Abstract

Carangids are abundant and commercially important marine fish that contribute to a significant portion of the fisheries in many parts of the world. In the present study, we characterized the complete mitogenome of the Indian scad, Decapterus russelli and performed a comprehensive comparative mitogenomic analysis of the family Carangidae. The comparative mitogenomics provided valuable insights into the structure, variability, and features of the coding and non-coding regions that evolved across species over millions of years. The structural features of tRNAs revealed changes in the frequency of mismatched and wobble base pairs, which is reflected in the base composition of H and L strands. The highly conserved sequence motif of the mTERF binding site in carangids over the ~ 400 MYA of their divergence demonstrated the functional importance of these sites. The control region of carangids was characterized by the presence of discontinuous repeat units with a high rate of sequence divergence in the form of base substitutions, insertions, and deletions. The maintenance of secondary structures in the control region independent of the rapid evolution of primary structure suggested the effect of selective constraints on their maintenance. Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) phylogeny revealed a similar topology consistent with previous taxonomic studies. The extant carangids diverged through the evolutionary events experienced during the Cretaceous, Paleogene, and Neogene periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The carangids represent an important group of exploited pelagic coastal resources of the world with diverse morphological features comprising approximately 147 species1. They occupy a variety of habitats consisting of pelagic, benthopelagic and reef-associated regions in all tropical and subtropical seas2,3. Currently, 4 subfamilies are recognized within the Carangidae4. Annual global capture production of Carangidae was estimated at 5.13 million tons in 2018, 65% of which came from Asia (https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/statistics). Among the carangids, one of the commercially most important species is the Indian scad, D. russelli (Ruppell, 1830), providing a cheap source of animal protein. It is also commonly used as live fish bait5. It is widespread in the Indo-Pacific and forms an important fishery resource in India and Southeast Asia6. Most studies on carangids have focused on biology, ecology, and taxonomy7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, and it is important to study the genetic and genomic traits to resolve taxonomic ambiguities, understand evolutionary traits, and implement conservation strategies.

The vertebrate mitochondrial genome, which plays a crucial role in cell metabolism and organism function, is ~ 15–20 kb in size and consists of 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes and a non-coding region (control region)19. The PCGs, tRNA and rRNA have a relatively low mutation rate because they are subject to strong purifying selection20. In contrast, the control region evolves at a high rate compared to the other parts of the mitogenome, and these high rates of sequence divergence are mostly localized in the variable flanking region, which is adjacent to the conserved sequence motifs21,22,23.The extensive comparative studies in fish24 have demonstrated the ability of the control region to form stable secondary structures and the existence of selective constraints for their maintenance. Although Zhu et al.25 analyzed the phylogenetic relationships of carangids using the control region, there is a gap in knowledge regarding the mutational pattern and the non-random distribution of these mutations between the conserved motifs and their flanking regions. There is also a lack of knowledge about the structure and variability of tRNA genes in carangids and the frequency of occurrence of G-U wobble base pairs, the fundamental building block of RNA structure critical for RNA function in various biological systems.

The phylogenetic relatedness between the carangids has been extensively studied using comparative morphological4,26,27,28,29,30,31 and molecular tools32,33,34,35,36,37. Although there has been a discourse on monophyly4,28,29,30,31 vs. paraphyly36,37 of carangids, the congruent topologies of phylogenetic trees constructed using DNA sequences suggested paraphyly of carangids if Echeneoids were not included35,36,37,38. Carangids can be considered as promising candidates for evolutionary studies, as they have a wide diversity in terms of habitat (marine, brackish water, freshwater), morphology (having variable body size; less than 20 cm to ~ 2 m), and shape (deep-bodied, streamlined). Some species of remoras live even as commensals on large pelagic vertebrates39. The phylogeographic study inferred from nuclear gene supermatrix suggested a terminal cretaceous crown age for carangids with major lineages diversifying during the Paleogene36. A late Eocene age has also been proposed for the crown carangids35. But densely sampled molecular studies indicated a Cenomanian stem age of the Carangoids which had undergone a significant diversification during the late cretaceous37,38. The subfamily Naucratinae originated early in the Paleocene40, Trachinotinae date back to the early Oligocene and the remaining Carangoid lineages including the morphologically heterogeneous group, Caranginae comprising the genus Decapterus appear to have originated during the middle Eocene38. The genus Decapterus originated in the upper Miocene41. The genetic distance between the genus Decapterus was significantly greater than that between Trachurus42, suggesting that Decapterus arose long before its sister group Trachurus, making them the most divergent species group. The morphology of the genus Decapterus includes multiple forms such as long-bodied, cylindrical, mackerel-like with a small mouth, reduced teeth and reduced scutes on the straight part of the lateral line, suggesting adaptations to the wide ranging off-shore life43.

In the present study, we report the complete mitogenome of D. russelli for the first time elucidating the special characteristics. Although recent studies have examined the evolutionary history of carangids44, we reanalyzed the patterns by including mitogenomes from 37 species and describing the relationships and evolutionary patterns among species with a robust phylogenetic tree. We also performed a comprehensive comparative analysis of carangid mitogenomes especially the mutational patterns of coding and non-coding regions, control region secondary structure, and structural features of tRNA to gain insights into the evolutionary dynamics of mitochondrial DNA.

Results and discussion

Mitochondrial genome organization and composition

The total length of the mitochondrial genome of D. russelli was 16,542 bp. The genome organization is congruent with that observed in other teleost fishes with a standard set of 13 putative PCGs, 22 tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes, and a control region. All genes were encoded on the heavy strand (H) except for the ND6 and 8 tRNA genes which were encoded on the light strand (L) (Supplementary Fig. S1). A similar gene arrangement was observed in other Carangidae species studied (Supplementary Table S1). The overall nucleotide composition of D. russelli mitochondrial genome was 27.5% A, 30.2% C, 25.4% T, and 16.9% G. The AT and GC skew values of the whole mitogenome were 0.039 and − 0.028 respectively.

The results suggested that A and C are predominant base constituents than T and G, with the overall nucleotide composition being severely C-skewed. These results agree well with their respective counterparts in other Decapterus spp.45,46,47 The bias against G was presented following the results reported previously in other teleosts48,49. The AT-/GC- skew values of other Carangidae species were also determined (Supplementary Table S2). The sequence of the complete mitogenome of D. russelli has been deposited with NCBI, GenBank with the accession number MN711693.

