Chesney Hawkes, the one and only, is sitting on my sofa with a mug of lemon and ginger tea and recalling some encounters with fans. “I was told that, this one guy, The One and Only was his favourite song, and whenever it would come on in the pub, his friends would pick him up and he’d be like …” He makes disco fingers at the ceiling. “Then he sadly passed away, but they played it at the funeral, and when it came on, that’s when they raised the coffin.”

We are silent for a moment, picturing the scene.

Gosh, I say. “I know, right? Real lump-in-the throat time. That’s when I realised that, this song, I don’t have ownership of it. It went out there and made an emotional connection with people and that has nothing to do with me,” he says, then sips his tea.

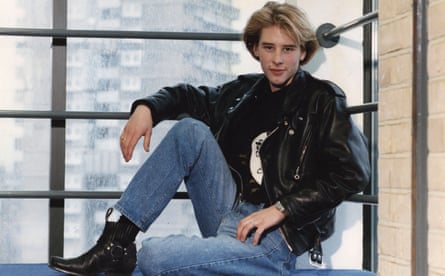

Before Hawkes arrives, I worry that I will struggle to see him as the 50-year-old father of three he is, rather than the teenage heart-throb who sang one of the catchiest No 1 singles of all time. Fortunately, he makes it easy for me, because he turns up with his son Casey, who, at 20, is older than his father was in his pop heyday. They have an appointment to renew Casey’s passport later this afternoon – and you can’t really swoon over a man on his way to the Passport Office, even if he once was the biggest pop star in the world.

We are meeting at mine because it is in between the passport place and where the Hawkeses are staying on this trip. Hawkes’ wife, Kristina, is American and the family live in Los Angeles, but the UK is where Hawkes was born and where he works. “A typical day here might be: get up, do a couple interviews; there might be a rehearsal with the band, possibly a gig. I just did Butlin’s up in Skegness,” he says, with that sweet smile that hasn’t dimmed in the past three decades. He is so sunny, as open as a flower, that it is hard to believe he has ever heard a harsh word in his life, let alone been an object of derision for years, his name a byword for shallow pop and short‑lived success.

Many one-hit wonders coast in on brief novelty – Baby Got Back by Sir Mix-a-Lot, say, or Mr Blobby – so the ones that endure, that people still dance to in their kitchens decades later, are an elite, eclectic bunch. There is the Knack’s My Sharona, of course, plus 99 Red Balloons by Nena, Tiffany’s I Think We’re Alone Now and Steal My Sunshine by Len. And then there is Hawkes’ The One and Only, still sounding as sweetly endearing as it did in 1991. During lockdown, Hawkes and his children cheered up the country by singing it on This Morning. For Hawkes, there is a vindication of sorts in this, not to mention some employment, and it has been a long time coming.

I was 12 when The One and Only was released, only seven years younger than Hawkes. My friends and I read every interview with “Chezza” in Smash Hits, so we knew all about him: that his dad was in some 60s band, which didn’t interest us at all, and that his younger brother, Jodie, was his drummer, which interested us a lot. We knew that he – alongside some old guy called Roger Daltrey – was the star of the movie Buddy’s Song, in which he sang The One and Only, and some of us even went to see it. We followed the exciting rumours about the mole above his right lip – or was it his left? – and whether it was fake. Most of all, we sang the song, belting it out in the schoolyard every breaktime.

I noticed that his follow-up singles (I’m a Man Not a Boy and Secrets of the Heart – and no, I didn’t need to Google the titles, thanks very much) didn’t sell as well, after which he disappeared, but I wasn’t concerned. After all, he had been No 1 in the UK for five weeks. Surely he was just living off his riches somewhere.

What happens to one-hit wonders when the hit has gone? Their names are too recognisable for them to get a normal job, but they can’t live without one. Hawkes was in the extra-unfortunate position of not having written The One and Only – Nik Kershaw did – meaning that he didn’t make as much from the song as I had assumed. The money he did get he spent exactly how a nice but naive 19-year-old would: “I bought cars for everyone in my family; I bought the stupid little red sports car. And my parents were not so good with money, either, so they didn’t have advice for me,” he says.

Nor did his record company offer any guidance. Two years after The One and Only, with his subsequent singles – which he wrote – and album failing to live up to expectations, it dropped him.

“It was like losing a family: the record company girls who feel like sisters, because they travel around with you a lot; the people involved in the promotions. I was 18 when I met them all, so I was really taken aback when I suddenly couldn’t get any of these people on the phone. It was a big learning curve for me when I realised: ‘Oh, OK, none of that was real and I’m a washed-up pop star at 23,’” he says. With friends, he formed bands “and gave them names like Ebb and Fly. We thought we were Radiohead, basically.” In the space of three years, he went from palling around with Take That to flat-sharing in Barnes, west London.

In the 90s, the press took it for granted that Hawkes was just another boring pretty boy, but his background is fascinating. His father, Len “Chip” Hawkes, was the singer in the beat group the Tremeloes, so Hawkes and his siblings grew up in a house often filled with 60s rock’n’rollers. Gerry Marsden from Gerry and the Pacemakers, Herman’s Hermits, Marmalade, the Searchers and Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich were regular guests.

