Padres prospect Steven Wilson among players caught in middle of MLB lockout

Padres reliever Steven Wilson signed for $5,000, made less than $20,000 last year and now drives for Uber to make ends meet during baseball’s lockout

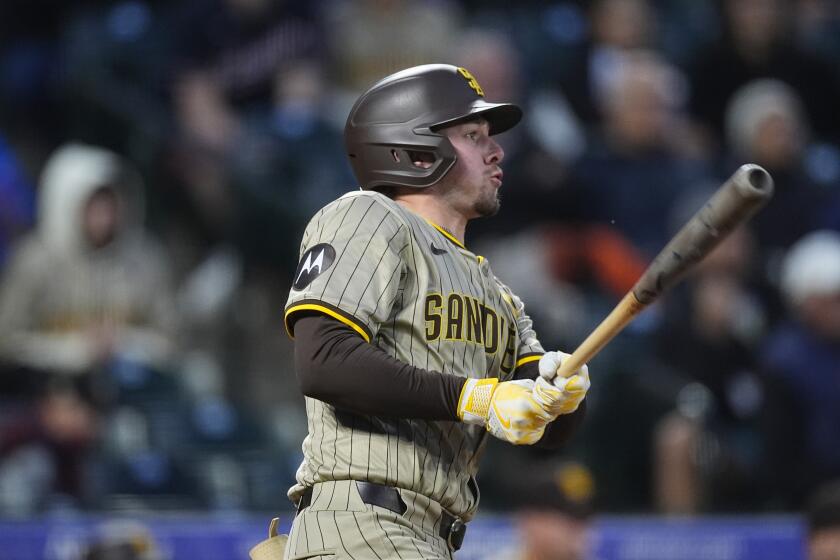

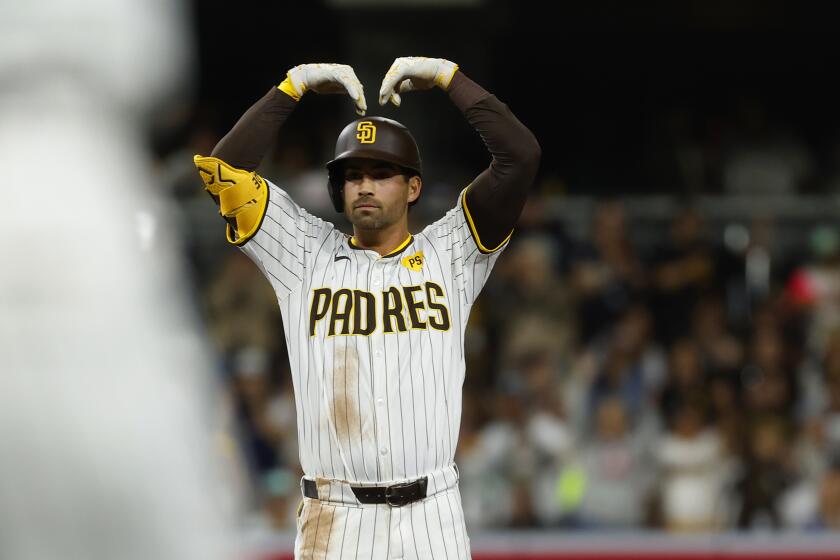

Because Steven Wilson lost his freshman season at Santa Clara to a shoulder injury and another season to Tommy John surgery, he had to settle for a $5,000 signing bonus as a sixth-year senior when the Padres drafted him in the eighth round in 2018.

He earned some $10,000 the following year in pro ball, less than that in 2020 at the COVID-19 alternate site and about $18,000 last year at Triple-A El Paso, where he officially, finally, pitched himself into the Padres’ 40-man roster plans and an opportunity to earn some real money.

One problem: Baseball’s owners locked out their players weeks after Wilson learned of the promotion while pitching in the Dominican Republic, forcing the 27-year-old reliever to again tap the Uber app on his phone to make ends meet.

This is not a complaint, Wilson reiterates.

It’s simply a reality for hundreds of players caught in the middle of the ninth labor stoppage in the sport’s history.

“Obviously I want to be playing and I want to be getting a paycheck,” Wilson said. “I haven’t gotten a paycheck from the Padres since October, so it’d be nice to get a paycheck from my employer. But I can see the bigger picture.

“ … I see what the players are fighting for and I’m on board with that.”

So instead of pushing for a job in the Padres’ big-league bullpen the last few weeks, Wilson has been juggling his training and throwing program at a nearby baseball facility while Ubering and delivering food in freezing temperatures in and around Littleton, Colo. Had he not been fortunate enough to land a spot on the 40-man roster, Wilson could have at least reported to Peoria, Ariz., for the start of the Padres’ minor league camp on Saturday. Instead he is among the 1,200 players waiting in limbo after Commissioner Rob Manfred canceled the first two series of the season after another stalled round of negotiations.

