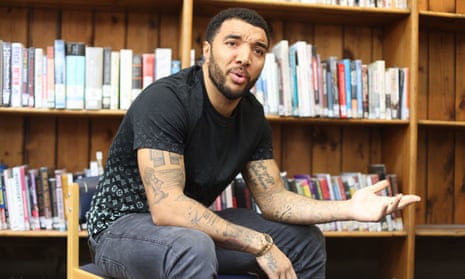

The footballer Troy Deeney, who still receives regular racist abuse and who has three children in the UK education system, has called for Black experiences to be properly taught in class. It’s an issue I’ve long campaigned for.

Back in 2020, during the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, petitions were sent to the then education secretary, Gavin Williamson, for the national curriculum in England to include examples of Black history. The petition set up by my organisation, The Black Curriculum, gained more than 200,000 signatures.

But these calls went largely ignored. The government said there were already enough examples of Black history in the national curriculum, and that schools were free to teach what they want. Many schools at this time, which were seeking guidance around how to teach Black history, contacted us. It was particularly clear to us that many teachers lacked confidence in how officials within their education department would respond. This is why Deeney’s latest calls are vital, and why the new education secretary, Nadhim Zahawi, must treat this as a priority.

Sadly, the teaching of Black history has been caught up in culture-war politics, with MPs and ministers wrongly claiming it means “cancelling” historically significant white figures. In October 2020, the equalities minister, Kemi Badenoch, told parliament: “The government does not want children being taught about white privilege and their inherited racial guilt.” Shortly afterwards, Liz Truss, then also an equalities minister, said of her schooldays: “While we were taught about racism and sexism, there was too little time spent making sure everyone could read and write.”

But Black history should be a mission for all of us, whatever our politics, because to truly “level up” our society requires a rich, full-spectrum educational experience for all students.

The benefits of inclusive teaching that acknowledges the impact of Black people across all subjects are tangible and long term for all students – for Black pupils, of course, but also for every child whose only knowledge of Black history is enslavement. This is about building a sense of identity and belonging, bringing in all young people and fostering social cohesion all year round – not just in Black History Month. By fostering greater understanding, empathy and knowledge, we are less likely to have negative perceptions that can have damaging consequences – such as the lowering of grades, exclusions, racist incidents and other systemic society issues.

Deeney himself commissioned a YouGov poll, which showed that only 12% of teachers across primary and secondary schools in England feel empowered to teach optional topics around Black history. These topics – including colonialism, migration and identity – cannot be taught without the necessary guidance and accompanying material. If these are lacking, then children are being failed, and the survey found that. Most teachers (64%) felt they were not provided with enough ongoing training and personal development in this area.

During 2021 alone, my organisation provided 6,000 teachers across the country with training in Black history: it is imperative that teachers are supported and don’t fear they’ll be put in compromising situations by teaching this subject.

Yet recent government intervention in relation to Brighton and Hove’s anti-racist training – where the council was accused of telling schools to teach white privilege and inherited racial guilt to children – discourages schools from teaching history in a more accurate and truthful way. Teachers in our training sessions have revealed how they fear being accused of breaking the equalities law for simply teaching Black history. In a modern, multicultural country this cannot be right.

Deeney, who we’ve been only too happy to work with over the past few months, has now stepped up his campaign to change the national curriculum. Following the adoption of an inclusive curriculum in Wales, we want to see England’s curriculum shaped around reality, we want teachers in all areas of the country, whether in primary or secondary, to have Black histories embedded in their teaching.

Deeney is more than a footballer with a cause: he represents a key shift in British education. Our schools system is just a microcosm of wider society, and we now have an opportunity to make a permanent change by teaching the stories of all our people.

Lavinya Stennett is founder and chief executive of The Black Curriculum