In the new espionage thriller All the Old Knives, Thandiwe Newton, playing a CIA agent turned posh suburban matron, finds herself in a circumstance many viewers may envy: across the table from a lovestruck Chris Pine, in a near-empty restaurant with a view of the sea at sunset and a seemingly inexhaustible wine list. They order a glass apiece, white for her, red for him. Later on, midway through a dinner that features as many flashbacks as courses, we will see them with five glasses on the table, three on his side, two on hers. It starts to feel like a long time that this pair, former co-workers and lovers, have lingered over their fancy meal. Eventually we figure out that this setup—two middle-aged spies at dinner, engaged in a tense game of cat and mouse as they compare memories of a deadly terrorist incident that took place on their bureau’s watch eight years before—is pretty much going to be the whole movie.

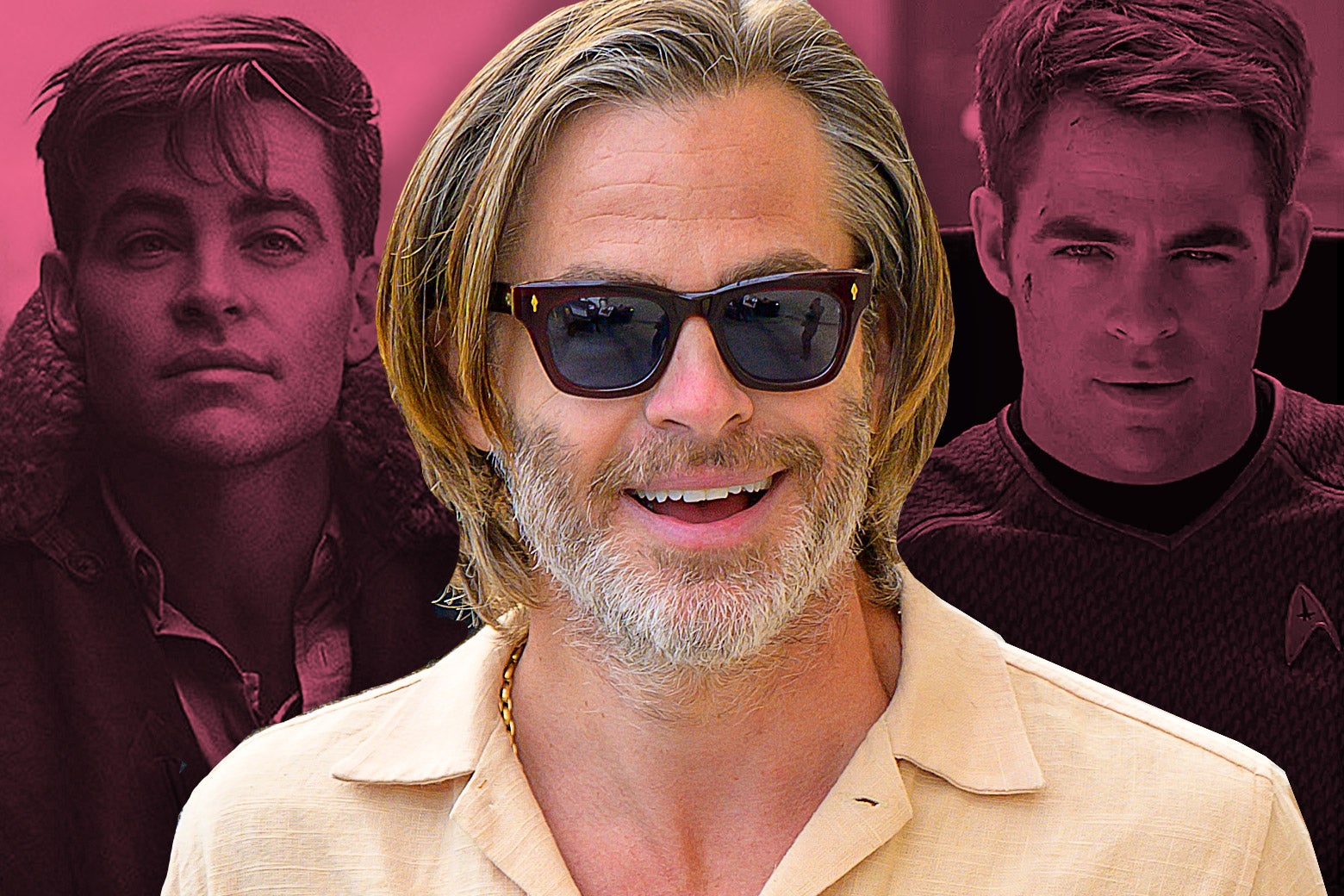

By current action-movie standards, All the Old Knives (the first feature film to be released by Pine’s own production company) is a bit pokey and old-fashioned, with its single location and focus on dialogue and character rather than big action sequences. But despite an unfortunate title that suggests dull-edged kitchen tools more than international subterfuge, this is a satisfying throwback to a type of movie that used to be plentiful on American screens: the midbudget, adult-oriented thriller in which a pair of extremely good-looking movie stars solves a mystery or diplomatic crisis of some kind, while from time to time getting tastefully naked. When movie fans bemoan the way branded franchise content has taken over the big screen, this is one of the disappearing subgenres they’re mourning. Walking out of All the Old Knives, I thought first of Three Days of the Condor, another CIA-set thriller with a central romantic relationship tinged with kink. And as I recalled that 1975 classic (a much better movie to be sure, directed by Sydney Pollack and attuned to the paranoid public mood of the post-Nixon years), another thought soon followed: Maybe Pine is the Robert Redford of our time, which would explain why, working in a very different cinematic culture from the one that made Redford’s career make sense, he has struggled to find the right vehicles for his particular gifts.

Those gifts are less well displayed in another new film, The Contractor, where he plays a returning soldier who, struggling to provide for his family, takes a mercenary job with a private security firm of dubious morality. The result is a taut but slightly underbaked action-adventure movie that has Pine escaping elite teams of killers through underwater tunnels and improvising life-or-death strategies on the fly after the job he is sent to Berlin to do goes south. It’s a Bourne-like tale of intrigue and amorality, but the archetypal Pine persona doesn’t really fit with a Jason Bourne–style character. Any