachers are, as I write this, indoctrinating their students en masse, demanding urgent action.

But the greatest number of questions I have surround number seven, which says critical race theory includes instruction that “creates a feeling or feelings of discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological, physical or any other kind of distress in a person on account of the race or gender attributed to that person.”

Where do you even start? How do you measure a feeling? And exactly where on the spectrum of emotion is the threshold for deciding that a particular feeling merits punishment or doesn’t? And who gets to decide? The classroom teacher? The principal? The school board? The Public Education Department?

Does this mean a child who mentions in a classroom discussion the racial discrimination their parents, grandparents, ancestors faced would be sent to the principle’s office? And female students, what about them? Would talking about moments of sexism provoke censure?

Were Dow’s bill to become law, I’m curious how public school teachers would handle teaching about slavery and the Jim Crow era in the Deep South or discrimination against Hispanics and Indigenous peoples in New Mexico — all outcomes of a widespread belief among Anglos in their racial superiority.

So many questions.

Honestly, I feel the same way I did in October when I interviewed a candidate for school board in Rio Rancho, where I live.

I’ve spent most of my adulthood thinking about race and the role it plays in daily life and politics. Partly because from an early age it became clear to me that race influenced most day-to-day interactions in the Georgia of the 60s and 70s where I grew up. But also because, after 30 years of moving around the country, I’ve realized the myth that the South is an outlier on the subject of race is just a fiction White people elsewhere in the country like to tell themselves to feel better.

It was with that conviction and genuine curiosity, that I called him to try to understand why he considered diversity and equity programs and CRT so terrifying, so very racist. It was an unsatisfying conversation. He didn’t help clear up why he believed what he did. He just repeated talking points and acknowledged I had fair points when I posed questions to him, almost as if he’d never considered them before.

Six months after that interview, as the election year is heating up, I still haven’t gotten any closer to understanding why talking about how race and gender shape the world we live in terrifies so many people. And why in the year 2022 stoking White people’s fear is still an effective political strategy.

Honestly, it just feels like I’m back in the Georgia I grew up in so many years ago.