In the period following the explosion begun by Marvel Comics in the 1960s and accelerated by the campy Batman TV series in the middle of the decade, Neal Adams, who has died aged 80 of complications from sepsis, was one of the greatest, and probably most influential, artists in comics. Adams was central to the rethinking of characters including Marvel’s X-Men and, for their rival DC Comics, the Spectre, Deadman and, most crucially, the Batman.

He also brought about changes to business practices, most notably winning artists the right to their original artwork, and getting long-delayed credit and compensation in the 1980s for the Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

“He reinvented the look of comic pages and characters,” said the writer Neil Gaiman. “He was the reason I drew Batman in every school exercise book.” Adams combined the powerful dynamism and expressionist movement of early Marvel’s two masters, Jack Kirby (Fantastic Four, Captain America) and Steve Ditko (Spider Man, Doctor Strange). But his work, influenced by the limitations of four-panel daily comics and glossy ad work, also displayed the more romantic attractiveness usually offered by less dramatic artists. His characters could be as muscular as Frank Frazetta’s barbarians and as appealing as Alex Raymond’s daily strips, but they soared through the panels, every movement telling the story – he was always cinematically aware of the viewer’s place outside the page.

Adams knew early he wanted to draw comics. He was born on Governors Island, New York, where his father, Frank, was stationed with the US army. He grew up on bases, including in Germany, but his father was not heavily involved in his upbringing. His mother, Liliane, worked in a shoe factory and for the national phone company, and ran a boarding house. When his father left, Neal worked on the Coney Island boardwalk, near their home, to help support his mother.

He went to the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design) in Manhattan, leaving in 1959, and then sent his work to DC, who rejected it. When he took it to Archie Comics, the editor Joe Simon (co-creator of Captain America) told him not to ruin his life in the business. Nevertheless, Adams drew sample pages for Archie’s nascent superhero, the Fly, and some of the work was used. He was hired, but to draw comic fillers for Archie’s Joke Book.

After this, he assisted Howard Nostrand, mostly drawing backgrounds on his daily newspaper strip, Bat Masterson, then worked in advertising before getting his own strip in 1962: Ben Casey – like Masterson based on a successful TV series. It ran until 1966. Though daily strips tended to soap opera, Casey, about a hospital surgeon, touched on contemporary issues.

In 1967 he began drawing stories for Creepy and Eerie, black-and-white magazines emulating the 1950s EC horror comics. When DC’s Joe Kubert began drawing the Tales of the Green Beret daily strip, Adams was hired to replace him on DC’s war comics, yet soon found himself working on Jerry Lewis and Bob Hope comics.

But his spectacular cover for The Brave and the Bold featuring Batman and the Spectre led to more work on superheroes, including a remarkable sequence on Deadman. Deadman had been co-created by Carmine Infantino, who was now DC’s publisher. He called Adams his “sparkplug”.

This may explain why Adams was one of the few people to freelance for DC and Marvel simultaneously. In 1969 he and the Marvel writer Roy Thomas tried to revive the failing X-Men book. Their run lasted only nine issues before cancellation, but they brought back Professor X, and when the series was revived in 1975 theirs was the template it followed. Adams, Thomas and the inker Tom Palmer brought The Avengers to new heights with the Kree-Skrull War series (1971-72).

But his key partnership occurred back at DC, with the writer Dennis O’Neil, with whom he had also worked at Marvel. They “recaptured” the Batman from the TV series’ camp “Pow! Wham!” characterisation, creating more realism and more menace, and helping bring the DC line back to relevance. Their new characters, especially the Fu Manchu-like villain Ra’s Al Ghul, who first appeared in 1971, and his femme fatale daughter Talia, and their recreation of the Joker in 1973 as a psychopathic killer, set the bar for future reinterpretations.

They also redid the awkward pairing of Green Lantern and Green Arrow with a story arc including the discovery that the Arrow’s sidekick, Speedy, had become a junkie. Besides having contemporary resonance, it was arguably the first comic storyline to examine the now-familiar paradox of the inability of superheroes to actually change the world.

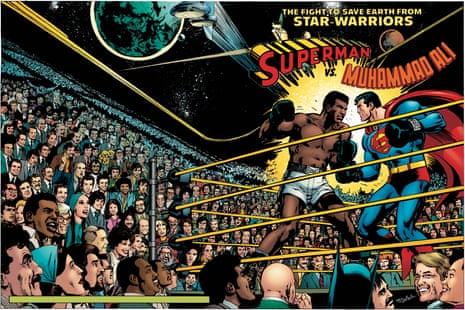

Dissatisfied with both the artistic and economic strictures of comic books, Adams and the DC artist and editor Dick Giordano formed their own studio, Continuity Associates, in 1978. His final story for DC was one of his favourites, Superman Vs Muhammad Ali (1978), with its famous cover containing dozens of celebrities (and colleagues) at ringside.

His company moved in new directions, primarily providing storyboards for movies, but also into animation, game design, computer graphics and advertising. Adams could be a hard teacher, but he was also a supportive resource, whose wide respect in the field opened doors for newcomers. The artists gathered around Continuity Associates also packaged comics for the big companies; they were known as Crusty Bunkers. One of the most famous Bunkers, Denys Cowan, called Adams his “second dad”.

Adams himself illustrated books and worked for some new independent publishers. For years he battled the big companies to establish copyright for artists; in 1987 he won a court decision that denied copyright but compelled the return of original art. Along with the golden age artist Jerry Robinson and the lawyer Ed Priess, he won Siegel, Shuster and their families recognition and royalties from DC just as the Superman franchise was becoming huge.

In 2005, he returned to comics, later writing and drawing the miniseries Batman: Odyssey (2010) for DC and The First X-Men (2013) for Marvel. In 2008, Adams worked with the David S Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, Washington, lobbying the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum to return Dina Babbitt’s original artwork, drawn to illustrate Dr Josef Mengele’s racial theories in order to save herself and her daughter from the gas chambers. He illustrated, with Kubert, a six-page story about Babbitt, with a foreword by Stan Lee; two years later he illustrated and narrated a Disney series, They Spoke Out: American Voices Against the Holocaust.

Adams is survived by his second wife, Marilyn, whom he married in 1987, and their son, Josh, and by his daughters, Kris and Zeea, and sons, Joel and Jason, from his first marriage, to Cory Adams, a comics colourist, which ended in divorce.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion