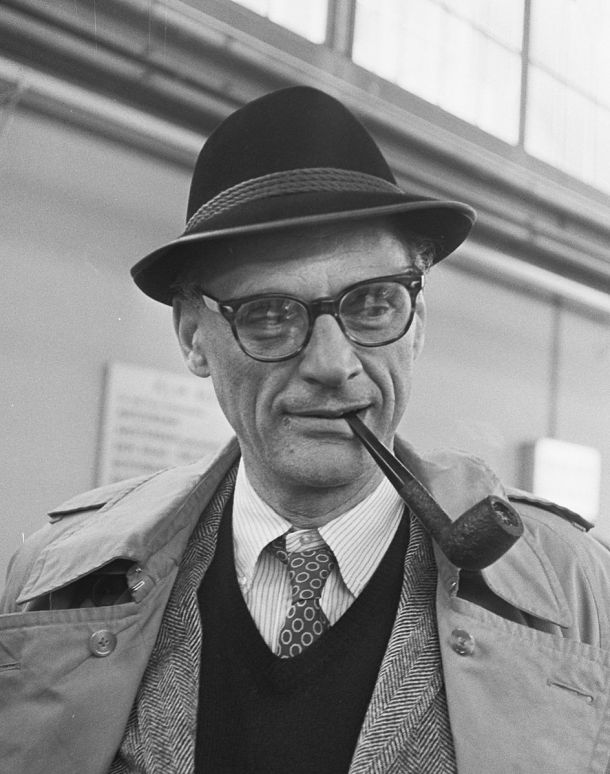

Writer Laurence Maslon highlights how Arthur Miller’s body of work scrutinized the “moral compass of American society.”

“Why do you not direct some of the magnificent ability you have to fighting against Communist conspiracies?” Arthur Miller was asked in the spring of 1956. “Why do you not direct your magnificent talents to that?”

The interrogator was not a drama critic or a news reporter: it was a congressman, a member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities and Miller, testifying before Congress, was literally in the hot seat.

Arthur Miller’s prospective answer—an unrecorded response to a rhetorical question—was important to the congressman because in 1956, Miller’s talents as a playwright were indeed recognized as “magnificent.” He was, along with Tennessee Williams, acknowledged as the most influential and successful playwright of the post-war age. But whereas Williams’s realm was the human psyche of the individual, Miller’s canvas was the moral compass of American society.

As he wrote, “The theater is a serious business, one that makes—or should make—man more human, which is to say less alone. [It involves] real questions of right and wrong. Then I set out, rather implacably, and in the most realistic situations I can find, to search out the moral dilemma and try to point a real, though hard, path out.”

Arthur Miller chose an extraordinary era in American culture to search out the moral dilemmas of his age and in an impressive run of more than two decades, he held the spotlight as the most quoted, profiled and admired playwright on Broadway, using the commercial theater as his bully pulpit. He dealt with the Depression in plays as diverse as “The Man Who Had All the Luck” (1944) and “The Price” (1968); World War II and its aftermath in “All My Sons” (1947); the post-war obsession with materialism in “Death of a Salesman” (1949); and the era of McCarthyism and political suppression in “The Crucible” (1953). Miller would continue to write plays and screenplays into the very beginning of the 21st century and was also a vocal supporter of freedom of expression in literature and the arts.

Perhaps his greatest talent was to create characters and situations that embodied conflict; when his leading characters were working out their internal contradictions, they became compelling metaphors for the troubled nation which Miller observed. Miller was, by his own admission, fascinated by “what exact part a man plays in his own fate.”

As he told American Masters executive producer Michael Kantor in a 1999 interview, “Ideally, it would be wonderful if audiences left the theater with a deeper understanding of themselves—a more vivid appreciation of life. A sense of a more real appreciation and by ‘more real,’ I don’t mean a documentary. I mean a confrontation with ultimate issues of life and death.”

“Death of a Salesman” was the most discussed and dissected play of its era (and it won every award in sight, including the Pulitzer Prize) and through the personal agony of its eponymous hero, salesman Willy Loman (who in Miller’s words was “alone, valueless, without even the elements of a human person, when once [he fails] to fit the patterns of efficiency”) he tackled the most vast canvas of all—the American Dream:

“The American Dream is the largely unacknowledged screen in front of which all American writing plays itself out—the screen of the perfectibility of man. Whoever is writing in the United States is using the American Dream as an ironical pole of his story. The American idea is that we think if we could only touch it, and live by it, there’s a natural order in favor of us, and that the object of a good life is to get connected with that live and abundant order. And it’s the failure in relation to that screen, that backdrop that pervades American writing. Including my own.”