Overlapping and Intergenic spacer regions

Seven gene overlapping regions ranging from 1–7 bp and 11 spacer regions varying in length from 1 to 38 bp were detected in the D. russelli mitogenome with the longest intergenic spacer region observed between tRNA Asn and tRNA Cys. Significant differences in the number and length of both the intergenic spacer region and the overlapping gene regions were observed in carangids (Supplementary Table S3). The number of spacer and overlapping gene regions varied between 10–12 and 6–15, respectively, between species. The intergenic spacer is distributed over 11 regions in almost all carangid species studied so far. However, an additional spacer region was observed in C. armatus (tRNA-His-tRNA-Ser (GCT)), E. bipinnulata (ND6-tRNA-Glu), G. speciosus (tRNA-Val-16SrRNA), P. niger (16SrRNA-tRNA-Leu (TAA)), S. crumenophthalmus (ND6-tRNA Glu) and S. dumerili (ND6-tRNA Glu). In addition, the spacer region found between tRNA-Arg and ND4L in all species was absent in Seriola spp, S. nigrofasciata, T. carolinus and T. ovatus. Besides, C. equula and P. dentex lacked a spacer region found between ND1 and tRNA-Ile which was present in all other taxa. A comparative analysis among 37 carangids revealed that the longest spacer (42 bp) occurred between tRNA-Asn and tRNA-Cys of T. carolinus. Seven regions of overlapping gene regions were observed in most carangids, with the longest overlapping region being between ATP8 and ATP6 in some species and between ND4L and ND4 in others.

Protein Coding Genes (PCGs)

The total length of PCGs in the D. russelli mitogenome was 11,425 bp, ranging in size from 165 bp (ATP8) to 1839 bp (ND5) accounting for 69% of the entire genome. GC skew values of all PCGs were negative except for the case with the L-strand encoded gene, ND6, which was greater than zero (Table 1). Similarly, the majority of PCGs had negative AT skew values. These results suggested that the bases C and T are over-represented in most PCGs. The base skew values for PCGs of the other 36 carangid species are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The GC and AT skew values of all were negative, except the AT skew value for M. cordyla and C. tille which was positive. Besides, T. ovatus was presented with equal numbers of A and T in PCGs, a trend not observed in other carangids.

The initiation and termination codons in D. russelli were confirmed by aligning the corresponding genes to other carangids. Among the 13 PCGs, 12 of them shared the same orthodox initiation codon, ATG, whereas COI had a different initiation codon and started with GTG instead of ATG (Table 1). Besides, 6 genes exhibited incomplete termination codons, either TA (COIII) or T (ND2, COII, ND3, ND4, and Cyt-b). The remaining genes revealed complete stop codons in open reading frames either TAA (ND1, COI, ATP6, and ND4L) or TAG (ATP8, ND5, and ND6). The incomplete codons can be completed by polyadenylation of the messenger RNA after cleavage50,51. Comparative analysis among carangids revealed that most PCGs started with the ATN initiation codon (Supplementary Table S4). COI of all the species started with GTG except ATC in G. speciosus. All other PCGs start with ATG except ATA for ATP6 (A. djedaba, A. kleinii, A. mate, C. ignobilis, C. melampygus, C. equula, C. tille and M. cordyla) and ND4L (T. trachurus), and GTG for ND5 (T. blochii, T. carolinus and T. ovatus).

We observed that the value of Ka was significantly smaller than Ks in all 13 PCGs on analyzing the evolutionary rate of PCGs. This indicates that there is a much lesser chance for a mutation to be different between species that can modify the amino acid sequences of a protein sufficiently to change its function than one which is silent52. The average Ka/Ks ratios substantially differed among PCGs indicating varying functional constraints experienced by individual genes (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Table S5). The fundamental features of genome evolution were largely determined by the influence of two non-adaptive forces, mutation pressure and genetic drift53. Nevertheless, the deleterious effect of mutation is very difficult to establish under purifying selection54. In PCGs, the average Ka/Ks ratio varied from 0.008 in COI to 0.469 in ATP8. Altogether the results indicated that the functional genes of carangids have undergone strong purifying selection to eliminate deleterious mutations thus maintaining the protein structure.

We estimated the degree of mitochondrial gene conservation by assessing the total p-genetic distance between 37 Carangidae species (Supplementary Fig. S3). In our analysis, we obtained the highest overall p genetic distance for the ATP8 gene (0.301) and the lowest value for the COI gene (0.019) based on the data of the first and second nucleotide position of codons. The same trend was also observed in the values discerned from the full-length comparison of each gene, with ATP8 and COI represented by a total p-genetic distance value of 0.390 and 0.134, respectively. Based on these results it could be inferred that gene, ATP8 has the fastest evolutionary rate among Carangidae and COI the slowest. Besides, all genes had overall high p-genetic distance values for wobble nucleotide position, ranging from 0.393 to 0.564. This result was consistent with previous reports in other fish species that most of the differences occurred at the 3rd codon position of PCGs in mtDNA55.

Codon usage analysis

A total of 3800 amino acids of PCGs are encoded in the mitogenome of D. russelli. The codon usage patterns are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4A. The amino acid Leu was represented by six different codons and the rest of them by either four or two. The amino acids Leu (16.46), Ala (8.75), and Thr (7.96) were most abundant in the D. russelli mitogenome. Among these, the frequency of Leu (CUC, CUA), Ala (GCC), and Thr (ACC) was highest. The frequencies of stop (UAG), Cys (UGU), and Arg (CGG) in PCGs were lowest. A comparative analysis showed that the codons ending in A or C occurred most frequently in amino acids with sixfold and fourfold degenerate third positions in Carangidae. In a two-fold degenerate codon, C was used more frequently than T. Consistent with the overall bias against G56, it was the least common wobble position nucleotide in all categories. However, analysis of relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) showed that the codons UCC for Ser, CUC and CUA for Leu and GCC for Ala occurred most frequently, while UUG for Leu, AGU for Ser and GCG for Ala were rare in the mitogenome of Carangidae (Supplementary Fig. S4B). It was also inferred from the RSCU value that the synonymous codons NNA and NNC were in the majority than the codons NNT and NNG (Supplementary Table S6).

Transfer RNAs and ribosomal RNAs

The mitogenome of D. russelli contained 22 tRNA genes typical of the metazoan mitogenome. In total, the tRNA genes contributed 1555 bp to the entire genome, which ranged from 67 bp (tRNA-Cys) to 74 bp (tRNA-Lys (TAA)). The secondary structure of tRNA genes predicted by ARWEN57 makes it clear that all tRNAs could be folded into a canonical cloverleaf structure, with the exception of tRNA-Ser (GCT), in which no recognizable dihydrouridine (DHU) stem was found (Supplementary Fig. S5). Comparative analysis with other carangids revealed that the total length of tRNAs varied from 1548 (S. rivoliana and E. bipinnulata) to 1564 (T. blochii). The overall A + T content was estimated at 54.2%. Base skew analysis of 22 concatenated tRNA genes (Supplementary Table S2 revealed a positive AT skew (0.125) and a negative GC skew (− 0.098). The comparisons showed that the AT skew varied from 0.105 (S. nigrofasciata) to 0.224 (T. ovatus) and the GC skew varied from -0.120 (S. rivoliana) to − 0.091 (T. carolinus). The anticodons of these 22 tRNA genes were identical to those reported in other carangids (Supplementary Table S7). Despite the general one-to-one codon-anticodon correspondence, tRNA genes for Ser (TGA and GCT) and Leu (TAA and TAG) have been determined by two types of anticodons. Furthermore, G-U mismatches were observed for 16 of the tRNAs in their respective secondary structures (Supplementary Fig. S5). Five of the tRNA genes appeared to have A-C mismatches (tRNA-Val (TAC), tRNA-Leu (TAA), tRNA-Ile (GAT), tRNA-Arg (TCG), tRNA-His (GTG) in their respective amino acid acceptor stems. Similarly, two A-A mismatches, each for tRNA-Phe (GAA) and tRNA-Ser (GCT) and two C–C mismatches each for tRNA-Leu (TAG) and tRNA-Thr (TGT) were also detected. The presence of unmatched base pairs in mitochondrial tRNAs appeared to be a general trend that can later be repaired by post-transcriptional editing mechanisms prevalent in vertebrate mtDNA58.

