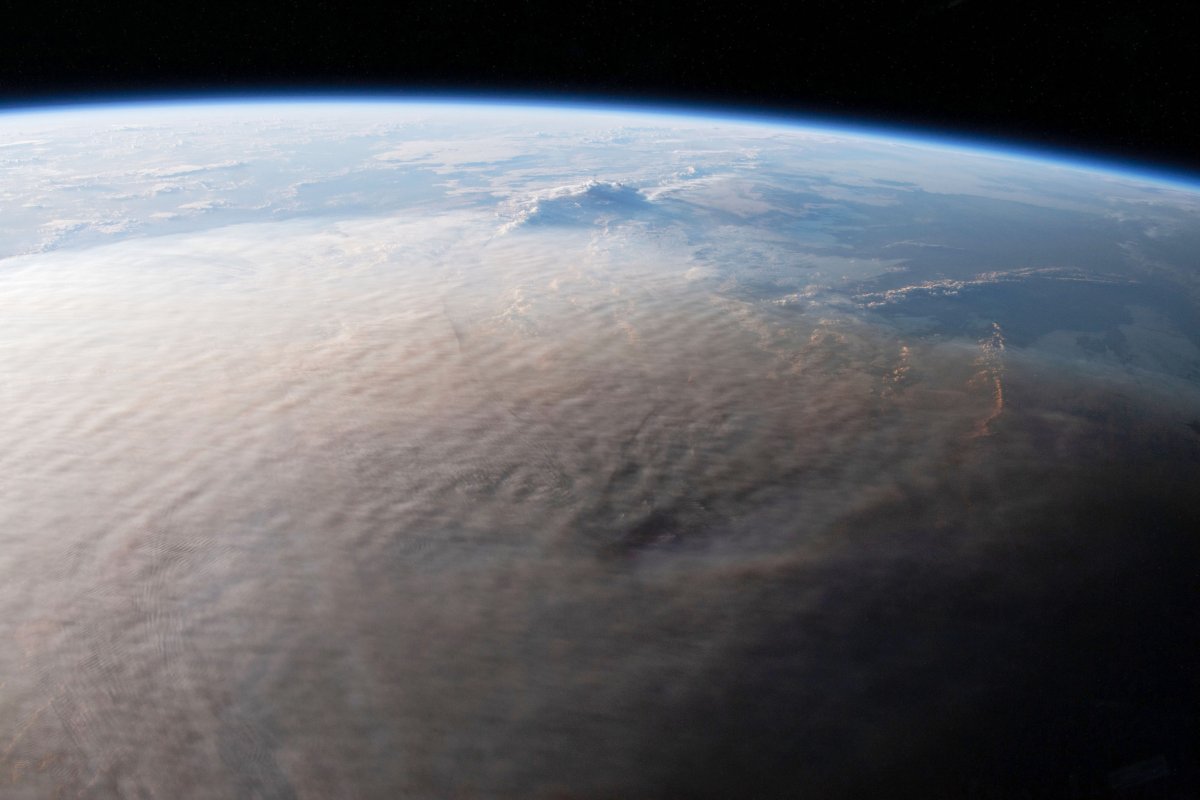

The recent volcanic eruption in Tonga is the biggest on Earth in approximately 30 years and its energy output is comparable to that of Mount St. Helens in 1980.

"What happened here was, a big blob of hot rock came up and got real close to the earth's surface and it weakened the platform of strong rock the island had formed on," Jim Garvin, chief scientist of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and principal investigator of NASA's DAVINCI mission to Venus, told Newsweek.

Garvin said that based on aspects like rock removal and the multiple velocities of the eruption cloud in the atmosphere, the January 15 eruption was equivalent to approximately 4-18 megatons of TNT.

That is comparable to the 24 megatons that exploded at Mount St. Helens, or the 200 megatons of energy that exploded in 1883 at Krakatoa.

Prior to the Tongan blast, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 is the closest equivalent in terms of strength of eruption.

"It's a big, big kinetic energy release," Garvin told Newsweek. "The numbers are in the family of Mount St. Helens, but this is a different type of eruption."

The Tongan eruption also released equivalent mechanical energy comparable to hundreds of Hiroshima bombs, though Garvin pointed out that volcanic eruptions and thermonuclear device explosions have "no comparisons and [are] totally different" from one another due to causes and effects.

