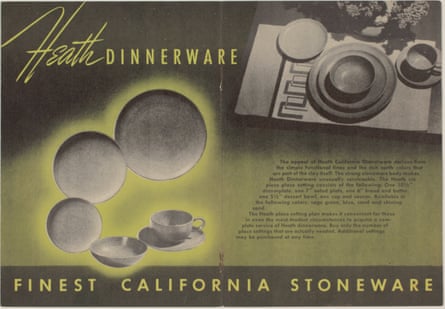

For 75 years, no firm has embodied the ethos of casually upscale California design quite like Heath Ceramics. Founded immediately after the second world war by Edith Heath, a largely self-taught ceramicist and potter, the company revolutionized domestic ceramics, transforming the art form from stuffy tea sets to versatile, modern dinnerware.

Now, a new exhibition co-curated by Heath expert Jennifer Volland and the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) celebrates Heath as a ceramicist, a chemist and an entrepreneur, one whose half-century career helped establish California as a site of mid-century modernism while elevating ceramics as a genre.

“I think of her as an alchemist,” said Drew Johnson, the curator of photography and visual culture at OMCA, where the exhibition – the first major, posthumous retrospective of her work – is taking place.

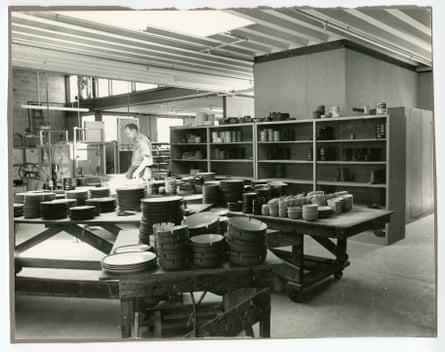

Johnson says that Heath’s playful style was the key to her experimental and ultimately revolutionary approach. “I think it comes from the idea that she was largely self-taught,” he says. “Most of her investigations into ceramic chemistry and glaze and the whole process of developing a clay body from raw clay into something she wanted — it was from her private experimentation, which was really rigorous.”

OMCA has been continuously displaying pieces of her work since its founding in the 1960s but the exhibition is its first to tackle a retrospective of Heath’s work. Juxtaposing vintage ashtray ads and vitrines full of low-rimmed Heath bowls, with illustrations of Heath’s fascination with the properties of clays found in the Sierra Nevada foothills, the show builds a portrait of a postwar Renaissance woman unafraid to upend notions of what ceramics could be.

Born into a Danish American family in Ida Grove, Iowa, in 1911, Heath moved to California when her husband Brian took a job with the Red Cross. Barely two years after she took her first ceramics class, she had already won her first solo show at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor, a success that she quickly parlayed into her own factory.

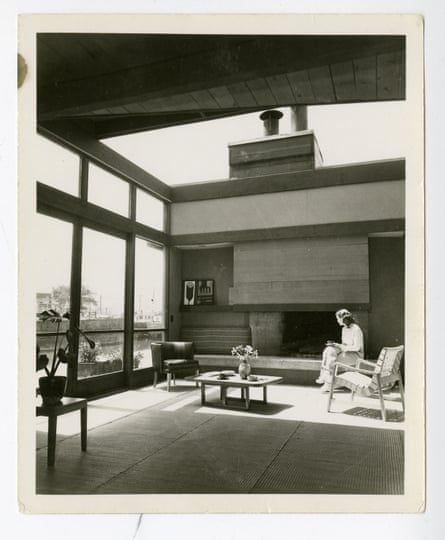

Based in Sausalito, an affluent and historically artsy enclave just across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, Heath Ceramics has long functioned on the same anti-aristocratic principles as the 1920s Bauhaus, using scientific principles to make design accessible to California’s burgeoning middle class. Some 75 years later, its quality and beauty may be all but universally beloved, but Heath has always had to reckon with a tension between idealism and price.

“Her stuff is expensive,” Johnson concedes. “It’s not cheap. And yet she was very public in saying she was an egalitarian designer, making works for a casual lifestyle that was informal and not for the elite. She would admit, ‘Yes, my stuff costs a little more than other people’s, but it will last a lifetime.”

She never ceased tinkering. Fascinated by eutectics, the science of mixing various metals into clay to alter its properties, the Heaths would drive around the west coast, gathering buckets of native clays to take home and experiment with. This stood in stark contrast to the craft’s centuries-long use of white clay, most of it imported.

“We do try to make the point of Edith as a rebel with the rejection of what had been traditionally used to make fine dinnerware,” Johnson says. “She said, ‘No, I’m going to use these native clays that evoke the landscape.’”

A product of the decomposed granite that makes up the Sierra, those hardy native clays had mostly been used for industrial applications, like pipes. Their ability to withstand high heat appealed to Heath, as did manganese, the metal that gives Heath pieces their signature speckles.

Initially, her work earned little love from the establishment. Its commercial allure – the upmarket San Francisco department store Gump’s was an early champion – offended what Johnson calls “arts potters”. Heath was also fundamentally agnostic on the merit of mechanical versus hand production, and her insistence that manufactured pieces developed from a handmade prototype could be just as aesthetically excellent as handmade pieces generated so much mutual antipathy that she was asked to leave the San Francisco Potters’ Association.

But as the years passed, her ideas and aesthetics proved ahead of their time. Today Heath plates and cups are staples at many Bay Area restaurants, as much a part of California’s vaunted food culture as seasonal produce.

The exhibition’s clearest demonstration of ceramics before and after Edith Heath comes in a side-by-side comparison of her family’s china with some of her own work. The former are bone-white and strikingly old fashioned, including a delicate, poppy-patterned teacup and saucer that look as though they belong in a well-to-do midwestern farmer’s parlor. Heath’s early Coupe Line, by contrast, has a warm hue and an oven-friendly durability that evokes the evolution of public taste from Wonder Bread to artisanal, sourdough loaves.

As her career progressed, Heath moved into tile and building materials, winning industrial-design awards for her experiments. After a 1991 firestorm in Oakland killed 25 people and destroyed thousands of homes, she developed new ideas for fire-resistant construction. By the time she died, in 2005, tastemakers had once again embraced the simple elegance of Heath’s aesthetic. As A Life in Clay proves, it remains an essential component of the Golden state’s relationship with postwar modernism – a key element of California living, baked in a kiln.

This article was amended on 1 February 2022. An earlier version described the OMCA show as the “first-ever solo exhibition of Heath’s career”. To clarify: it is the first major, posthumous retrospective of her work.

Edith Heath: A Life in Clay, is on display at the Oakland Museum of California from 29 January to 30 October 2022