Two rRNA genes, a small (12 s rRNA) and a large (16 s RNA) subunit were located in the H strand of D. russelli. The total length of two concatenated rRNA genes was estimated to be 2677 bp with an A + T content of 53.7% (Supplementary Table S2). The AT content of the 12S rRNA gene was 52.2% with a positive AT skew of 0.172 and a negative GC skew of − 0.079. Similarly, the AT content of the 16S rRNA gene was 54.4% with a positive AT skew (0.191) and a negative GC skew (− 0.116). Moreover, the presence of a higher proportion of A and C bases in rRNA genes indicates an AC-rich trend, consistent with previous reports from other teleosts53,59,60. Consistent with previously reported results from other mitochondrial genomes61,62,63, these two rRNA genes were positioned between tRNA-Phe and tRNA- Leu (TAA) separated by tRNA-Val. Comparative analysis among carangids (Supplementary Fig. S6) indicated that the length of two concatenated rRNA genes varied from 2655 bp (G. speciosus) to 2683 bp (A. kleinii). The AT skew varied from 0.1615 to 0.2256 and the GC skew varied from − 0.124 to − 0.077 (Supplementary Table S2).

Features of tRNAs

Secondary structure

The comparative analysis of 37 carangids revealed that most of the tRNAs are structurally different in both the stem and the loop. However, 2 tRNA genes, tRNA-Trp, and tRNA-Leu (TAG) exhibited similarities in their secondary structure (Fig. 1). As can be seen from Table 2, length variation was detected in all four stems. The anticodon stem (AC stem) of all the tRNAs was 5 bp, except for tRNA-Ser (GCT), which displayed length variation (5 or 6 bp). Though the pseudouridine (TΨU) stem of most tRNAs was 5 bp, tRNA-Phe (4 bp), tRNA-Met (4 or 5 bp), tRNA-Lys (4 bp), and tRNA-Ser (GCT) (6 bp) indicated length variation. In the acceptor stem (AA stem), tRNA-Ser (TGA) displayed a length of 6 bp, and the rest of the tRNAs showed more of a length variation of either 7 bp or a range of 7 to 8 bp. Although the DHU stem was mostly 4 bp in length with a range of 3 to 5 bp, tRNA-Ser (GCT) of all carangids examined had only a small loop with no stem.

Secondary structure of tRNAs showing structural variations in 37 species. The first structure represents the nucleotide positions common to all tRNAs (1–88) and details of stem- loop. Length variations in stems and loops are indicated by grey squares and green arcs respectively. The secondary structure of tRNAs were predicted by ARWEN software (http://130.235.244.92/ARWEN/) and edited manually in Adobe Photoshop CS6.0.

Of the four loops, the length of the AC loop was fixed (4 nucleotides), whereas the remaining three loops showed considerable variation in length. Of these, the DHU loop was extremely variable, ranging from 3–13 nucleotides. Conversely, the variable loop (V loop), mostly 4 nucleotides with a range of 3–5, and T ΨU loop, mostly 7 nucleotides with a range of 6–9 displayed the least variation.

Wobble base pairs in the stem regions

The wobble base pair is a unique feature of RNA structure and their often high evolutionary conservation64 underscores their functional and structural importance. Due to its thermodynamic stability, the G-U often substitutes G-C or A-U base pairs and it differs from Watson–Crick and other mismatched base pairs owing to its structural, conformational, and functional properties65. Diverse proteins and other ligands specifically targeting tRNA exploit these features66 and thus the comparative analysis of tRNAs is very crucial for understanding the structural and functional features of the mitogenome. Supplementary Table S8 illustrates the frequencies of Watson–Crick and Wobble pairing at each of the 25 base pair sites of each tRNA in 37 carangids (8 in AA stem + 5 in DHU stem + 6 in AC stem + 6 in TΨU stem). Seven sites from each stem (1–87, 2–86 and 8–80 base pair sites in the AA stem, 12–32 and 15–30 in the DHU stem, 40–48 in the AC stem, and 64–74 in the TΨU stem) revealed a high rate of (100%) Watson–Crick and Wobble base pairing (hydrogen bonding) and these sites may play a pivotal role in maintaining stem structure. Among the tRNAs, tRNA-Ala, tRNA-Asn, tRNA-Cys, tRNA-Ser (TGA), tRNA-Asp, and tRNA-Pro had a higher frequency (≥ 98% overall average) of hydrogen bonding than other tRNAs. Moreover, L strand-encoding tRNAs exhibited, on average, a higher frequency of hydrogen bonding (97.48%) than H strand encoding tRNAs (94.78%).

Table 3 shows the number of G-U wobble base pairs in each stem of 22 tRNAs for the 37 carangid species. Individual stems and tRNAs rather displayed considerable variations in the frequency of GU base pairs, 6% of the base pairs comprised of wobble base pairs on average in the four stems of mitochondrial tRNA with a large difference between stems (4.57% in the TΨU stem and 12.26% in the DHU stem). A substantial difference was also discerned between the tRNAs (0.72% in tRNA-Ile versus 19% in tRNA-Glu) with no wobble base pairs observed in the case of tRNA-Lys and tRNA-Leu (TAG). Furthermore, the tRNAs encoded by different strands exhibited a significant difference in the frequency of wobble base pairs, as the L- strand encoded tRNAs had a higher frequency of wobble base pairs (13.18%) than those of H- strand encoded tRNAs (3%) (Mann–Whitney U test, p < 0.01).

Mitochondrial transcription termination factor (mTERF) binding site

We compared tRNA-Leu (TAA) which has been reported to contain the target binding site for mTERF in humans67 to identify its presence in Carangidae. An important tridecameric sequence (5'TGGCAGAGCCCGG3') reported in the human mitochondrial tRNA-Leu (TAA) gene48,49 was also identified in Carangidae in the same region as the corresponding part of their DHU arm. The mTERF binds to this site with high affinity and regulates the level of transcription from the rRNA genes into the remaining genes of the major coding strand50.