number of actors currently working can carry off the grimly set jaw and stoic competence of the contemporary action hero. Far fewer can, as Pine does in All the Old Knives, tuck into a daintily plated appetizer involving maple-glazed bacon, appear to switch fluently among English, German, and Arabic while interviewing a contact in Vienna, and above all, gaze meaningfully into the eyes of a lost love over a table full of empty wine glasses.

It’s possible I link Pine with wine simply because my first glimpse of the now 41-year-old actor on screen was in a movie about viniculture, the 2008 comedy Bottle Shock—now one of my reliable sick-day comfort watches, both for Pine’s irresistibly buoyant performance as an underachieving “cellar rat” and for Alan Rickman’s sublime turn as a snooty wine merchant reluctantly succumbing to the hedonistic joys of mid-1970s Napa Valley.

In 2009, when Pine had his first high-visibility role as the young James T. Kirk in J.J. Abrams’ cinematic reboot of the original Star Trek series, he was already familiar to me as that guy with the eyebrows from the wine movie. As I wrote in my review of Star Trek at the time, Kirk is in a way a tougher role to take on than Spock, dependent as the original character’s appeal was on William Shatner’s odd mix of comic bluster and melodramatic intensity. And what actor’s line delivery would be easier to simply mimic than Shatner’s trademark staccato speech? But instead of doing a Kirk impression, Pine reinvented the character as a lovably arrogant hothead who is an utterly credible forerunner to the impulsive, womanizing starship captain familiar to us all from reruns. He has since reappeared twice as Kirk, in Star Trek Into Darkness and Star Trek Beyond, and another chapter has long been in the works. The franchise, it might be argued, has offered diminishing returns with each chapter, but Pine’s Kirk never fails to deliver.

It probably doesn’t hurt that Pine’s roots in Hollywood run deep. He grew up in a show-business family going back two generations. His maternal grandmother, Anne Gwynne, was a World War II–era pinup model and actress best remembered for “scream queen” roles in Universal horror films like Black Friday and House of Frankenstein. His father, now 80, has been a working TV actor since the mid-1960s, appearing on the Western series Gunsmoke, the soap opera Days of Our Lives, and most famously the 1980s cop drama CHiPs. Pine’s mother and sister, too, worked as TV and film actors before switching to careers in psychotherapy. Pine, who’s now sometimes trailed by paparazzi asking about his brainy bookstore hauls, earned a degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2002. He happened upon the theater department as a lonely new student seeking his social tribe, and a few years after graduation found himself getting roles like Lord Devereaux, Anne Hathaway’s hunky aristocratic love interest in The Princess Diaries 2: Royal Engagement.

