Last year, Grateful Dead singer and rhythm guitarist Bob Weir reunited with his long-lost bandmate, Jerry Garcia.

“He wanted to introduce me to a song,” Weir, 74, recently recounted of a dream he‘d had. “He invited the song into the room and it had the look and feel of an English sheepdog. It was about the size of the room. It was enormous, but you could see through it.

“The song came up and sniffed me,” Weir continues, speaking by phone from his home in Mill Valley, Calif. “We got to know each other and be friends. Then, as it turns out, it was a jazz ballad that Jerry and I were going to sing, and it was a duet.”

The ballad, however, wasn’t quite ready for the waking world — Weir didn’t have a melody or chords to show for it. “I’m still reaching for that,” he says. “I’m going to have another installment on that dream, I think.”

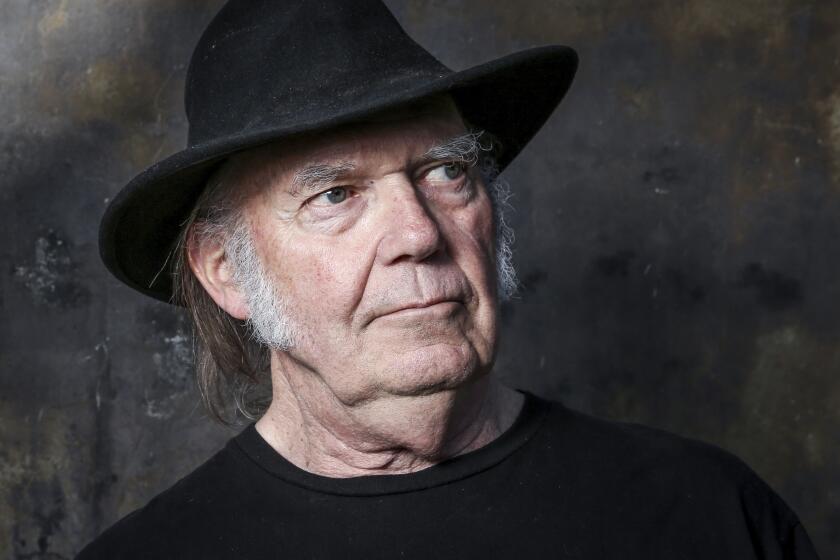

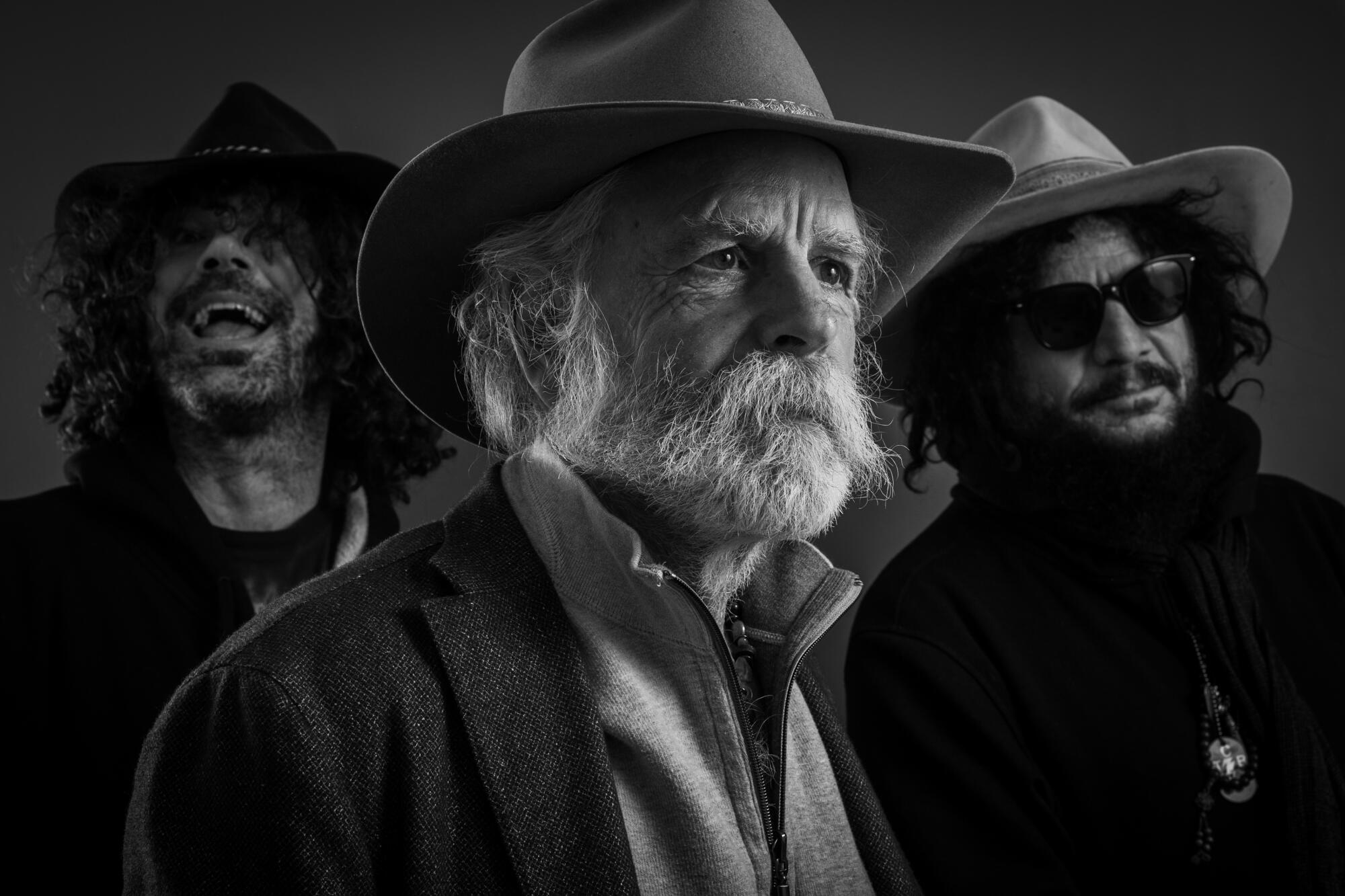

Garcia has been dead for 27 years but the psychedelic dream of long and winding jams and cockeyed harmonies lives on, and not just in Weir’s sleep. A new album, “Bobby Weir and Wolf Bros: Live in Colorado,” set for release on Feb. 18, is the latest incarnation of the many Dead-related projects that have blossomed since the Grateful Dead ended, including, variously, Dead & Company, Further, Phil Lesh and Friends, and Weir’s onetime side project, Rat Dog.