All bases in the 13 nucleotide positions identified in 37 carangid taxa were completely identical to those in humans (Supplementary Fig. S7), suggesting that this site in carangids may follow the same mechanism of function as proposed for humans.

Control region: mutational patterns and secondary structure

The control region of D. russelli was shorter than other carangids, consisting of 840 bp flanked by tRNA-Pro and tRNA-Phe on either side. The control region comprised the highest A + T content (63.6%) compared to other regions of the mitogenome (Supplementary Table S2). AT skew was positive (0.038) and GC skew was negative (− 0.104). Considerable variation was observed in the AT and GC skew values of other carangids, ranging from − 0.047 (S. crumenophthalmus) to 0.065 (T. blochii) and − 0.278 (C. ignobilis) to − 0.093 (D. maruadsi), respectively. The composition of the nucleotide adenine (A) is higher than that of thymine (T) in D. russelli compared to other carangids (Supplementary Table S2). However, the control region of A. mate, A. djedaba, C. ignobilis, G. speciosus, and T. blochii possess a slightly higher percentage of adenine (A) than that of D. russelli. Besides, the composition of thymine (T) is higher than adenine (A) in C. armatus, C. malabaricus, C. tille, C. melampygus, T. japonicas, S. crumenophthalmus, S. dumerili, and S. lalandi. The GC skew of all the carangids was negative. It was found that the maximum length variation for the control region was observed in the range of 840 bp (D. russelli) to 904 bp (S. crumenophthalmus) in the carangids examined. Among the carangids, S. crumenophthalmus possessed the longest mitogenome, and S. rivoliana and S. dumerili were determined to have the shortest mitogenome. It was evident that these species do not exhibit any notable variation with respect to their PCGs, tRNA and rRNA (Supplementary Fig. S6), hence the 61–62 bp variation in the control region alone contributed to the difference in their overall mitogenome length. The majority of the primary sequences of the control region are presumed to be not involved in regulatory function as this region shows great variation even among closely related species68.

Comparative mitogenomics of carangids revealed high variability in the mitochondrial control region due to length variations and the accumulation of base substitutions and indels. Consistent with the recognition sites in many marine fish69 we have detected the 3 central conserved sequence blocks (CSB- F, CSB- E, and CSB-D) and 3 conserved sequence blocks (CSB- 1, CSB-2, and CSB- 3) in all taxa. Palindromic sequence motifs—'TACAT' and 'ATGTA' were found in multiple copies distributed towards the 5' end of the control region [Fig. 2; Supplementary Table S9] and are believed to act as the termination site of heavy strand replication69. The segment corresponding to Extended Termination Associated Sequence (ETAS) previously reported in Scomberoides commersonianus, a member of the Carangidae25, could not be aligned to the corresponding segment in the control region of either species.

Sequence and structure of the mitochondrial DNA control region of carangids (a) Features of the control region. CSB-F,-D,-E: central conserved sequence blocks; CSB-1,-2,-3: conserved sequence blocks. Palindromic sequence motifs 'TACTA' and 'ATGTA' are framed. Grey colored bar represents the characteristic 3' terminal sequence. (b) The secondary structure identified in CSB-F, CSB-D, and CSB -E. (c) Secondary structure identified in CSB-1, CSB-2, and CSB-3. The secondary structures of conserved sequence motifs were predicted by the online Mfold web server (http://www.unafold.org/).

No tandem repeat sequences were detected in the control region of Carangidae, but the T homopolymer of 5–12 nucleotides between CSB-D and CSB-1 was found in all taxa. Along with these discontinuous multiple interval repeats of ATATTA and TATAAT were also observed in the control region of Carangidae.

All species except D. maruadsi displayed substantial differences from the key sequences of CSB- E25 and all were substitutions ranging from 1 to 9 nucleotides. Furthermore, M. cordyla, P. dentex, and Caranx spp. lacked a 'GTGGG'- box which is a typical feature of CSB- E in teleosts69. The CSB- D was highly conserved among carangids and exhibited high sequence similarity between species (Table 4). Although the functions of the CSBs remain unclear, CSB-D is highly conserved in fish families and is involved in regulation of H-strand replication and initiation of D-loop structure70 and could play a potential role in mitochondrial metabolism66. Conserved sequence blocks (CSB-1,-2, and -3) exhibit a higher level of divergence in carangids with interspecies substitutions, insertions, and deletions (Table 4). Except for P. dentex, S. nigrofasciata, S. leptolepis and Seriola spp. other species showed a characteristic sequence at the 3' end (Table 4). These variations imply rapid evolution of the primary structure in the Carangidae control region, which can provide information for understanding their structural and functional relationship. Furthermore, these conserved regions are involved in the formation of secondary structures in the control region (Fig. 2) that serve as the target sites for proteins or enzymes69. These conserved sequence motifs formed similar secondary structures in Carangidae although their primary sequences are not conserved. Therefore, the data reinforce that although there is sequence divergence in the conserved sequence motif, their structural elements and locations appeared to be conserved in Carangidae and some selective constraints on these regions acted to maintain their structure and function.

Carangidae mitogenome sequence comparison

We compared the complete mitochondrial genome of D. russelli with other available mitogenomes of the Carangidae family. The DNA coding sequences showed high interspecies identity (Supplementary Figs. S8, S9). The control region contributed to a larger percentage difference between the nucleotide sequences. It has been found that ND1, COI, COII and COIII are highly conserved among the DNA coding sequences. In addition, ATP8 was the least conservative of all species, in good agreement with the results obtained from analysis of Ka/Ks and overall mean p genetic distance. With the exception of ND6 and Cyt-b, other PCGs expressed orthologous group (COG) clusters. A total of 12 COGs of proteins were detected from11 PCGs. ND5 was determined to have 2 COGs, pCOG, and cCOG, and the remaining 10 PCGs each expressed a single COG each (cCOG). COGs are a group of proteins inferred to be orthologous i.e. they are direct evolutionary counterparts71. Lineage-specific duplications (orthologous relationships) exist mainly between gene (protein) families rather than between individual proteins72. The identification of COGs associated with specific PCGs could indicate the presence of a specific protein in a specific species, and it is crucial to determine the functional relevance of these proteins in that specific species73. The results indicated that the COGs present in carangids are involved in inorganic ion transport and metabolism (pCOG) and energy production and conservation (cCOG)72. The ND5 gene has been found to perform these two functions, while energy metabolism is the sole function of the remaining 10 PCGs.

