At a recent Zoom meeting of the Albuquerque Citizens Redistricting Committee, members furrowed their brows and squinted into their computer monitors, examining a newly drafted map that would balance population in each of nine City Council districts.

Member Travis Kellerman, a self-described data-obsessed futurist, had asked the committee’s consultants to find a way to empower voters by dividing the council districts in a way that didn’t pack so many socioeconomically vulnerable residents into two districts in the city’s southern half.

The new concept cut the city’s International District in half vertically, combining each piece with wealthier neighborhoods north of I-40. Residents of the condos around Uptown Mall would be in the same district as a large swath of lower-income southeast neighborhoods.

Members asked longtime consultant Brian Sanderoff for some help interpreting what the changes would mean.

“The International District could end up with two members or zero members [representing them on the Council] and that’s a risk that one takes,” he said. “So you need to ask what’s most important, to preserve the communities of interest or to unpack the socioeconomically vulnerable areas.”

That debate demonstrates the tough choices that face residents and politicians this spring. Months after the New Mexico Citizens Redistricting Committee and the state Legislature wrapped up their work redrawing boundaries for legislative and congressional districts, smaller governmental bodies are tackling the tricky and politically charged task, with mixed results.

Redistricting usually takes place every 10 years, after new Census counts show where population growth has made some districts too big and some too small. A computer algorithm can easily draw districts that balance population, but computers can’t calculate how many residents feel like members of the same neighborhood or sense how they want to organize themselves to have an impact on elections.

Humans must do that. Some local government bodies redraw the maps themselves, others appoint advisory commissions, and some fully assign the task to citizens. Events this year highlight some of the pros and cons of each approach.

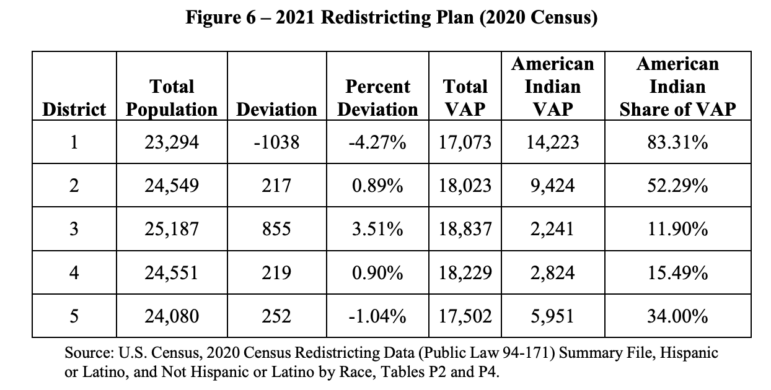

In February the Navajo Nation filed a federal lawsuit against San Juan County, claiming its new plan violates the federal Voting Rights Act with a racial gerrymander designed to limit the impact of Navajo voters.

San Juan County occupies the northwest corner of the state, including a large swath of the Navajo Nation, and Native Americans make up the largest racial or ethnic group, with 41% of the population. According to the lawsuit, County Commissioners selected a new district map last December that created one district with more than 80% of Navajo voters, one district with slightly more than 50% Navajo voters, and the other three with a minority of Navajo voters. The outcome will likely mean, according to the plaintiffs, that Navajo voters will only be able to elect one representative of their choice in the coming decade, rather than the two of five that would more accurately reflect their voting strength.

“The San Juan County Commission chose a map that will significantly divide and lessen the voting power of the largest Sovereign Nation in the United States,” Navajo Nation Council Speaker Seth Damon said in a press release. “The Navajo Nation believes the commissioners have disenfranchised the Native American vote in District 2 and this action does not allow the people to select a leader of their choice.”

A group of civil rights organizations have stepped up to represent the Navajo Nation, including the ACLU of New Mexico, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the UCLA Voting Rights Project. They’re asking the court to order a new plan in which Native American voters have significant influence over at least one more County Commission seat.

The County Commission has so far refused to comment on the lawsuit.

Expensive court cases are not a new facet of redistricting, they’ve been a frequent result of redistricting at the state level. Litigation this year is also happening in Sandoval County, where a group of Democrats in late April sued to have maps redrawn.

Sandoval County is geographically and demographically diverse, encompassing several historic colonial villages, the booming suburb of Rio Rancho—along with three Navajo chapters, part of the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the Pueblos of Cochiti, Jemez, San Felipe, Sandia, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo and Zia.