Surveying his filmography over what is now a nearly two-decade career, it’s hard not to notice that Pine has too seldom found roles that take advantage of the qualities that set him apart from many male actors of his generation: a paradoxical mix of boyish enthusiasm (his Steve Trevor in the Wonder Woman movies is a pilot for a reason—Steve really, really loves aviation) and world-weary smarts. Redford in Three Days of the Condor played a professional book reader for the CIA, a character defined by brains rather than brawn; part of the fun of the film is watching what happens when this cerebral desk jockey is called upon to reinvent himself as an action hero. When Pine is lucky, he has found roles that exploit this same brains/brawn tension. His next big role after Star Trek was in Unstoppable, an excellent Tony Scott thriller co-starring Denzel Washington. Pine’s character, a wiseass trainee at the train conductor job Washington’s jaded hero has been doing for 28 years, has something of the cocky energy of his young James Kirk. He’s a smart guy who needs to be taken down a peg or two, and when the two men butt heads as they work together to stop a runaway train, there is buddy-comedy gold amidst the action.

A 2014 attempt at reincarnating Jack Ryan, the Tom Clancy action hero previously played by Harrison Ford, Alec Baldwin, and Ben Affleck, foundered after a single unsuccessful chapter, Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit—a role, and presumably a role choice, Pine later publicly regretted he did not “get right.” In truth, it’s more that the cookie-cutter script didn’t get him right. Pine didn’t find a film role that quite did until 2016, when he appeared in the great Western crime drama Hell or High Water opposite Ben Foster. (The two actors are reunited in The Contractor, and their scenes are the only part of that movie that crackle with dramatic energy.) As the more high-functioning of a pair of bank-robbing brothers, Pine got to play what is probably his meatiest role to date. Around that same time, Pine presented a different side of his performing self when, playing the prince to Anna Kendrick’s Cinderella, he winningly belted the comic duet “Agony” alongside Billy Magnussen in Rob Marshall’s mostly disappointing adaptation of the Stephen Sondheim musical Into the Woods. Pine can sing, as in really sing: In 2016, he duetted with Barbra Streisand on her album Encore, his warm baritone blending beautifully with her familiar trumpet-like soprano as they sang an interweaving medley of “I’ll Be Seeing You” and “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.”

Unlike the three Marvel-affiliated Chrises (Hemsworth, Evans, and Pratt) with whom he is at times misguidedly lumped, Pine has never taken on a superhero role per se. His presence in DC’s Wonder Woman films is, uncharacteristically for a male actor of his physical type, a truly supporting one, as the hyper-uxorious and frequently imperiled boyfriend of Gal Gadot’s Diana. If anything it is Steve Trevor, not Diana, who most often occupies the position of a damsel in distress, requiring everything from deep-sea rescue to magical Themysciran healing waters to, in an unsettling subplot of Wonder Woman 1984, a borrowed human body in which to reincarnate his spirit. In one of WW84’s most charming scenes, Pine even gets a chance to gender-switch the familiar trope of the makeover montage: Transplanted from the World War I era to the year named in the title, Steve models a series of ’80s outfits, offering himself up to the viewers’ gaze in Miami Vice–style jackets and luxuriantly be-zippered parachute pants (“Does everyone parachute now?” asks Steve, ever the aviation nerd) and developing a particular attachment to an American-flag fanny pack. Pine’s recent adoption of ballet lessons as a real-life hobby seems of a piece with the comfort he has always had with the less than stereotypically manly side of himself. He told an interviewer, “I just find [ballet] so beautiful because you have to be so strong and kind of masculine, so to speak, but also very gentle and feminine with your arms and your hands.”

In her “eh, it’s fine” review of The Contractor this week, the New York Times’ Manohla Dargis observes that “Chris Pine often seems too pretty, too nice, decent and, well, intelligent for his movies.” The abundance of pretty is more than fine by me, especially given that as he ages, Pine’s almost comic degree of handsomeness is acquiring a more rumpled, lived-in quality. And though, again like Redford, Pine generally tends to play decent guys rather than villains, I don’t need him to always be nice: In 2015’s Z for Zachariah, he was outstanding as a menacing drifter who disrupts the lives of a man and woman trying to survive in a post-apocalyptic landscape. But the intelligence—that’s the Pine quality that too often remains unexploited, awaiting the kind of scripts not many screenwriters are bothering to write for an industry that no longer makes a place for them.

This summer, Pine is set to start work on his own directorial debut with Poolman, an L.A.-set comic mystery starring Pine himself, Annette Bening, and Danny DeVito. Directing oneself as an actor is a tricky assignment even for someone experienced at both jobs. (Here again, Robert Redford is a case in point.) Maybe watching Pine meet that challenge will show us new depths in an actor who rarely fails to elevate even the most pedestrian material. Imagine what he could do with the kind of freestanding, unfranchised, character-driven stories that make full use not just of an actor’s pretty face (however fine a face it may be: those quizzical dark brows! Those swimming pool–deep eyes!) but of the brain churning busily behind it.