Phylogenetic analysis

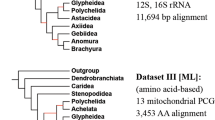

The phylogenetic position of D. russelli is shown in Fig. 3 relative to 36 species of carangids based on 1380 bp sequences. Analogous topologies were obtained for both maximum likelihood analysis (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) with almost 100% bootstrap support and strong posterior probability values, respectively (Fig. 3). The result implied that 37 species formed 3 lineages corresponding to the subfamilies Caranginae, Naucratinae, and Trachinotinae. The reconstructed phylogenetic tree places D. russelli in the same branch with other Decapterus spp. and forms a sister group to the genus Trachurus and the findings support the previous classification of carangids44,74. The phylogenetic tree recovered the three carangid subfamilies as monophyletic and it also supported the groupings (Trachinotinae + (Naucratinae + Caranginae)). This result confirmed the phylogenetic relationship of carangids described by previous findings based on morphological synapomorphic characters4,31 and partial sequences of mitochondrial genes32,75. Within the Naucratinae, the monotypic E. bipinnulata branched individually early from Seriolina and Seriola spp. After diverging from Seriolina, all Seriola species formed a monophyletic clade. Furthermore, both phylogenetic trees indicated two well-separated lineages in Caranginae. The first lineage included the genus Selar, Trachurus, and Decapterus. This lineage also encompassed the species C. equula on the same branch with P. dentex in contrast to other Carangoides Spp. which were grouped into a different branch (Fig. 3). This result confirms the findings of previous studies44,76 and thus provides compelling evidence for the assignment of C. equula to its previously described genus, Kaiwarinus. The second lineage was the most taxonomically diverse group of the family Carangidae delineated in the present study as it consisted of 10 genera divided into two larger groups. The first lineage comprised the genera: Caranx + Megalaspis + Gnathandon as well as Atule + Alepes. The latter also included the monotypic S. leptolepis which individually branched off from this lineage early. The second lineage included Uraspis + Parastromateus and Alectis + Carangoides. In addition, a paraphyletic relationship between Caranx + M. cordyla, Alepes + A. mate, and Uraspis + P. niger was also observed.

Phylogenetic tree inferred from the nucleotide sequences of 13 concatenated PCGs of 37 species of Carangidae. Bayesian posterior probabilities (left) and bootstrap support values (right) are superimposed with each node. The phylogenetic tree was generated by using MrBayes 3.2.7a93.

Divergence time estimation

The RelTime ML analysis revealed that the differentiation of D. russelli could be dated back to about 4.69 Mya in the early Pliocene. The family Carangidae had diverged from other lineages when the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event occurred and it was estimated to be around 79 Mya towards the end of the cretaceous (Supplementary Fig. S10). It was observed that the separation of the two groups, Trachinotinae and (Caranginae + Naucratinae) occurred at 74 Mya at the end of the Cretaceous. Further, the split between the subfamilies Caranginae and Naucratinae occurred at 62.20 Mya (Early Paleocene). Although the diversification of most species after the Cretaceous mass extinction occurred in the Paleogene75, several more recent Neogene radiations can also be observed (Fig. 4).The most recent split was observed at 0.34 Mya between the two Uraspis species. Our analyzes of the diversification of the genus Trachurus (18.40 Mya, early Miocene) were consistent with previous studies based on the data of morphological characters and ecological aspects77 and cyt b gene sequence analysis78. The split between Seriola + Seriolina and Elgatis occurred during the early Paleocene, consistent with Swart et al.40 but much younger than Le et al.44. The radiation of Seriola appears to be 20.87 Mya which is in direct agreement with Le et al.44, but slightly predates the estimates by Santini and Carnevale38.

Timetree chronogram of 37 species of Carangidae for the 13 PCGs inferred from Bayesian topology. Divergence times were estimated using 32 calibrations. The red text indicates the species sequenced in this study. The Timetree was generated by using MEGA X96.

Conclusion

The present investigation focused on the characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the Indian Scad, D. russelli, and a comprehensive comparative analysis of Carangidae with special emphasis on the structure and variability of tRNA and control region. The carangid tRNA was structurally different in both the stem and loop, with the exception of tRNA-Trp, and tRNA-Leu (TAG). These structural features resulted in mismatched or wobble base pairs in tRNAs. The high rate of Watson–Crick and Wobble base pairing in the stem regions of tRNA suggested their role in stem structure maintenance. The classical cloverleaf secondary structure was retained in all tRNAs except tRNA-Ser (GCT). The presence of an mTERF binding site and a very high evolutionary conservation of its sequence suggest the functional significance of these sites. The high rate of sequence divergence in the flanking regions of conserved sequence motifs indicated the absence of typical mitochondrial control region coding constraints. The presence of evolutionarily conserved secondary structures of the conserved sequence motifs despite sequence divergence revealed the effect of selective constraints on their maintenance. The length variations in protein-coding, tRNA, and rRNA genes among Carangidae were negligible.

The phylogeny inferred from 13 gene concatenated data set resolved the monophyletic lineage of each subfamily and robustly supported the grouping (Trachinotinae + (Caranginae + Naucrautinae)) with the caveat that the subfamily Scomberoidinae could not be included as the mitogenome sequences were not available. Further, the speciation of the genus Decapterus occurred before the separation of Tethys Sea and D. russelli diverged before the mid-Pliocene warm period. Future studies involving the mitogenomic data of Scomberoidinae are required for a better understanding of the phylogenetic and evolutionary relationship between major groups within the Carangidae. Mitogenomic phylogeny is also influenced by the habitat characteristics of each group, as habitat-specific selection and adaptation in mitochondrial coding genes has recently been reported79. The subfamilies Trachinotinae, Naucratinae, and Caranginae consist of species with differential habitat preferences (pelagic, benthopelagic, and reef-associated) and schooling behavior. The mutational patterns in the protein-coding regions of these fish need to be further analyzed for adaptive variation and selection and correlated with habitat characteristics to understand the forces of selection, if any.

Materials and methods

Sampling

The wild specimen of D. russelli was collected from Kochi, Kerala (9°56′19"N 76°15′45" E) from trawl and purse seines. The species was confirmed based on morphological characters. Tissue samples were preserved in 95% ethanol for DNA extraction and further analysis. The fish sample used in this study was handled according to the guidelines for the care and use of fish in research by De Tolla et al.80. The protocols were approved by the ethical committee of the ICAR- Central Marine Research Institute, Kochi. These methods are also reported following ARRIVE guidelines (http://arriveguidelines.org).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described81. The extracted DNA was then eluted in T.E buffer (1X) and stored at − 20 °C for later use as a PCR template. The quality and quantity (concentration) of the isolated total DNA was checked by gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop One Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), respectively. The complete mitochondrial genome of D. russelli was determined by combining the sequences of contiguous and overlapping fragments amplified by PCR using both universal as well as custom-designed primers. Initial amplifications were performed using mitochondrial universal primer sequences (FishF1 + FishR1, 16SaRL + 16SbRH, 12S1 + 12S2, Dloop-Thr-F + Dloop-Phe-R, ATP 8.2 L8331 + CO3.2 H9236)82,83,84,85,86. The sequenced products of this reaction then served as a template for subsequent amplification. Fifteen sets of new primer pairs were designed based on the aligned complete mitogenome sequences of 36 species of carangids using Primer 3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/)87. The above primers were screened for potential secondary targets using Primer Blast (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/)88. PCR amplifications were performed in a Biorad T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). The reaction mixture included 15.6 µl sterile deionized water, 2 µl buffer (10X), 0.4 µl dNTP mix (10 mM each), 0.4 µl of each oligonucleotide (10 µM), 1 µl of template DNA (50 ng/µl) and 0.2 µl (1 unit) of Taq DNA polymerase with a total reaction volume of 20 µl. For confirmation, PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel (1X TBE) and visualized using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, USA). The products were then sequenced completely in both directions using sanger sequencing.

