One of the most consistent ways in which award-winning journalist Noor Tagouri has been made to feel by the media is as a victim. As a hijab-wearing Muslim woman, who is committed to giving a voice to the marginalised, she has broken boundaries in a world marred by Islamophobia. She has hosted powerful podcasts and documentaries that get to the truth of the misrepresented and sidelined, and runs her own production company. There’s also her ISeeYou foundation, which she runs with her mother. She has been forced to endlessly defend her choice to wear a hijab. And yet, during a time where Muslim women are often wrongly lumped together under one collective experience of oppression and passivity, she has been left feeling like a victim because of societal stereotypes.

That’s not to say she hasn’t been victimised in her lifetime. Tagouri has been subjected to sexual violence and racism but, as she says herself, she stepped “out of that storyline” a long time ago. “In the past, I have adopted a victim conscience or mindset that was definitely put on me by mainstream media, when people ask me questions that come from this victim place - things like, ‘You’ve been through a lot, how does that make you feel?’” she says. “I would fall into that question and answer the way people wanted me to. The story I began to tell myself is that my story isn’t valid unless it comes from a place of oppression to success.”

She has worked through these issues to become more clear-sighted about who she is and what she stands for. “I do believe that we are all responsible for our healing,” she says. “If you choose to stand in a mindset that keeps you in a certain way, in a place of self-deprecation and self-doubt, I would ask, ‘is that story serving you?’ So often it’s not, and when you step out of that storyline, the world opens up. That’s where I’m at right now.”

Over the last 10 years, Tagouri has become the epitome of a modern firebrand journalist. She moves between podcasts and documentaries to social media and branded campaigns (her latest is for jewellery label Mejuri). Her podcast series on sex trafficking in the US, Sold in America: Inside Our Nation’s Sex Trade, won a Gracies Award in 2019 for Best Investigative Series. She has a big personality, and talks quickly, emphatically and passionately about the issues she knows a lot about and asks questions about the things she doesn’t. She steers clear of platforms that don’t offer the space for context and nuance because it stops her from being able to tell stories with depth and accuracy - and that includes Twitter. “I had this idea to tweet something that was silly and fine, and I went into a spiral about how it might be misconstrued and I decided not to post at all,” she laughs. “Later, I realised that the feeling I had was about not wanting to participate in conversations that lack context.”

“People have these very visceral responses to things without having the full picture of the story,” she adds. “It’s not good for our bodies or minds - why are we having these massive reactions to things we haven’t even thought through ourselves?”

Having an opinion, whether you know much about the issue at hand or not, has become a consequence of social media. It’s become a way of showing that we are informed, that we read the news and are alive to what’s happening in the world. Knowing when to speak up and when to listen is key, says Tagouri. “I have accepted that I don’t have to have an opinion on everything, I don’t want to and I don’t need to. I pretty much stopped posting about events that everyone felt pressured to post about. Why would I take up space to comment on something when I could just amplify someone else who is actually part of that experience who is already talking about it?”

Tagouri has been telling stories since she was old enough to talk. Growing up as the eldest of five children to Libyan parents in a small town in Southern Maryland, Virginia, US, her father would jokingly poke a camera in her face and ask her to tell him her news. She asked questions constantly and loved talking to people. Oprah was her hero. When she was 12, her dad told her that there was a name for what she wanted to be - a journalist. After completing a degree in journalism at the University of Maryland, she questioned her tutors who made her feel that she would never be able to remain objective because of her decision to wear a hijab. “What makes a good journalist is a person who is committed to witnessing a story before telling it,” she says. “This means that when you have an intention to tell a story, before you decide to write any part of it, you witness your intention play out. That story will always be far more impactful than the one you’ve already written.”

Her forthcoming podcast series, which has been three years in the making, explores the misrepresentation of the Muslim community and the impact of 9/11 on Muslim Americans. “This project, I feel in the depths of my soul, will change the world,” she says. We talk about news coverage that she’s been reading from 1986 as research. “It’s all the same stories that we’re still covering. There is so much demonisation and fear injected into the stories that we tell, so we’re constantly living in a state of fear, anxiety and terror. People have died of misrepresentation and misinformation. We have’t gotten out of decade-old thought loops.”

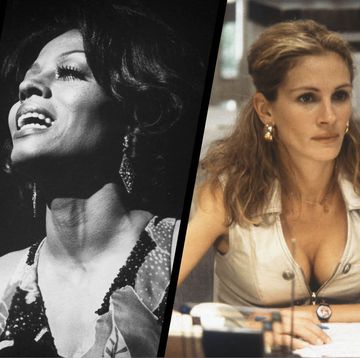

Tagouri also stars in Mejuri’s annual International Women’s Day campaign, alongside actress Tommy Dorfman and Olympian Allyson Felix. The label has also teamed up with one of Tagouri’s friends, Jenna Lyons, to create a new take on the signet ring. She's long been part of the fashion circle and is a regular on the Prada front row. Monse, Prabal Gurung and Brandon Maxwell are all style favourites. “It’s always been important to me to acknowledge that we often wear our stories even if we don’t realise it,” says Tagouri. “Throughout my life, fashion was another avenue to express my identity, an identity that was and still is evolving.”

Fashion is one of the many industries that been criticised over the last 18 months over its lack of diversity. If we really want to make lasting, penetrative change, she says, then we must revise the stories we’re telling. “Fashion is a form of a communication. When a trend is set, picked up and followed around the entire world, we’re telling each other, in one form or another, that we see each other, that we follow each other, that we’re connecting with each other. When you’re able to pull out stories within those patterns, you’re able to connect to people. When you’re able to connect people, representation happens a lot more naturally.”

As our conversation comes to a close, I ask Tagouri what she does to relax. As someone who dedicates her professional life to giving silenced communities a chance to be heard and understood, how does she switch off? Her answer (and very real enthusiasm for it) surprises me. “Birdwatching - I use binoculars and everything,” she laughs. “My husband and I moved up to the mountains in the Catskills a few years ago. I sit outside a lot and the birds are really loud, so I built a sun room. I think you’re witnessing a miracle every time you see a bird. The colour of them, too. If you were to say to me what makes you believe in god, I would say the colours of birds. I love to witness life and birds do that for me.”

Even in her downtime, Tagouri is still curiously observing and eagerly drinking up the living world. A journalist’s work is never done.