How “patterns of efficiency” affect human dignity in the workplace is still a persistent theme, particularly in the post-pandemic culture. Sara Selevitch is a writer and server who works in Los Angeles; she wrote the following for the Washington Post on August 27, 2021: “I grew up in a blue-collar neighborhood, and I’ve long believed in the dignity of workers. I conflated that with the belief that hard work feels good and makes you a better person. These days, I wonder who benefits from the latter notion.” Miller observed this dilemma six decades earlier:

“Willy Loman is, I think, a person who embodies in himself some of the most terrible conflicts running through the streets of America today. A Gallup poll might reveal they are not the majority conflicts; I think they are.”

As the success of “Death of a Salesman” pushed Miller further into the cultural spotlight, his political stance came under greater scrutiny. The early 1950s were a time when progressive, liberal, or left-wing ideologies came under attack by institutional and governmental forces. It was also the age of the re-emergence of the House Committee on Un-American Activities and Senator Joseph McCarthy’s investigations into purported Communist influences in the government and entertainment fields; McCarthy gave his name to an era of mistrust, paranoia and persecution. As Miller put it: “It was not only the rise of ‘McCarthyism’ that moved me, but something that seemed much more weird and mysterious. It was the fact that a political, objective, knowledgeable campaign from the far right was capable of creating not only a terror, but a new subjective reality, a veritable mystique which was gradually assuming even a holy resonance…it was as though the whole country had been born anew, without a memory of certain elemental decencies which a year or two earlier no one would have imagined could be altered, let alone forgotten.”

The political became personal for Miller when his great collaborator, director Elia Kazan, agreed to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952. Miller, shaken and disillusioned, met with Kazan before driving to Salem, Massachusetts to do some research; he saw a parallel between contemporary America and the paranoia of the Salem Witch Trials: “‘The Crucible’ is a play that grew out of the 50s. It grew out of the wild, so often uncontrolled, accusations that were flying around and ruined a lot of people’s lives. I found a parallel in the terrible witch hunt which killed 19 people in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692.”

Miller was shocked at how quickly and how insistently his colleagues and friends had been cowed by the spurious hand of “justice.” In his introduction to his “Collected Plays,” Miller put it as neatly and as beautifully as any line in the play:

“Above all, above all horrors, I saw accepted the notion that conscience was no longer a private matter, but one of state administration. I saw men handing conscience to other men and thanking other men for the opportunity of doing so.”

“The Crucible” opened on Broadway in 1953 and had a mixed reception: “When McCarthy was around, the critics, reflecting the feeling in the audience, were quite simply in fear of the theme of the play.” When the play was revived Off-Broadway in 1958, the clouds of fear had dissipated and audiences could encounter the play on its own terms—along with “Salesman,” it has become Miller’s most produced play.

By the late 1950s, the intimidation instilled by the House Un-American Committee had transformed into a “photo op.” Miller’s passport application was rejected by the State Department in 1954 and in 1956, he was called to Washington to answer questions about his Communist affiliations. “By the time I got involved with it, it was really towards the last part of its power. To give you an idea of what their motives were, I was offered a deal: I wouldn’t have to testify at all or come at all if the chairman of the committee could be allowed to take a photograph with Marilyn Monroe, who I was just about to marry. Then he would call off the whole thing.”

Miller’s watchfulness about the state of our nation’s values rouses us to be vigilant against the ever-persistent incursion of paranoid politics:

“The opposite of paranoid politics is Law and good faith. An example, the best I know of, is the American constitution and the Bill of Rights.”

And he was bemused at the cycles of history—perhaps he’d be horrified at the American scene two decades after his death, but he certainly wouldn’t be surprised. Much like his idol, 19th century playwright Henrik Ibsen, he knew that human beings are simply the products of their times and as the past repeats itself, so do our responsibilities and culpability. As Miller wrote in the 1980s:

“From the heights of Wall Street, the Pentagon, the White House, big business, the same lesson seems to fly out at us—the past lives!—the explosive force when it bombs in the present, and above all, with the soul-rot that comes from the hypocrisy of its denial.”