Sequence analysis

Target sequences were assembled with the software MEGA X89. The identity of the D. russelli mitogenome was verified with other carangid mitogenomes (Supplementary Table S2) by BLAST search. These mitogenome sequences served as the reference for assembly and manual annotations. The organization and the order of the genes were initially determined using the MitoFish database90 and later verified manually by comparison with the reference sequences. The 13 PCGs and their codon usage were summarized with MEGA X89. The rate of Ka/Ks substitutions in the mitogenome of Carangidae was calculated by DnaSP 6.12.0391. tRNA genes were first annotated by using tRNA scan SE92 with default parameters coupled with ARWEN software57. The secondary structure of conserved sequence motifs of the control region was inferred using Mfold web server93. The complete mitogenome map of the species was graphically visualized by OrganellarGenomeDRAW94. The 37 mitogenomes of Carangidae were compared by using CG view comparison tool (CCT)95 with D. russelli as the reference sequence. Genes were assigned by Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) using the CG view comparison tool (CCT) and BLAST was used to align other genomes to that of D. russelli.

Phylogenetic analysis

All available mitogenome sequences of other carangid species were retrieved from GenBank to find out the relative position of D. russelli among carangids and to delineate its phylogenetic relationship. L. crocea (GenBank accession number NC011710) was taken as an outgroup. The 13 PCGs were aligned using Clustal W and translated into amino acid sequences in MEGA X57. For the subsequent phylogenetic analysis, multiple alignments were generated for the 13 concatenated protein-coding sequences of D. russelli and 36 other Carangidae species. The phylogenetic relationship was inferred by constructing a tree based on Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods. The best model, GTR + G + I, was selected using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed using MrBayes96 with the Markov Chain Monte Karlo Method (MCMC). MCMC chains were run for 10 million generations and obtained a standard deviation of split frequency less than 0.01. The ML phylogenetic tree was inferred using RaxML97 and a consensus tree was obtained with 1000 bootstrap replicates using default parameters. The final phylogenetic tree was displayed, annotated, and embellished in FigTree software (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/)98.

Divergence time estimation

Molecular dating of 37 Carangidae species was performed with the RelTimeML method in MEGA X99 using GTR + G + I modeling. The phylogenetic tree inferred from Bayesian analysis was imported to MEGA X to estimate divergence times. The time tree web resource (http://www.timetree.org/)100 was used to infer calibration boundaries for a pair of taxa (minimum and maximum) and the same database was used to establish the time tree of 27 genera of carangids.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study is included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files).

References

Lin, P. L. & Shao, K. T. A review of the carangid fishes (Family Carangidae) from Taiwan with descriptions of four new records. Zool. Stud. 38, 33–68 (1999).

Honebrink, R. A review of the biology of the family Carangidae, with emphasis on species found in Hawaiian waters. Division of Aquatic Resources Technical report 20–01, Department of Land and Natural Resources: Honolulu, HI, USA. (2000).

Laroche, W. A., Smith-Vaniz, W. F. & Richardson, S. L. Carangidae: Development in Ontogeny and Systematics of Fishes (ed. Moser, H.G. et al.) 510–522 (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Special Publications, 1984).

Gushiken, S. Phylogenetic relationships of the perciform genera of the family Carangidae. Ichthyol. Res. 34, 443–461 (1988).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. http://www.fishbase.org, (2021).

Rohfritsch, A. & Borsa, P. Genetic structure of Indian scad mackerel Decapterus russelli: Pleistocene vicariance and secondary contact in the Central Indo-West Pacific Seas. Heredity 95, 315–326 (2005).

Balasubramanian, N. K. & Natarajan, P. Studies on the biology of the scads, Decapterus russelli and Decapterus macrosoma at Vizhinjam, southwest coast of India. Indian. J. Fish. 47, 291–300 (2000).

Murty, V. S. Observations on some aspects of biology and population dynamics of the scad Decapterus russelli (Ruppell) (Carangidae) in the trawling grounds off Kakinada. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. India. 33, 396–408 (1991).

Raje, S. G. On some aspects of biology of the mackerel scad Decapterus russelli (Ruppell). Indian. J. Fish. 44, 97–99 (1997).

Jaiswar, A. K., George, J. P., Gulati, D. K. & Swamy, R. P. A study on length-weight relationship, food and feeding habits of Indian scad, Decapterus russelli (Ruppel, 1830) along the northwest coast of India. J. Indian Fish. Assoc. 23, 1–6 (1993).

Poojary, N., Tiwari, L. R. & Jaiswar, A. K. Food and feeding habits of the Indian scad, Decapterus russelli (Ruppell, 1830) from Mumbai waters, north-west coast of India. Indian. J. Fish. 57, 93–99 (2010).

Sunil, V. & Suryanarayanan, H. The reproductive biology of Ambassis gymnocephalus and Decapterus russelli in the Neendakara Zone, Kerala. J. Anim. Morphol. Physiol. 41, 119–123 (1994).

Moiseyeva, Y. B. & Zhuk, N. N. Oogenesis in some species of carangids in the west Indian Ocean. J Icthyol. 35, 137–149 (1995).

Manojkumar, P. P. Maturation and spawning of Decapterus russelli (Ruppell, 1830) along the Malabar Coast. Indian. J. Fish. 52, 171–178 (2005).

Kalhoro, M. T. et al. Stock assessment of Indian Scad, Decapterus russelli in Pakistani marine waters and its impact on the national economy. Fish Aqua. J. 8, 1J-1J (2017).

Reuben, S. et al. Fishery, biology and stock assessment of carangid resources from the Indian seas. Indian. J. Fish. 39, 195–234 (1992).

Manojkumar, P. P. Stock assessment of Indian scad, Decapterus russelli (Ruppell, 1830) off Malabar. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. India. 49, 79–80 (2007).

Sen, S. et al. Stock structure analysis of Decapterus russelli (Ruppell, 1830) from east and west coast of India using truss network analysis. Fish. Res. 112, 38–43 (2011).

Boore, J. L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 27, 1767–1780 (1999).

Jacobsen, M. W., Da Fonseca, R. R., Bernatchez, L. & Hansen, M. M. Comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes suggests that relaxed purifying selection is driving high nonsynonymous evolutionary rate of the NADH2 gene in whitefish (Coregonus ssp.). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 95, 161–170 (2016).

Brown, W. M., Prager, E. M., Wang, A. & Wilson, A. C. Mitochondrial DNA sequences of primates: tempo and mode of evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 18, 225–239 (1982).

