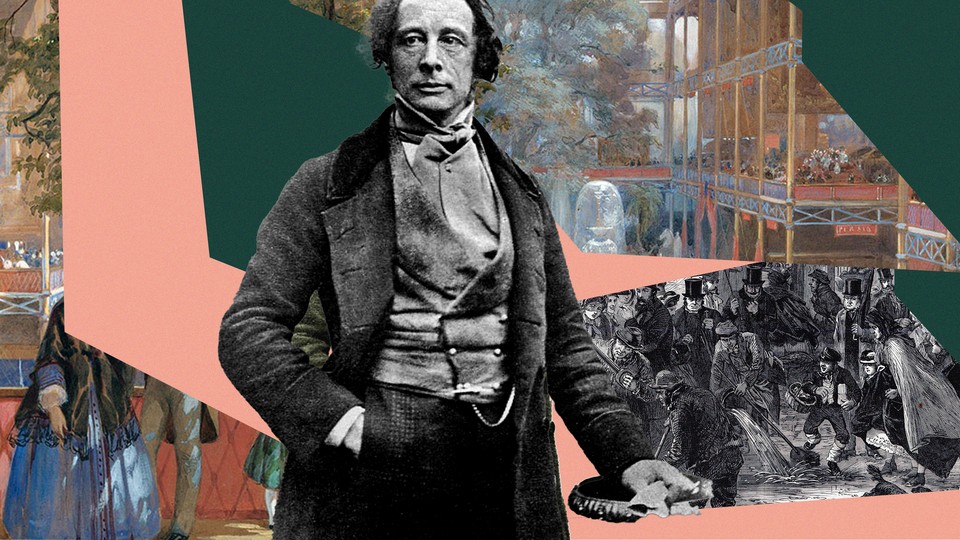

How Charles Dickens Made the Novel New

A new biography argues that the year 1851 marked an artistic renewal for the author.

Suppose Charles Dickens had died in 1850, at age 38—perhaps in a railway accident like the crash, in 1865, that killed 10 of his fellow passengers and left his nerves permanently frayed; or, more fantastically, from spontaneous combustion, as befell the booze-soaked rag seller in his 1853 novel, Bleak House.

He would still be famous, though perhaps less so than he is now. Readers left with only his early works would have eight full-length novels to savor, including The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and David Copperfield, as well as a tottering stack of novellas, stories, and travel writing. But our sense of Dickens, and the century that produced him, would be altered. We would notice his sentiment more, and his social mission less. His critical reputation would be less sturdy, and snobbish professors would dismiss him as largely a storyteller for children.

This did not happen. Unlike the many orphans, infants, and laborers who in his novels perish unloved and unwanted, Dickens lived on into middle age. And the events of 1851—the halfway point of the century, and of Dickens’s career—pressed him toward an artistic evolution. In that year he began writing Bleak House, in which he sought to capture, through formal and stylistic experimentation, the density and complexity of 19th-century London. The story unearths hidden connections among far-flung people (dancing teachers, detectives, street sweepers). A novel of networks, Bleak House offered its readers a powerful model for thinking about urban life: a new kind of literature for a new kind of world.

In The Turning Point, the literary scholar Robert Douglas-Fairhurst studies Dickens’s mid-career reinvention by zooming in on this single year, 1851. It was the year of the Great Exhibition in London. Marvels from around the world—an enormous diamond from India, saxophones from Paris—were displayed in the Crystal Palace, a colossal structure made of glass. (The young socialist polymath William Morris was reportedly so overcome by the exhibit’s crass materialism that he rushed from the glittering halls and vomited in the bushes.) Beyond the Crystal Palace, the world was becoming modern. The train and the telegraph made long distances feel short. Commentators hailed the progress of industry, as Britain’s robust manufacturing sector exported textiles, steam engines, and more. Yet the streets of London teemed with the starving and desperate. Raw sewage caked the banks of the Thames. Prescient British scientists warned that the destruction of tropical rainforests could yield “calamities for future generations.”

