News

The Appalachian legacy of Carter G. Woodson, ‘father of Black History Month’

By: Curtis Tate | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

HUNTINGTON, W. Va. (OVR) — Carter G. Woodson was one of the first people to seriously study and document the history of Black people in the United States, and he also created educational programs that celebrated Black culture, most notably Black History Month. But few people know about his ties to Appalachia, where he spent much of his youth.

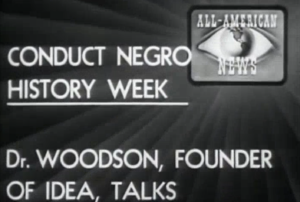

One of the few video recordings of Woodson speaking is included in the Library of Congress–part of a newsreel called All American News, which was produced for Black audiences in the 1940s and 50s to encourage support for the war effort.

The reel from 1945 commemorates the anniversary of the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery, and a barely audible Woodson urges Black people to celebrate Negro History Week – the precursor to Black History Month.

“What has the Negro to celebrate?” says Woodson, then 70. “They were brave soldiers during the colonial period, the American Revolution, the second war with England.”

Woodson spent most of his adult life in Washington, D.C., but he was born in Virginia and lived in West Virginia as a young man.

He worked in the coal mines in the New River Gorge in West Virginia and he attended the all-Black Frederick Douglass High School in Huntington, where he later became principal.

Cicero Fain, visiting diversity scholar at Marshall University, said the school was a “centerpiece of Black intellectual engagement.” Woodson and other Black people gravitated to such institutions out of necessity, he said.

“It’s clear that Black people – their primary goal was to establish their own institutions, their own networks that allowed them to operate within a racialized environment to move their people forward as best they could,” Fain said. “Because they really couldn’t count on white support.”

Woodson attended and became a dean at West Virginia Collegiate Institute, which was later renamed West Virginia State University. He then enrolled at Berea College in Kentucky, the first in the South to integrate.

Jessica Klanderud, the director of the Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education at Berea, says Woodson’s ties to Appalachia aren’t widely known in part because he wrote little about himself in spite of his extensive scholarship.

“He was never big on biography,” she said.

Klanderud says Woodson was not on-campus full time because he was still working as a principal in West Virginia while he studied.

“He was teaching, he was educating Black students, and all of that was part of his time in Appalachia,” she said.

Woodson’s time was cut short in Berea. He left in 1903, the year before the Kentucky legislature passed a racist law banning Black and white students from receiving an education at the same school.

Klanderud says it’s hard to know if segregation pushed Woodson out of Kentucky, but he finished his studies through correspondence while living in Chicago.

“So it’s possible that he sort of saw the writing on the wall and decided that, you know, he needed to be wrapping up his time at Berea,” she said.

Woodson went on to get degrees at the University of Chicago and Harvard, but Klanderud says he continued to correspond with people at Berea and spoke fondly of his time there.

He became the second African-American to receive a doctorate from Harvard, the first being W.E.B. DuBois.

Woodson later wrote that to his dismay, his professors at Harvard showed little interest in the contributions of Black Americans beyond enslavement. He founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, which began Negro History Week in 1926 in honor of the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. In 1976, Black History Week became Black History Month.

This year’s Black History Month comes at a time when state legislatures, including lawmakers in West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio, are debating legislation to limit what public schools can teach about Black history and the history of racism in America.

Fain said that wouldn’t sit well with Woodson.

“His whole goal was not to demonize white America,” he said. “His goal was to elevate Black contributions and experiences. Black History Month is not about demonizing white people. It’s about providing an opportunity to chronicle, acknowledge and celebrate the Black experience in this country.”

Fain noted that Woodson’s most popular book, “The Miseducation of the Negro,” called out an educational system that made Black Americans’ contributions and experiences invisible. It called on Black people to learn about their own history.

“I think Carter G. Woodson would be greatly dismayed at these legislative attempts that are now taking place,” Fain said.

Though Woodson didn’t live to see the end of Jim Crow, Klanderud says he left a big imprint on education.

“The legacy he left was so robust, but it’s hard to know if he felt that at the time,” she said.

Kentucky amended its segregationist education law in 1950, just after Woodson died, to allow colleges to integrate. Segregation schemes would be rendered illegal across the country after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954.