Even baseball’s class of have-nots can be further divided into haves and have-nots.

New to the 40-man roster like Wilson, Padres left-hander MacKenzie Gore signed for $6.7 million as the No. 3 overall pick in the 2017 draft before he was dispatched into the minor leagues. Even infielder Eguy Rosario ($300,000), also new to the Padres’ 40-man roster, received considerably more than Wilson, an economics major who went on to complete a masters in business analytics after accepting the Padres’ $5,000 signing bonus.

That was less than 3 percent of the $175,400 recommended for the 231st player selected in the 2018 draft but common practice when draft-eligible players can’t leverage their bonus against the prospect of returning to school for another year.

Wilson did have another option: a job offer with sports analytics company Rapsodo in St. Louis.

“I didn’t do it for the money,” Wilson said. “If I was doing things for money, I probably would have taken that job coming out of Santa Clara.”

Instead, Wilson began his climb up the Padres’ system, stockpiling for the grind of each season with rent-free offseason housing with his mother and winter jobs in coaching, retail at Lululemon and as an Uber driver. After he received his last check from the Padres in October and his last winter ball check from the Escogido club in the Dominican Republic in December, Wilson again turned to Uber to make ends meet in the early weeks of the lockout.

Which was fine until following a bullpen and a weightlifting session in January with a six-hour series of Uber drives and food deliveries led to his back tightening up the next day.

Luckily for Wilson, the Major League Baseball Players Association began offering monthly $5,000 stipends to 40-man players in February, essentially an advance on licensing revenue that players, based on games played in the majors, receive each spring. The money available is expected to jump to $15,000 a month in April.

For now, that money is helping Wilson at a time when spring training housing is usually covered by the Padres.

Of course, until this season — with MLB announcing a new policy providing housing to more than 90 percent of minor leaguers — the housing options and quality of meals provided to minor leaguers varied wildly from organization to organization. Major League Baseball also raised minor league salaries in 2021 — from $290 a month in Single-A to $500, $350 to $600 in Double-A and $502 to $700 in Triple-A — albeit a year after eliminating 42 teams and hundreds of playing jobs from its player development structure. MLB continues to argue that minor leaguers should not receive pay during spring training, on top of providing meals and housing, because the players are trainees.

None of this is part of the MLBPA’s fight.

The union is squarely focused on getting players on 40-man rosters paid earlier in their careers.

According to Spotrac, which tracks player contracts across all major sports, MLB revenue increased 30 percent from 2015 through 2019, jumping from $8.2 billion to $10.7 billion. Over that same time period, the average player salary fell from $4.45 million to $4.17 million and the median salary dropped from $1.65 million to $1.15 million.

Even those numbers are propped up by the headline-grabbing multimillion deals earned by the likes of Max Scherzer ($43.3 million annually over his new three-year deal with the Mets), Manny Machado ($30 million in 2022) and Eric Hosmer ($20 million in 2022). After all, 41 percent of the 1,400 players who accrued service time in 2021, according to Spotrac, earned less than $1 million as clubs have the right to set salaries for any player with less than three years in the majors.

The MLB proposal players rejected this week would have raised the league minimum from $563,500 in 2021 to $700,000, not far off the union’s request for $725,000. One major sticking point in negotiations, however, is a luxury tax that has morphed into something of a salary cap. The union is asking for the number to start at $238 million and rise to $263 million over the next five years. MLB has offered a growth rate that starts at $220 million and grows to $230 million.

Only the Dodgers and Padres passed the $210 million threshold in 2021, while traditional big spenders like the Yankees and Red Sox remained below the penalty line. With MLB pushing for expanded playoffs and more television payoffs, players argue there isn’t much incentive for owners to keep up with the top spenders in constructing playoff-caliber teams, further squeezing a middle class of players often cast aside in free agency in favor of prospects on rookie contracts.

Yes, Wilson would be in a lot better spot personally now if he was pitching on that rookie contract next month in San Diego.

That big picture: The union is fighting for the future he wants in this game.

“Being in an organization when you’re in the minor leagues,” Wilson said, “you understand that, hey, maybe (owners) don’t always have the best interest of players (in mind), like the way minor leaguers have been treated or the fact that they get paid how they get paid. I knew what I signed up for when I got in it. I was chasing a dream, so I understood it. I never complained about it.

“But when you look at the numbers and you look at the math, (owners) have the ability to treat guys better and they choose not to.

“It’s all just a choice.”

Go deeper inside the Padres

Get our free Padres Daily newsletter, free to your inbox every day of the season.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.