Saccone, C., Pesole, G. & Sbisá, E. The main regulatory region of mammalian mitochondrial DNA: structure-function model and evolutionary pattern. J. Mol. Evol. 33, 83–91 (1991).

Foran, D. R., Hixson, J. E. & Brown, W. M. Comparisons of ape and human sequences that regulate mitochondrial DNA transcription and D-loop DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 5841–5861 (1988).

Sebastian, W., Sukumaran, S. & Gopalakrishnan, A. The signals of selective constraints on the mitochondrial non-coding control region: insights from comparative mitogenomics of Clupeoid fishes. Genetica 149, 1–11 (2021).

Zhu, S. H., Zheng, W. J., Zou, J. X., Yang, Y. C. & Shen, X. Q. Mitochondrial DNA control region structure and molecular phylogenetic relationship of Carangidae. Zool Res. 28, 606–614 (2007).

Suzuki, K. Anatomical and taxonomical studies on the carangid fishes of Japan. Rep. Fac. Fish. Prefect. Un. Mie. 4, 43–232 (1962).

Smith-Vaniz, W. F. & Staiger, J. C. Comparative revision of Scomberoides, Oligoplites, Parona, and Hypacanthus with comments on the phylogenetic position of Campogramma (Pisces: Carangidae). Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. 39, 185–256 (1973).

Smith-Vaniz, W. F. Carangidae in Sea Fishes (ed. Smith, M. M & Heemstra, P. C.) 638–660 (Springer, 1986).

Springer, V. G. & Smith-Vaniz, W. F. Supraneural and pterygiophore insertion patterns in carangid fishes, with description of a new Eocene carangid tribe,† Paratrachinotini, and a survey of anterior anal-fin pterygiophore insertion patterns in Acanthomorpha. Bul. Biol. Soc. Wash. 16, 1–73 (2008).

Hilton, E. J., Johnson, G. D. & Smith-Vaniz, W. F. Osteology and Systematics of Parastromateus niger (Perciformes: Carangidae), with Comments on the Carangid Dorsal Gill-Arch Skeleton. Copeia 2, 312–333 (2010).

Smith-Vaniz, W. F. Carangidae: relationships in Ontogeny and Systematics of Fishes (ed. Moser, H.G. et al.) 522–530 (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Special Publications, 1984).

Reed, D. L., Carpenter, K. E. & Martin, J. D. Molecular systematics of the Jacks (Perciformes: Carangidae) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b sequences using parsimony, likelihood, and Bayesian approaches. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 23, 513–524 (2002).

Reed, D. L., deGravelle, M. J. & Carpenter, K. E. Molecular systematics of Selene (Perciformes: Carangidae) based on cytochrome b sequences. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 21, 468–475 (2001).

Cárdenas, L. et al. Origin, diversification, and historical biogeography of the genus Trachurus 385 (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 35, 496–507 (2005).

Betancur-R, R., Li, C., Munroe, T. A., Ballesteros, J. A. & Ortí, G. Addressing gene tree discordance and non-stationarity to resolve a multi-locus phylogeny of the flatfishes (Teleostei: Pleuronectiformes). Syst. Biol. 62, 763–785 (2013).

Near, T. J. et al. Phylogeny and tempo of diversification in the superradiation of spiny-rayed fishes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 12738–12743 (2013).

Rabosky, D. L. et al. Rates of speciation and morphological evolution are correlated across the largest vertebrate radiation. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–8 (2013).

Santini, F. & Carnevale, G. First multilocus and densely sampled timetree of trevallies, pompanos and allies (Carangoidei, Percomorpha) suggests a Cretaceous origin and Eocene radiation of a major clade of piscivores. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 33–39 (2015).

Britz, R. & Johnson, G. D. Ontogeny and homology of the skeletal elements that form the sucking disc of remoras (Teleostei, Echeneoidei, Echeneidae). J. Morphol. 273, 1353–1366 (2012).

Swart, B. L., von der Heyden, S., Bester-van der Merwe, A. & Roodt-Wilding, R. Molecular systematics and biogeography of the circumglobally distributed genus Seriola (Pisces: Carangidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 93, 274–280 (2015).

Bannikov, A. F. On the taxonomy, composition and origin of the Family Carangidae. J. Ichthyol. 27, 1–8 (1987).

Kijima, A., Taniguchi, N. & Ochiai, A. Genetic divergence and relationship among fifteen species of genera Trachurus, Decapterus Selar and Selaroides. Jpn. J. Ichthyol. 35, 167–175 (1988).

Nichols, J. T. Notes on carangin fishes. 6, East Indian mackerel scads (Decapterus) described and differentiated. Am. Mus. Novit. 1196, 1–8 (1942).

Li, Z. et al. Complete mitogenomes of three carangidae (perciformes) fishes: genome description and phylogenetic considerations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4685 (2020).

Li, M. et al. Whole mitogenome of the Japanese scad Decapterus maruadsi (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27, 306–307 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Characterization of the mitochondrial genome of the Shortfin scad Decapterus macrosoma (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27, 82–83 (2016).

Zou, K., Chen, Z., Zhang, P. & Li, M. Mitochondrial genome of the Mackerel scad Decapterus macarellus (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27, 2151–2152 (2016).

Norfatimah, M. Y., Teh, L. K., Salleh, M. Z., Isa, M. M. & SitiAzizah, M. N. Complete mitochondrial genome of Malaysian Mahseer (Tor tambroides). Gene 548, 263–269 (2014).

Xie, X. Y., Huang, G. F., Li, Y. T., Zhang, Y. T. & Chen, S. X. Complete mitochondrial genome of Acrossocheilus parallens (Cypriniformes, Barbinae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27, 3339–3340 (2016).

Nardi, F., Carapelli, A., Fanciulli, P. P., Dallai, R. & Frati, F. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the basal hexapod Tetrodontophora bielanensis: evidence for heteroplasmy and tRNA translocations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 1293–1304 (2001).

Wang, X. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of javeline goby (Synechogobius hasta). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27, 4586–4587 (2016).

Hurst, L. D. The Ka/Ks ratio: diagnosing the form of sequence evolution. Trends Genet. 18, 486–486 (2002).

Shi, X., Tian, P., Lin, R., Huang, D. & Wang, J. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the globose head whiptail Cetonurus globiceps (Gadiformes: Macrouridae) and its phylogenetic analysis. PLoS ONE 11, e0153666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153666 (2016).

Yang, H. et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome sequences of three croakers (perciformes, sciaenidae) and novel insights into the phylogenetics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1741 (2018).

Zhuang, X., Qu, M., Zhang, X. & Ding, S. A comprehensive description and evolutionary analysis of 22 grouper (Perciformes, Epinephelidae) mitochondrial genomes with emphasis on two novel genome organizations. PLoS ONE 8, e73561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073561 (2013).