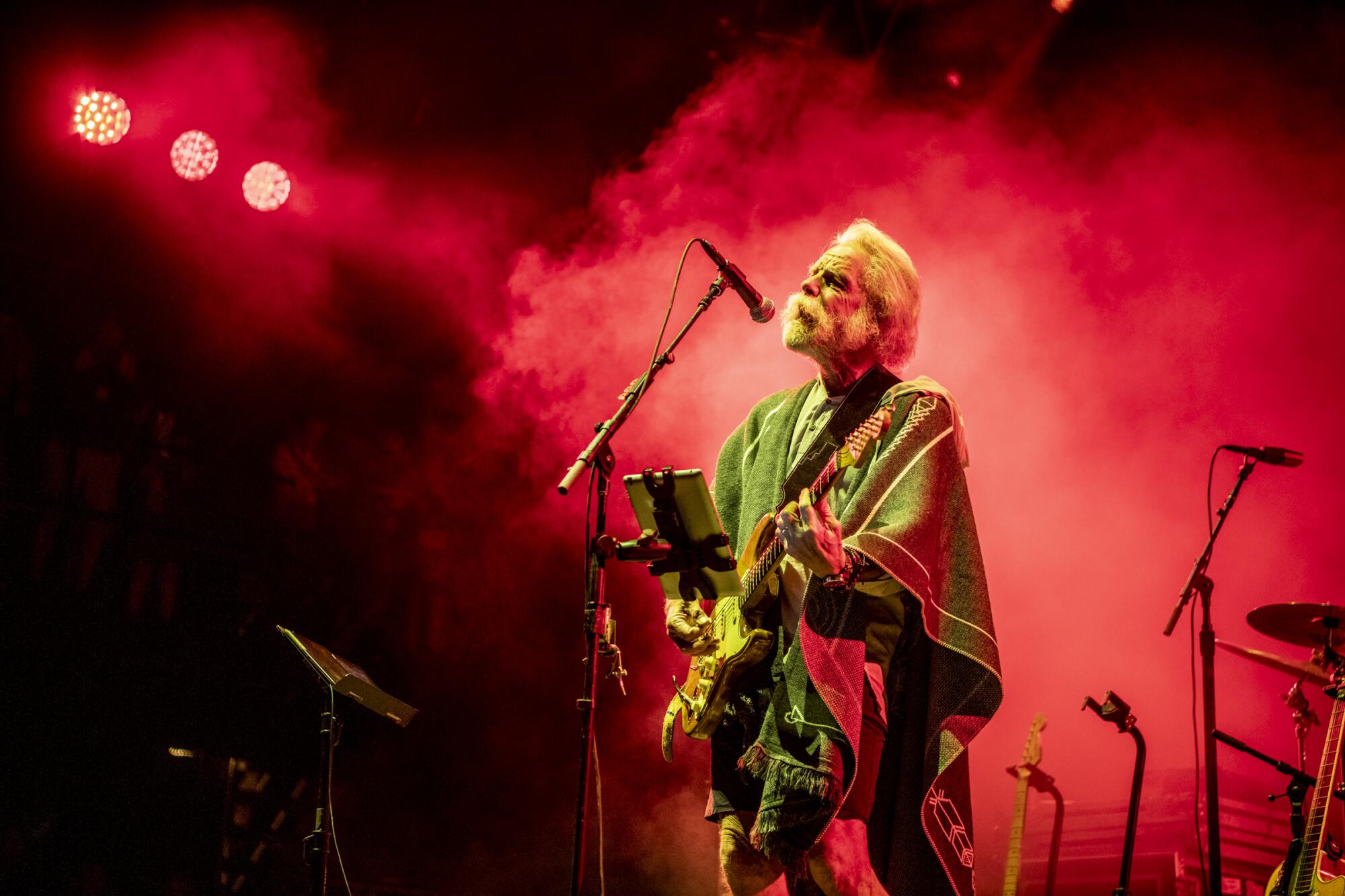

Weir formed the Wolf Bros four years ago as a trio, with bassist Don Was and drummer Jay Lane, and has expanded to include keyboards, a pedal steel guitar player and a horn section Weir dubbed the Wolfpack. “Live in Colorado” documents the moment Weir began playing to live crowds again last June. The Wolf Bros, Weir says, are a vehicle not only for further jamming but for helping develop and burnish the Dead’s classic repertoire. “The songs, they grow, they mature,” he says. “They evolve over the years, and they’re nowhere near done doing that. I’m just trying to give them every opportunity to continue to do that in as many different ways as they feel comfortable going or doing.”

The new album opens with “New Speedway Boogie,” which the Dead originally recorded in 1970, and the song’s familiar riff is met with an emotional crowd roar. “There was a triumph of having survived this plague,” says Was, the Grammy-winning producer and president of venerable jazz label Blue Note. “The audience was so glad and relieved to be back at a concert, and to be alive, that it was quite moving.”

Wolf Bros have the loose and loping feel of classic Dead, but with tighter and less shambolic musicianship backing Weir’s singing, which can be, for the uninitiated, an acquired taste. His youthful yelp has taken on a sandpapered growl, but on songs like “Big River,” the Johnny Cash song the Dead began covering in 1971, Weir leans into his weathered voice and has fun with cornpone phrasing: “I’m going to sit right haaare until I die…”