“My parents were like rock’n’roll hippies, with my mum always in really short skirts; my dad still has long hair. They would throw parties all the time and when we’d get up for school, we’d have to step over one or two musicians to get to our cornflakes,” he says.

On top of that, his parents were – improbably – born-again Baptists. “They pulled us kids into it,” he says. They sent them to Christian camps, where the leaders would say angels had visited the night before. Some of the kids talked in tongues. “It was the worst,” says Hawkes.

Somehow, despite this double whammy of rock excess and religious nuttiness, Hawkes remained a gentle, level-headed kid who just wanted to make music. But that dream went sour when he was barely in his 20s. “Piers Morgan and [the entertainment journalist] Rick Sky – you know those guys? They picked on me a lot. It was a daily thing. At the time I was like: ‘I’m fine, I’m fine,’ but I was still really young then and you realise later that stuff went in,” he says. Hawkes tried to block out the noise by sticking with his brother and the friends he had had since childhood. But how did he not lose the plot?

“I think it was Jodie, to be honest with you. He has been a huge, huge crutch for me. He went through it all with me and he’s a very stable guy, so he really helped me. And my dad, bless him, as scatty and crazy as he can be. There’s a lot of love in my family,” he says.

Another stabilising force entered his life in 1995, when he happened to go to a pub in Barnes, to see a mate play a gig, and two American models walked in. “It was crazy that they were there and not, say, in the West End, but I walked up to one and asked if I could buy her a drink and she said: ‘I’ll have a pint of lager, please.’ I was like: ‘Oh my God! Will you marry me?’” She did – a little later – and he and Kristina have been together ever since.

“She had no idea who I was when we met and she keeps me on a level emotionally. Also financially, because, when we met, I was very much in a hole. Then she came along. Her father was a banker and she is very, very good with money. So she was like: ‘OK, let’s restructure you here.’”

The family moved to LA 10 years ago, mainly for adventure, but also with the idea that Hawkes could write music for other artists. “But the business is tough and it was the wrong timing for me. Nowadays, it’s no good just to get a song on an album, because there’s no money in songs. You need a single, unless you’re with Adele or Ed Sheeran,” he says.

Instead, Hawkes has found an unexpected career on what he describes as the “heritage circuit”. The other week, he did a gig in Manchester alongside the Vengaboys and “that band that sang Cotton Eye Joe” (Rednex). Other bands and singers he shares a bill with frequently include Katrina and the Waves (“always look forward to seeing them”), Jason Donovan (“a mate”), Tiffany (“so lovely”) and Carol Decker from T’Pau (“love Carol Decker.”) I tell him I had a taste of the heritage circuit when I took my kids to Camp Bestival a few years back and Rick Astley was headlining.

“Rick’s had an amazing career, with the Rickroll thing,” he says with enthusiasm, referring to the online prank whereby clicking an unrelated link takes the browser to the video for Astley’s 1987 hit Never Gonna Give You Up.

It is slightly more than 30 years since The One and Only. To mark the occasion, Hawkes is putting out a five-CD box set, The Complete Picture, featuring all the songs he has written over the years. He is hoping that it will wake people up to the fact that he is more than just that song.

Did he ever consider leaving music behind? “I can’t – it’s like breathing to me. I can’t even walk past a guitar without picking it up. I’m not bitter about what happened, but I do sometimes have a pang and think: what if my career had carried on a little longer? What if I’d released different singles? You overthink things, don’t you? But, in general, I’m very happy with where I am. I’m very much in love with my wife; my kids are amazing. It’s a steady, day-to-day kind of happiness.”

Things have not been easy for the Hawkes family recently. His father was diagnosed with cancer a decade ago. Eight years ago, his father and another of the Tremeloes, Richard Westwood, were accused of indecently assaulting a minor in 1968. After two years, a judge ordered the pair be found not guilty.

Hawkes thought he had already experienced all the downsides to fame, but this was a new low. “It was a terrible time, with people turning up to the house. But my dad is made of stronger stuff than most,” he says. When his dad has been feeling unwell due to the cancer, Hawkes has subbed for him at Tremeloes gigs – a kind of double-heritage gig. Sure, he would like it if people wanted to hear new things from him, but that is fun, too.

It is time for Hawkes and Casey to catch the train if they are going to make their appointment. I walk with them towards the station and we talk about his gigging schedule. I also ask if his mole was real. He manages not to roll his eyes and says yes, but sometimes picture editors would flip his photos around, so it looked as if it moved. It has faded a bit, but when he points to it I can see it, under the stubble. I always knew it was real.

His daughter calls to ask how our interview went. He grins and says he will call her back in a bit, because he is still with me. They tell each other they love each another.

You really landed on your feet, I say; things could have gone a very different way. “Oh God, yeah – believe me, I know. And it wouldn’t have been good. I feel very, very lucky,” he says – and I believe him.

I wave him goodbye and watch him as he goes. And just as he always tried, he walks with dignity and pride.

The Complete Picture: The Albums 1991-2012 is out on 25 March