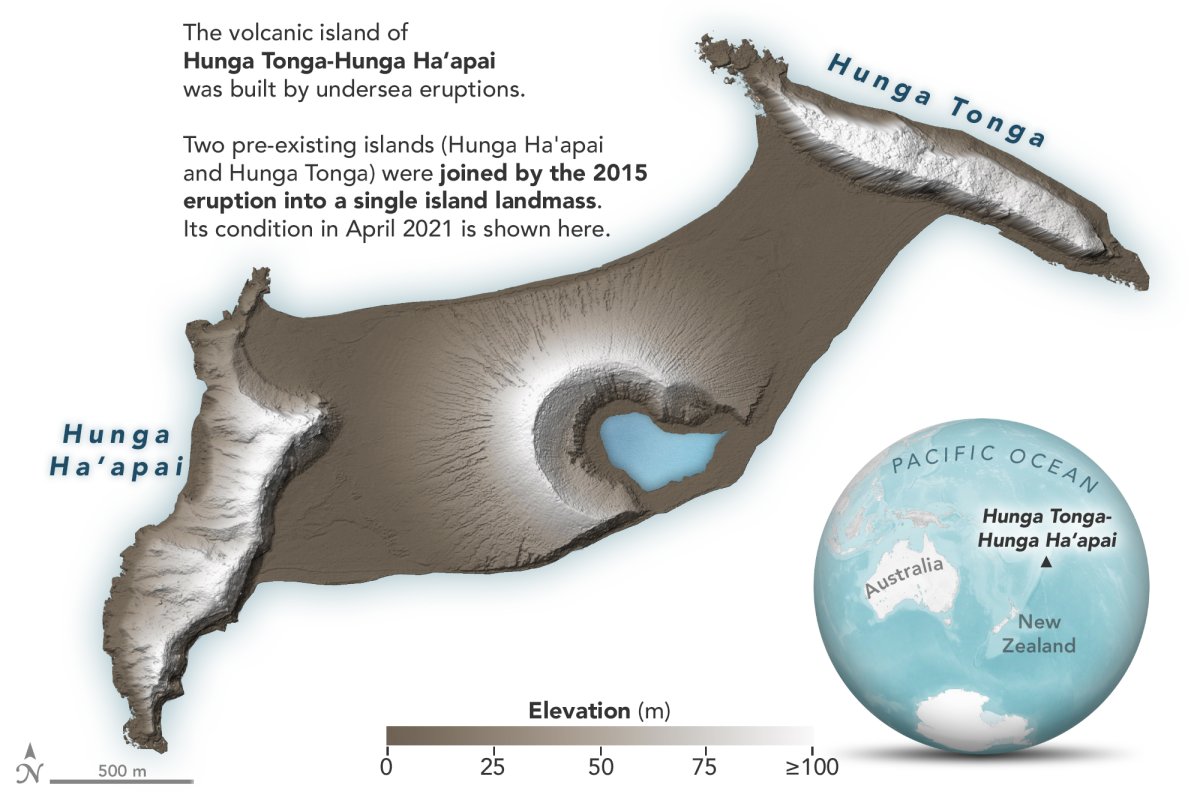

Garvin and other researchers are no strangers to Tonga. They actually had been studying oceanic islands deformed by liquid-rock interactions since 2015, working with colleagues who wrote foundational papers about Tongan volcanoes in the 1970s.