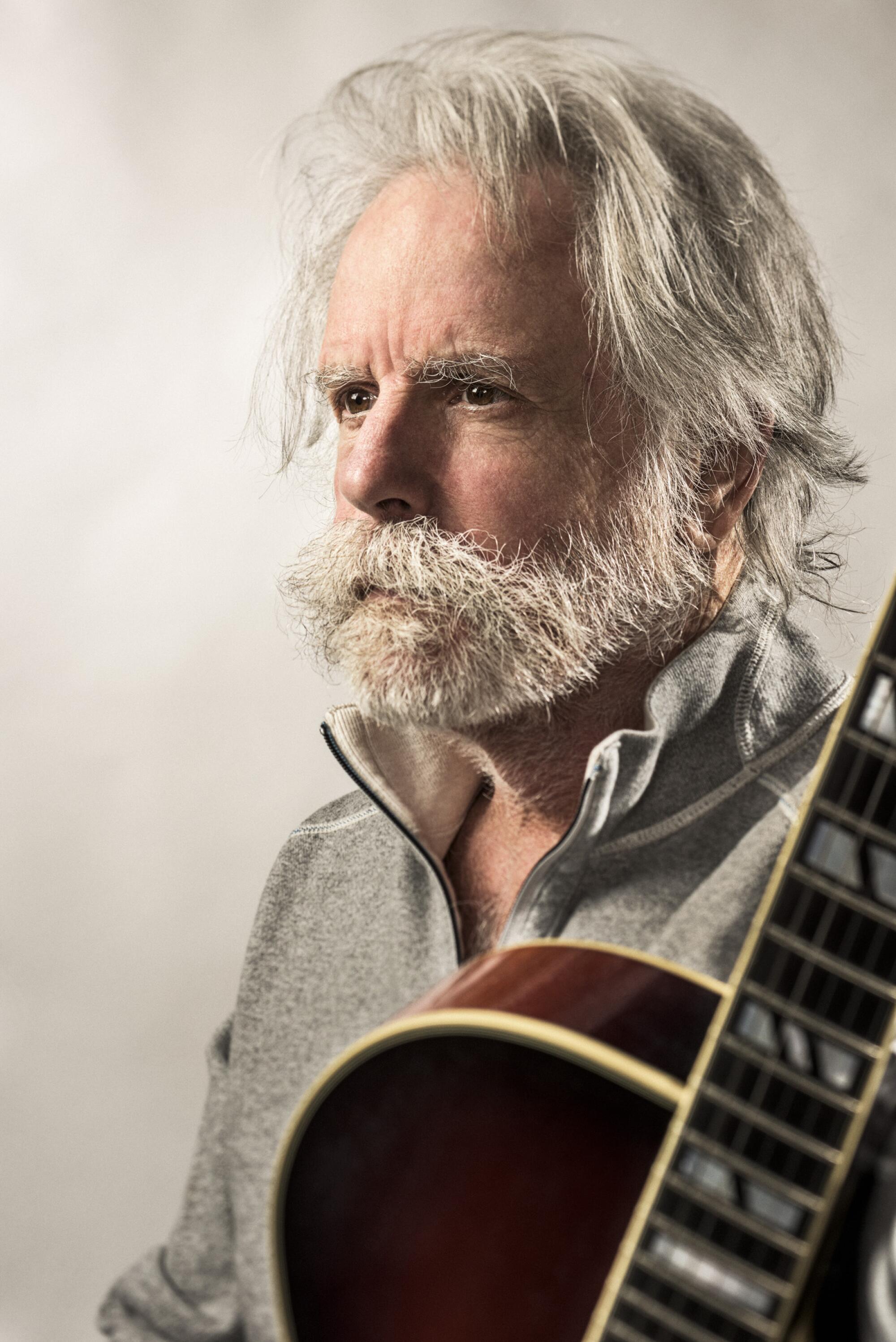

That lyric has a special resonance. Always the youngest (and best looking) in the Grateful Dead — “Beautiful Bobby surrounded by the ugly brothers,” the band used to joke — Weir has taken on the mantle of elder statesman, growing a Yosemite-Sam-size mustache that’s becoming nearly as iconic as Garcia’s beard. When bassist Lesh retired from full-time touring in 2014, Weir became the de facto flame keeper of the Dead’s legacy, soldiering on with John Mayer as lead guitarist. He began conceiving the Wolf Bros after the death of Rat Dog bassist Rob Wasserman in 2016. Naturally, the whole idea, including the name, began with a dream. “I woke, and I picked up my phone and I called Don,” says Weir. “I said, ‘Listen, I just had a dream. You want to do this?’ And [Was] said, ‘Sure.’”

Was first saw the Grateful Dead in his hometown of Detroit in 1971 and befriended Weir in the 1990s. To audition, Weir asked him to learn 10 Dead songs. Was practiced feverishly — only to have Weir launch into completely different songs at the tryout. No matter: “In the first 60 seconds we knew it was going to work,” says Was. “We jammed for 20 minutes and he got his cellphone out and called [manager] Bernie Cahill, ‘We’re doing this, let’s book it.’”

Weir says he wanted a simpler, nimbler version of previous groups he’s been in, one that would allow him to stretch out on guitar (he says Lesh’s busy bass playing took up a lot of space) and that could add or subtract members to achieve different ends. “We can plug one, two, three or 90 people in, and we’re doing any and all of that,” he says.

As if to stress-test the concept, Weir is adding the National Symphony Orchestra to the band for a program of lushly appointed performances of Dead material. The idea first took root in 2011 when the Marin Symphony Orchestra approached him for a one-night-only show in San Rafael. The arrangements — for songs like “Jack Straw,” “Uncle John’s Band” and “Playing in the Band” — will be part of the orchestral repertoire Weir will premiere later this year at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. Weir says the fullness of strings and brass was something the Dead had always been reaching for but never had the instrumentation to achieve. “It’s just that we didn’t have the voices, in many cases, to hit some of those notes,” he says.

