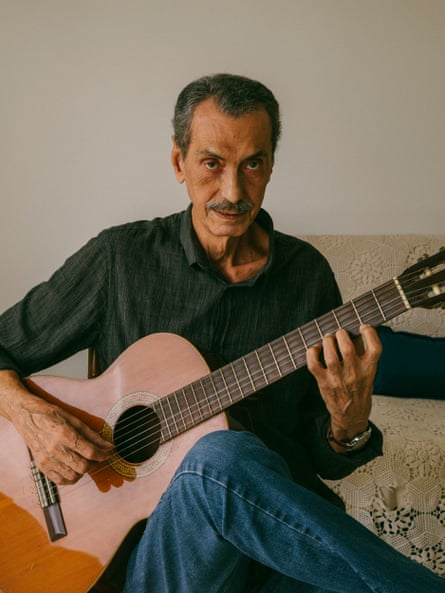

It’s a rainy summer afternoon in Rio de Janeiro and Arthur Verocai is experiencing technical difficulties. The 76-year-old Brazilian maestro is on the phone with his production staff. By the end of the day, he has to print, sign and send a document to Louis Vuitton, which hired him to score its latest show. Only then will he get paid. The courier is already en route. But the printer is not working. And Verocai, tense, can’t find a pen. “I hate these bureaucracies,” he says, as he paces his spacious apartment in the city’s south zone.

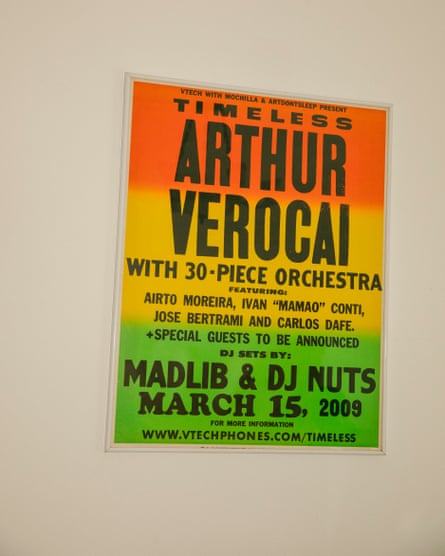

When the printer finally complies and the document is handed off, Verocai scratches his grey moustache, flops his tall, skinny body on the living room sofa, picks up his guitar and tells the photographer: “I swear I don’t understand why you want to take my picture. I am not that important.” A picture on the wall of his living room tells a different story. It’s a poster from a Verocai concert in Los Angeles, in March 2009, backed by a 30-piece orchestra, with guests such as drummer Ivan “Mamao” Conti, the late keyboardist José Bertrami (both from the samba jazz fusion group Azymuth) and the percussionist Airto Moreira, and supporting DJ set by Madlib. “That was one of the best shows LA has ever seen,” the producer Cut Chemist told NPR.

That night was the first time Verocai played his self-titled debut album live and in full. Originally released in 1972, when Brazil was under military dictatorship, it offered a unique mix of jazz, funk, soul, samba and bossa nova, and showcased Verocai’s sublime orchestral arrangements, which had previously seen him work as an arranger with the likes of Jorge Ben. But the album vanished quickly, under-promoted by his label, Continental Records, and ignored by critics.

Disillusioned, Verocai abandoned his short-lived music career. “I started to think it was crazy to have made a record like that back then,” he says. “After all, I was an arranger and nobody cared about arrangers making records.” (His plight, in that sense, mirrors that of Beach Boys arranger Van Dyke Parks, whose early solo albums were notorious commercial flops.) He moved on to advertising. “I went to work with jingles – ads for everything from trucks to cat food. The cash was good, but I knew that no one in that environment was interested in the music I made. I think that’s why I ended up staying there. I wanted to run away from myself.”

The album Arthur Verocai went out of print and disappeared from stores, and its author continued to arrange for other artists, although less and less frequently. But gradually, the album’s legend grew among collectors and DJs. Decades later, a copy of the original was sold for $2,000. In 2003, the 29-minute masterpiece was rereleased by US label Luv N’ Haight Records. That’s how hip-hop artists such as Ludacris, MF Doom and Little Brother discovered it, sampling its tracks and making the album and its author into a cult concern.

That sold-out show in Los Angeles was billed under the name Timeless, and filmed for a DVD release directed by Brian Cross. “To be there was very moving,” says Cross. “It felt like the force of what had been done in 1972 in Rio took on a new set of legs. Arthur felt it, Mamao, Airto, Bertrami all felt it. They were like a group of elite players moving together. MF Doom introduced Arthur that night, which was wild as Arthur had no idea [who he was]. We knew something was liberated in the air that night that truly could help people hear the genius of what he had done.”