The county Democratic Party and others claimed that the County Commission’s new plan illegally discriminates against non-white voters. While states are largely left to their own devices by the federal government when it comes to redistricting, the 1965 Voting Rights Act forbids creation of political maps that dilute the voting strength of racial minorities.

Plaintiff and former Sandoval County Treasurer Laura Montoya wrote in an op-ed that the County’s contract demographer, former GOP state Sen. Rod Adair (who also contracted with San Juan County to produce their map options), intentionally packed Native residents into one district whose commissioner would be accountable to 12 separate tribal governments.

“There’s no way to make everybody happy, because it is political in the end, right?” Republican Commissioner Michael Meek told the Rio Rancho Observer. “People are elected to make the decision, and those people told me what they want.”

Others disagree. The failings of the new Sandoval County map highlight the critical need for independent, nonpartisan redistricting committees—at all levels of government,” state Sen. Brenda McKenna, D-Corrales, said in a release.

Just an hour north, that’s already happening.

The city of Santa Fe has had an independent citizen redistricting commission since 2015, after voters amended the city charter. It’s a model good government groups say they love. But apparently the public isn’t as enamored.

In January the city began recruiting volunteers but not enough people applied, so they had to extend the deadline. During that first recruitment round the city didn’t get enough volunteers from two districts, including the one that had grown the most.

And maybe the rules are a little strict. The city charter required that one member of the committee be a geographer or cartographer (the city contracts with outside demographers to actually draw the maps in consultation with the commission members). But no residents with that experience applied so the city had to fill that position with another applicant who didn’t have that skill.

Santa Fe grew by 30% over a decade, according to the most recent Census, when growth in the state overall was close to flat. But that population increase was mostly due to the city annexing more than 13,000 residents early in the last decade. Santa Fe conducted an intermediate redistricting in 2015; and since then the population has only grown about 8%, making a slightly easier job for the committee.

As Santa Fe’s challenges demonstrate, asking for volunteers can pose a challenge, but so does letting politicians appoint members of an advisory committee. The state Legislature’s advisory redistricting committee was formed by collecting three nominations from the state Ethics Commission and four from legislative leaders, who apparently didn’t coordinate the effort.

The seven-member committee they constructed included a former state Senate Democratic majority leader and a former head of the state Republican party, but was widely criticized for including only one woman and not a single Native American member.

The City of Albuquerque uses a similar structure, which some observers say make it vulnerable to political manipulation.

According to the City Charter, members of the City Council must appoint a committee of 18 members, one voting member and one alternative from each district, who will meet and make formal recommendations to the Council.

The councilors named 14 men and four women, who were not as racially and ethnically diverse as the city itself. Some had been active in politics; Some had been former political appointees, staffers for elected officials, candidates for public office or prominent activists.

Like its state counterpart, Albuquerque’s Redistricting Committee serves only an advisory role. The councilors, like state lawmakers, are free to accept, edit or completely scrap the maps they’re sent.

Former state Sen. Sander Rue, a Republican from Albuquerque’s west side, served on the city’s redistricting committee in 2011. He said much of the dynamics are the same at the city and state level.

Although it’s a citizens’ committee and the members aren’t elected officials, they’re vulnerable to political pressures, both overt and subtle.

The makeup of the Albuquerque City Council recently underwent the greatest turnover in the last 20 years, putting new people in four of the nine seats, significantly narrowing the Democrats’ majority and putting a spotlight on the next election.

Huge growth on the city’s west side means that several districts must change significantly. A big question is whether districts should scoop up residents both east and west of the Rio Grande, a river that divides the city, or create districts solely focused on the west side.

Because redistricting happens so infrequently there’s not a lot of institutional knowledge of how it works, beyond the demographers, politicians who have canvassed their districts, and the political consultants who help get them elected.

When Rue was serving on the city redistricting committee, he got a call from a powerful political operative who gave him orders about his participation.

“I screamed at him and told him to f-off, nobody tells me what to do,” said Rue, who had some high-profile clashes with former Republican Gov. Susana Martinez.

At the time Rue felt comfortable bucking orders, although he said he later faced consequences for it.

“There are a lot of people with their fingers in the pot, political parties, different groups within parties, they’ll reach out, they’ll send well-intentioned people carrying their message,” he said, “and these poor people are being bombarded.”

The City of Albuquerque Redistricting Committee will hold its fifth virtual meeting May 4 at 5:30 via Zoom. Information about the process can be found here, where residents may submit comments on the proposed maps. Members of the public may use interactive District software to draw and submit their own maps here.