Performing with an orchestra presents some challenges: classical players follow charts, which doesn’t leave a lot of wiggle room for psychedelic meanders. But Weir, ever ambitious, is working with arranger Giancarlo Aquilanti, who teaches music theory and composition at Stanford University (and who helped orchestrate the original Marin event), to invent strategies for allowing an orchestra to improvise too. For instance, the conductor can cue specific members or sections of the orchestra, a clarinet or strings, to improvise on the fly. Weir says they might communicate through iPads. “If this works for this piece, it’ll work for any composer,” Weir says. “Haydn, Mozart, Stravinsky — you can do this with any piece of music.”

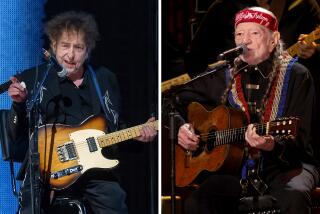

Young’s new remarks come two weeks after the singer pulled his entire catalog from the streaming service in protest of Rogan’s dalliances with vaccine misinformation.

Aquilanti, who grew up in Italy, wasn’t “fully introduced” to the Dead’s music until he met Weir. He stresses that these aren’t merely symphonic arrangements of the Dead’s music but an attempt to integrate a classical orchestra into the jammy spirit of the band. So far, he’s drawn up 650 pages of score that add up to three hours of music. “There is a component of unknownness,” he says. “This is not an arrangement where you know exactly what’s going to happen. For better or worse, we’re trying to do something new.”

It’s all part of Weir’s project to give the Grateful Dead catalog a life beyond the band. “We’re trying to give it a place to hang its hat for the next two or three hundred years,” he says.

Weir’s late-life renaissance doesn’t end at symphonies. In addition to the Wolf Bros, who will begin touring in March, he’s developing both a musical he wrote with Taj Mahal (about baseball legend Satchel Paige) and an opera he hopes to debut at the Grand Ole Opry in the next few years.

The opera idea came about while he was trying to write a country record in Nashville. He witnessed a lunar eclipse one night and dramatically altered course. “I was sitting on the lawn out in front of the studio there watching the full eclipse,” he says. “I was just sort of in a state of wonderment about how all this music had come out of the heavens, and I was just, ‘How the hell did that happen?’ It’s like something slapped me on the back of the head. I could almost feel it, and I said, ‘That’s because you’re working on an opera, stupid.’”

Last year, Weir surprised a lot of fans by joining TikTok, producing short videos of himself working out before shows, swinging kettlebells and doing lunges with TRX bands. (The head of his security detail is his trainer, and Weir recently outlined his exercise regimen in Men’s Health magazine.) Weir’s college-age daughters introduced him to the platform and he plans to use it to demo a product he dreamed up: a face covering for fans attending indoor concerts during COVID. While scrolling through Instagram, Weir says, the “artificial intelligence sent me a little ad for a Japanese headband/scarf. I looked at that thing, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘Now wait a minute, that’d make a decent mask with a couple of changes.’”

It’s a weird moment to be a 1960s icon, as contemporaries like Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones and Mike Nesmith of the Monkees slip away, while living ones, like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, tap back into their protest roots, battling Spotify over podcaster Joe Rogan’s COVID misinformation. Times have changed, but Weir believes music may be the saving grace for a nation struggling with intractable division.

“I have a feeling that there’s not much that we agree on,” he says. “There’s the concept of American exceptionalism, I guess. I’m not sure that I buy that because there’s nothing particularly exceptional about this country’s drift toward fascism.

“But there is one thing that I do buy thoroughly,” he says, “That is that American music, as the world pretty much agrees, is exceptional. The elements of why that is are pretty clear and evident, that the African and European musical traditions that happened here on this continent made it possible. Hopefully, we can lean on the music to help pull us together.”

Weir clearly isn’t ready to be gratefully dead in the literal sense, though he’s surprisingly sanguine about his own mortality. “I have absolutely no fear of dying,” he says. “In fact, to look forward to it. In my view, death is the last and best reward for a life well-lived. But, that said, I still have a fair bit of life to live before I get there.”

Weir has been writing a much-anticipated memoir. He’s completed the first four chapters. “It’s where I’m just now meeting Jerry,” he says, meaning he’s only at New Year’s Eve, 1963. But he’s got other periods and stories fleshed out, he says, just not yet organized. The last chapter, of course, is one he’s still working out in real time. In addition to symphonies, operas and kettlebells, there’s that unwritten collaboration with Jerry Garcia — whenever the sheepdog decides to return.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.