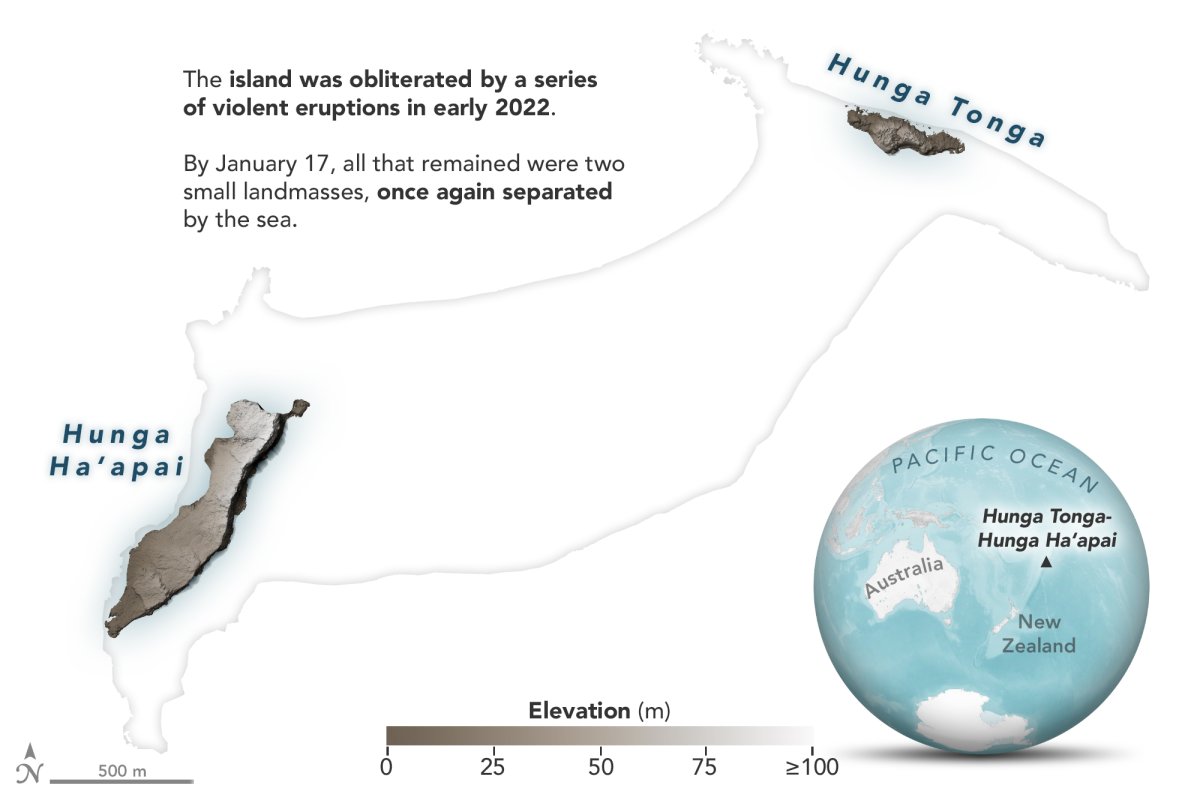

An undersea volcano had been erupting in the South Pacific near Tonga. As Garvin put it, "We saw the emergence of this new type of island" near Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha'apai.

Volcanic eruptions consisting of liquid water and magma combined to produce steam explosions and are known as Surtseyan eruptions.

Garvin said researchers' interest was in the topography of the area, documenting builds and decay and monitoring wave action in the Pacific. He said two massive tropical cyclones directly hit the nearby islands.

About 30 percent of land eroded in the last 6.9 years, he told Newsweek, and just prior to Christmas he and other researchers from the U.S. and Canada "saw a new island grow."

It remains unclear whether the numbers, which remain preliminary, will exceed or fall short of those at Mount St. Helens. Garvin compared the Tongan blast to the small asteroid crater, known as the Meteor Crater or Barringer Crater, in northern Arizona.

The Tongan eruption cloud dissipated rapidly, he added and did not suspend stratosphere dust to affect short-term climate.

"We brought all the investigational tools we had and knew sort of how much stuff there was in the new island that formed in 2015 and reformed in 2021, and now it's all gone," Garvin said. "It takes a big eruption to move that stuff totally nowhere."

The future of Tonga remains uncertain, with Garvin saying satellites, drones and ships being required to understand the crumbling of adjacent islands and to measure what it all means.

"It's going to take a while to build the mass of information to see what the consequences are," he told Newsweek. "I wouldn't be surprised if other less violent eruptions occur."

On the bright side, the research has lent itself to planetary research like on Mars.

There are areas of Mars where satellite imaging shows vast fields of small cones that mimic the Tongan area minus water, Garvin said. Seas, lakes and regional oceans perhaps existed on Mars with enough persistence to create water-rock reactions, and it is possible those areas suggest that maybe volcanic islands erupted underwater and perhaps froze and fossilized.

He said information can be applied moving forward, not only to thousands of earth islands in the Atlantic and Pacific but also on other planets.

"Here, we have sort of a fast-track life cycle of what may have happened on Mars millions of years ago and may have been left as a relic. [W]e need to learn from our own earth to make those decisions," he told Newsweek. "This is another learning experience for us."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nick Mordowanec is a Newsweek reporter based in Michigan. His focus is reporting on Ukraine and Russia, along with social ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.