In response to an urbanizing world in which rapid material progress seemed to immiserate, rather than lift, the poor, Dickens developed a harsher and more experimental mode of writing. He had long been interested in social reform, and was a leading voice on problems of poverty and inequality—what Victorian men and women of letters called, rather grandly, the “condition of England.” In 1851, he was managing Urania Cottage, a home for “fallen women,” and editing Household Words, a journal of social commentary and fiction. (His powers of compassion were in important ways limited: He applauded the violent suppression of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and tried to have his wife, Catherine, placed in an asylum during their ugly separation.) Bleak House marked a turn toward a more mature and pessimistic social consciousness, inaugurating what one critic has called his “dark” novels. These dense and symbolic late works reflect his sorrow at the cruelties of his age. Plenty of political art fades into the annals of sociology. Dickens’s deepening confrontation with injustice, however, led to an artistic breakthrough.

Douglas-Fairhurst’s biography, stuffed with a curiosity shop’s worth of literary gossip and Victoriana, begins with the author in medias res. In 1851, having recently published David Copperfield, Dickens was casting around for his next big project. By this time, he was the most famous writer in England. But his reputation, Douglas-Fairhurst observes, was “surprisingly unstable,” dogged by critical skepticism. Some readers wondered if Dickens had “written himself out.”

In late November, Dickens began the work that became Bleak House, determined to wrest the chaotic realities of a world in flux into a narrative shape. Earlier industrial or “social-problem” novels by authors such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Benjamin Disraeli had aimed to document the suffering of workers and poor people; Dickens himself had presented a scorching critique of the Victorian workhouse system in Oliver Twist. With Bleak House, however, he sought to do something different: assimilate the new sensations of urban capitalism—marked by bewilderment, bureaucracy, and the collision of strangers—into a multi-plot novel.

Whereas two decades later George Eliot would produce, with Middlemarch, a novel of social connection that transcends, in its moral wisdom and psychological acuity, virtually any other work of Victorian realism, the task Dickens set himself in Bleak House was more ambitious in scale. He was taking an entire city as his subject. Little wonder, then, that he found it hard going. He complained to his friend and future biographer, John Forster, that he was laboring to “grind sparks out of this dull blade.” His manuscripts for Bleak House show evidence of painstaking corrections and reworking, unlike the easy fluency of his early novels.

Some authors find it necessary to maintain distance from the society they’re writing about. Dickens felt the opposite. The world he created in Bleak House arose from his enmeshment in the city of London and his familiarity with the streets on which he walked as many as 20 miles a day. From its first word—“LONDON”—Bleak House announces itself as a study of contemporary urban life.

The plot revolves around two primary narrative arcs: the mystery of the innocent Esther Summerson’s parentage, and the interminable lawsuit Jarndyce and Jarndyce, a matter of disputed inheritance. As is typical of Dickens, idiosyncratic minor characters and one-off comic set pieces provide much of the reading pleasure. Synthesizing several genres—the social-problem novel, the coming-of-age novel, the detective story—Bleak House stands as a landmark of Victorian realism, yet also opened the gates toward future literary experiments. In its critique of an impenetrable bureaucracy, the novel looks ahead to Franz Kafka. And its grotesque characters, its relish for parody, and its emphasis on problems of textual interpretation—illegible signs, mysterious legal documents, and other written artifacts proliferate in the novel—anticipate signature themes in the works of postmodern authors such as Thomas Pynchon and David Foster Wallace.

Bleak House acknowledges the confusion of industrial life, opening with its famous images of London fog. Yet it also offers a guide for how to think about the tangled web of the modern city. The novel discloses a vision of urban life in which everyone from the poor, degraded street sweeper Jo to the haughty aristocratic Lady Dedlock turns out to be tightly connected. (Jo’s smallpox infection is transmitted to Esther; Lady Dedlock is revealed to be closer to Esther than either of them knew.)

Through images of shared engulfment—fog, mud, disease—Dickens joined together seemingly disparate elements of modern life. He also presented an implicit case for social reform. By tracing the vectors that link various levels of society, such as disease, kinship, and the simple fact of shared residence in London, Dickens encouraged his readers to think of the rich and the poor as, in Douglas-Fairhurst’s summation, “parts of the same story.” Processing the chaos of London through a powerful and idiosyncratic imagination, he depicted a community bound together in a common fate.

Dickens once complained that without the buzzing life and teeming crowds of London, his imagination grew cramped. London, he wrote, was his “magic lantern”; his characters “seem disposed to stagnate without crowds about them.” Dickens needed the city, and the city needed Dickens. As we re-stitch urban life after two years of dislocation, Bleak House might reveal the secret principles that underlie the city as a system.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.