Stepien, C. A. & Kocher, T. D. Molecules and morphology in studies of fish evolution in Molecular systematics of fishes (ed. Kocher, T. D. & Stepien, C. A.) 1–11 (Academic press, 1997).

Laslett, D. & Canbäck, B. ARWEN: a program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 24, 172–175 (2008).

Janke, A. & Pääbo, S. Editing of a tRNA anticodon in marsupial mitochondria changes its codon recognition. Nucleic acids Res. 21, 1523–1525 (1993).

Zhu, K. C. et al. Sequencing and characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Japanese Swellshark (Cephalloscyllium umbratile). Sci. Rep. 7, 1–14 (2017).

Zardoya, R. & Meyer, A. The complete DNA sequence of the mitochondrial genome of a “living fossil”, the coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae). Genetics 146, 995–1010 (1997).

Xiao, X., Yang, S., Lin, D., Wang, Y. & Hua, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome and phylogenetic analysis of Chinese Jianchang horse (Equus caballus). Cloning Transgenes. 5, 2 (2016).

Jang, Y. S. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the dark-banded rockfish Sebastes inermis (Scorpaenidae, Scorpaeniformes). Mitochondrial DNA 26, 895–896 (2015).

Li, M., Li, Y. & Chen, Z. Mitochondrial genome of the Torpedo scad Megalaspis cordyla (Perciformes: Carangidae): genome characterization and phylogenetic consideration. Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 27, 1856–1857 (2016).

Sprinzl, M., Horn, C., Brown, M., Ioudovitch, A. & Steinberg, S. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucl. Acids Res. 26, 148–153 (1998).

Varani, G. & McClain, W. H. The G· U wobble base pair. A fundamental building block of RNA structure crucial to RNA function in diverse biological systems. EMBO Rep. 1, 18–23 (2000).

Satoh, T. P., Miya, M., Mabuchi, K. & Nishida, M. Structure and variation of the mitochondrial genome of fishes. BMC Genom. 17, 1–20 (2016).

Christianson, T. W. & Clayton, D. A. A tridecamer DNA sequence supports human mitochondrial RNA 3’-end formation in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 4502–4509 (1988).

Broughton, R. E., Milam, J. E. & Roe, B. A. The complete sequence of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) mitochondrial genome and evolutionary patterns in vertebrate mitochondrial DNA. Genome Res. 11, 1958–1967 (2001).

Lee, W. J., Conroy, J., Howell, W. H. & Kocher, T. D. Structure and evolution of teleost mitochondrial control regions. J. Mol. Evol. 41, 54–66 (1995).

Clayton, D. A. Replication of animal mitochondrial DNA. Cell 28, 693–705 (1982).

Koonin, E.V. The Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) Database: phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes in The NCBI handbook (ed. McEntyre, J & Ostell, J) 21–27 (The National Library of Medicine Press, 2010).

Natale, D. A. et al. Towards understanding the first genome sequence of a crenarchaeon by genome annotation using clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COGs). Genome Biol. 1, 1–19 (2000).

Remm, M., Storm, C. E. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Automatic clustering of orthologs and in-paralogs from pairwise species comparisons. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 1041–1052 (2001).

Ma, H. et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome and phylogenetic relationship of Caranx tille (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part A 27, 4704–4705 (2015).

Zinsmeister, W. J. Discovery of fish mortality horizon at the KT boundary on Seymour Island: re-evaluation of events at the end of the Cretaceous. J. Paleontol. 72, 556–571 (1998).

Li, B., Wang, H., Yang, L., Liu, S. & Zhuang, Z. Complete mitochondrial genome of pseudocaranx dentex (carangidae, perciformes) provides insight into phylogenetic and evolutionary relationship among carangidae family. Genes 12, 1234 (2021).

Shaboneyev, I. Y. Systematics, morpho-ecological characteristics and origin of Carangids of the genus Trachurus. J. Ichthyol. 20, 15–24 (1981).

Cárdenas, L. et al. Origin, diversification, and historical biogeography of the genus Trachurus (Perciformes: Carangidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 35, 496–507 (2005).

Sebastian, W. et al. Signals of selection in the mitogenome provide insights into adaptation mechanisms in heterogeneous habitats in a widely distributed pelagic fish. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–14 (2020).

DeTolla, L. J. et al. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Fish in Research. ILAR J. 37, 159–173 (1995).

Sambrook, J. D. & Russell, W. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual 2028 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2001).

Ward, R. D., Zemlak, T. S., Innes, B. H., Last, P. R. & Hebert, P. D. DNA barcoding Australia’s fish species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360, 1847–1857 (2005).

Palumbi, S. R. Nucleic acids II: the polymerase chain reaction, in Molecular systematics (ed. Hillis, D.M., Moritz, C. & Mable, B.K.) 205–247 (Sinauer & Associates Inc, 1996).

Infante, C. et al. PCR-based methodology for the authentication of the Atlantic mackerel Scomber scombrus in commercial canned products. Food. Res. Int. 39, 1023–1028 (2006).

Cheng, Y. Z. et al. Universal primers for amplification of the complete mitochondrial control region in marine fish species. Mol. Biol. 46, 727–730 (2012).

Sivasundar, A., Bermingham, E. & Ortí, G. Population structure and biogeography of migratory freshwater fishes (Prochilodus: Characiformes) in major South American rivers. Mol. Ecol. 10, 407–417 (2001).

Rozen, S. & Skaletsky, H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers in Bioinformatics methods and protocols 365–386 (Humana Press, 2000).

Ye, J. et al. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 13, 1–11 (2012).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Iwasaki, W. et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: a mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2531–2540 (2013).

Rozas, J. et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Chan, P. P., Lin, B. Y., Mak, A. J. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/614032v2 (2021).

Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucl. Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 (2013).

Greiner, S., Lehwark, P. & Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucl. Acids Res. 47, W59–W64 (2019).

Grant, J. R., Arantes, A. S. & Stothard, P. Comparing thousands of circular genomes using the CGView Comparison Tool. BMC genom. 13, 1–8 (2012).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Rambaut, A. FigTree v1.4.3. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/, (2016).

Mello, B. Estimating timetrees with MEGA and the TimeTree resource. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 2334–2342 (2018).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Suleski, M. & Hedges, S. B. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812–1819 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. P. Vijayagopal, Head in charge, Marine Biotechnology Division (MBTD) and Director, ICAR- Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi for providing the necessary facilities for conducting the research. The first author is grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) for the financial assistance in the form of a research fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J. performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data and prepared the main manuscript text. S.S. conceptualized and coordinated the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L.P.M. and S.M. participated in the data analysis. N.R. and N.K. prepared Fig. 1. A.G. supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jose, A., Sukumaran, S., Mukundan, L.P. et al. Comparative mitogenomics and phylogenetics of the family Carangidae with special emphasis on the mitogenome of the Indian Scad Decapterus russelli. Sci Rep 12, 5642 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09636-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09636-5

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.