It helped Verocai, too: it was the first time he had heard the songs from his debut realised in the way that he had imagined them. “I hadn’t heard that record again for years,” he says.

In the 1960s, Verocai was a student of civil engineering. He graduated in 1968, “but didn’t work much in the field”, he says. “Instead, I chose to build music.” He had begun playing bossa nova at six years old, and later studied under Roberto Menescal, a legend of the genre. He got his first break as an arranger aged 21 – for the Brazilian singer Leny Andrade – after being spotted showcasing his work at music festivals, and was soon in high demand. Writing his self-titled album alongside lyricist Vitor Martins offered him freedom compared with working for other artists and to fulfil commercial briefs – although freedom was conditional given the country’s military rule.

“It was made during tough times in Brazil, when many lyrics were censored by the dictatorship,” says Verocai. “So, to avoid problems, Vitor had to use a lot of metaphors in the lyrics. [The song title] Presente de Grego [Greek Gift] meant that the dictatorship was a Trojan horse to Brazil, a bad gift. And Pelas Sombras [Under the Shadows] was about the way the government secret police acted in the shadows, hidden from public, getting people arrested. It was like camouflaging our feelings. But for me, I just wanted to make the best music I could.” It all came together, he says, when he got into the studio with some of the best Brazilian musicians of the 70s – Paulo Moura, Nivaldo Ornelas, Hélio Delmiro and Oberdan Magalhães. He met his own ambitions, he says, “but nobody noticed back then. So that show in Los Angeles brought an incredible feeling of deep satisfaction.”

The revival of his work prompted Verocai to make more music. In 2002, he independently released the album Saudade Demais, followed five years later by Encore on London label Far Out Recordings. In 2016, the album No Voo Do Urubu (for Japanese label Kissing Fish, later reissued by Light in the Attic) featured guests such as Seu Jorge and Mano Brown and was released to lavish national acclaim. That year, he also made the music for the closing ceremony of the Rio 2016 Paralympic Games.

“I’ve never seen anyone like Verocai,” says Menescal. “He always did his job with discretion, moving forward, sometimes without anyone knowing. Many times, I came to think that he had abandoned everything. But, of course, he hadn’t.”

In Rio, it is still raining. Verocai takes me to the kitchen to make some coffee. He says this apartment is too big for him. “I remarried in October last year and we moved here. But unfortunately we split up a month later and I ended up alone in this huge place. On second thoughts, maybe it was a mistake. I guess I’m too old for these adventures.”

But not musically. His recent activity is adventurous and connects the dots between Verocai and the artists he has influenced. In January, he did the stunning arrangement of Tyler, the Creator’s score for designer Virgil Abloh’s posthumous show for Louis Vuitton at Paris fashion week. Verocai recently worked on Brazilian samba superstar Marisa Monte’s latest album, collaborated with the Australian jazz-funk band Hiatus Kaiyote – who contrived a mini-tour to Brazil in 2019 just to meet Verocai in person and record a song for their 2021 album Mood Valiant – and arranged four new songs by Canadian fusion group BadBadNotGood for the album Talk Memory.

Up next are collaborations with Flor Jorge, daughter of Seu Jorge, and Zeca Veloso, the youngest son of Caetano Veloso, and with one of music’s most mysterious stars, though he’s not at liberty to say who. “I signed a confidentiality agreement,” he says, lowering his voice.

There’s also more new solo music. Verocai opens his computer and plays me some new songs for his next studio album, scheduled for release next year. As we listen, he occasionally accompanies the recordings on guitar. Truira and Ajuste de Contas are gorgeous and uplifting, while Bilheteiro has the funky jazz flavour of Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters.

Verocai will perform his 1972 album again in São Paulo later this year to celebrate its 50th anniversary. “I’ll invite some guests, it will be a good party,” he says. There will be a live album, as well as a documentary for Brazilian television. “The idea is to pay tribute to Verocai, a genius still underestimated in his own country,” says director Leonardo Fiorito. “But we don’t want to be limited to the 1972 record. We want to show how he is still active today, still touching people.”

BadBadNotGood drummer Alex Sowinski is one of them. He says he’ll never forget the first time he heard the music Verocai wrote for their song City of Mirrors. “I had to go back and play it again and again to start to comprehend what I was hearing. It’s spicy, alive and creates emotion that reaches the soul.”

“Wow,” says Verocai when I tell him what Sowinski said. “Did he really say that? It makes me feel so good. It’s so refreshing to work with the new generations. That’s what keeps me moving forward.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion