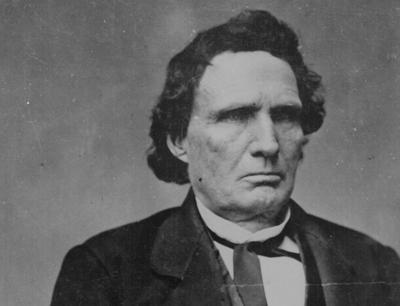

THE ISSUE: “James Buchanan and Thaddeus Stevens — Lancaster’s best-known politicians of the 19th century — have never been treated equally in their adopted home,” Jack Brubaker wrote in The Scribbler column in the Jan. 23 Sunday LNP. Brubaker described how Buchanan, despite being regularly ranked at or near the bottom of U.S. presidents by historians, is central to magnificent local tourist attraction Wheatland and has a statue in Buchanan Park. Stevens — whose legacy includes being a fierce opponent of slavery and crusader for public education — has a local statue, too, but it wasn’t erected until 2008. Meanwhile, as Brubaker notes, “builders of the Lancaster County Convention Center destroyed the rear half of U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens’ home and office years ago. LancasterHistory is finally preparing to restore what’s left.”

It’s long past time to give Stevens a bigger spotlight in Lancaster County.

Local history should focus more on “The Old Commoner” and his virtuous deeds than it does on the 15th president — who was, quite frankly, terrible. And we’ll just leave it at that.

We applaud Brubaker’s idea of reviving an old proposal to name the intersection of South Queen and Vine streets in Lancaster city “Stevens Square.” Doing so could be just the start of giving Stevens the long-overdue recognition he deserves.

That intersection is also the location of the future Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Historic Site being developed by LancasterHistory. (Smith managed Stevens’ household and was a successful Black businesswoman in Lancaster.)

When it all comes together, that area of Lancaster city could serve as a springboard for making sure that history-focused tourists leave here impressed by Stevens’ legacy in Pennsylvania and national politics.

We aren’t alone in appreciating Brubaker’s idea. Here’s what some commenters wrote on the LNP | LancasterOnline Facebook page:

— “Old Thad SHOULD be remembered. It is the Old Commoner who best represents the spirit of our county and our Republican party.”

— “We truly need to honor Thaddeus Stevens more. ... It’s past time that this leader for equality and public education be recognized in Lancaster, not just at Stevens College.”

That would be Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology, where the Stevens statue went up in 2008. At least that one did go up.

As Brubaker notes, “Three other initiatives to erect Stevens statues over the years have fizzled.” Among the initiatives that failed was an attempt to erect a statue of Stevens in Harrisburg in the early 20th century.

Given the timing, it’s surprising that the Harrisburg monument was even attempted. The early 20th century was an unfairly tumultuous time for Stevens’ legacy.

Ross Hetrick, president of the Thaddeus Stevens Society in Gettysburg, explained to Brubaker the primary reason that Stevens was not properly memorialized in the United States following his death in 1868.

“(His) enemies — the people who wanted to destroy the country and preserve slavery — were more determined to demonize Stevens as a part of the ‘Lost Cause’ propaganda effort to distort the historic record of the Civil War and Reconstruction,” Hetrick said.

Hollywood didn’t help Stevens’ legacy, either.

The notorious and racist — but wildly popular and influential — 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation” essentially featured Stevens as its antagonist.

We write “essentially,” because the character clearly based on Stevens in D.W. Griffith’s movie is named “Austin Stoneman.”

“Great films need great villains, and other than the nameless black freedmen portrayed in the film, no candidate seemed more outwardly fit to assume the role than Thaddeus Stevens,” historian Josh Zietz wrote in a 2015 article for Politico Magazine titled “How an Infamous Movie Revived the Confederacy.”

In truth, Stevens was a giant in U.S. history. Unfazed by those who sought to demonize him, he not only championed the passage of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery in the United States, but he fought for the passage of the 14th Amendment, which made all persons “born or naturalized in the United States” citizens of this nation and so equal under law.

Now is the time to reinforce Stevens’ true history and legacy. And what better place to do so than Lancaster?

Brubaker believes the time is right, too.

“In recent years, efforts to promote the discredited ‘Lost Cause‘ have faltered as the bitter truth of the terrible toll of slavery and racism has become ever more clear,” he wrote in last Sunday’s column. “At the same time, Stevens’ star is slowly rising as his passionate dedication to equality has become more widely recognized.”

We regularly quote and recognize Stevens in our editorials, because the principles he sought to uphold in the 19th century ring truer than ever today. Two examples:

— Voting to impeach President Andrew Johnson in the U.S. House of Representatives in February 1868, just six months before his own death, Stevens commented on the magnitude of the moment: “We are to protect or to destroy the liberty and happiness of a mighty people, and to take care that they progress in civilization and defend themselves against every kind of tyranny. ... The God of our fathers, who inspired them with the thought of universal freedom, will hold us responsible for the noble institutions which they projected and expected us to carry out.”

— And we wrote in a 2019 editorial that Stevens had little patience for those who, as he put it, are “willing to educate their own children, but not their neighbor’s children.” In an April 1835 speech that saved the Pennsylvania Free Schools Act of 1834 from repeal, Stevens called for “the blessing of education” to be “carried home to the poorest child of the poorest inhabitant of your mountains so that even he may be prepared to act well his part in this land of freemen.”

So let’s push for the creation of Stevens Square. And look forward to the LancasterHistory historic site at that location.

We shouldn’t let those initiatives be the end, either. They should be only the beginning of weaving this great American’s story deeper into the fabric of the Lancaster County he once called home.