Beating Shane Mosley – Twice! – Not the defining standard of Vernon Forrest’s too-short life

For many boxers who sweat and bleed and toil to achieve something truly momentous in a sport that frequently can be harsh and unforgiving, what Vernon “The Viper” Forrest accomplished on Jan. 26, 2002, would almost certainly qualify as the high point of their earthly existence. That was the night in the Theater at Madison Square Garden when Forrest, as a 7-1 underdog, knocked down the undefeated “Sugar” Shane Mosley twice to not only wrest the WBC welterweight title from a man then widely considered to be the best pound-for-pound fighter on the planet, but did so in convincing fashion. The unanimous decision for Forrest was free of any hint of controversy, as evidenced by the official scorecards that had him winning by wide 118-108, 117-108 and 115-110 margins.

That signature victory, as well as another in the rematch, earned Forrest recognition as Fighter of the Year from both The Ring and the Boxing Writers Association of America.

Twenty years have passed since the bout that shall forever stand as the apex of Vernon Forrest’s professional life, but time sometimes has a way of shifting public and individual perspectives. What then loomed as the defining landmark of whom and what the Georgian was is more of a footnote now, eclipsed by the circumstances of his violent, tragic and senseless death, at the too-young age of 38. Forrest’s legacy outside of the ring transcends the transitory nature of world titles that can change hands like pots in an all-night poker game.

For many, Destiny’s Child is the name of a former all-girl singing group, since disbanded, but then fronted by now-solo superstar Beyonce Knowles. For a select few, a different Destiny’s Child refers to a philanthropic organization, still in existence in Atlanta, that was co-founded in 1997 by Forrest along with his friend, Toy Johnson, and her mother to aid those most in need of a helping hand.

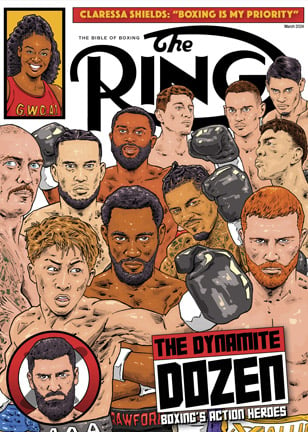

September 2002 cover

Jim Lampley, former blow-by-blow announcer for HBO Sports, agreed with the premise that the true worth of the compassionate Vernon Forrest only tangentially is tied to his status as a two-division world champion whose mostly praiseworthy boxing career was marked by its share of disappointments. What he might have accomplished inside the ropes during another planned comeback ended in a hail of bullets on July 25, 2009, as he attempted to recover cherished personal property that had just been taken in an armed robbery around the corner from an Atlanta gas station/convenience store.

“There are more important things in life than whether you beat Shane Mosley,” Lampley told me when contacted for this story. “Of course, beating Shane Mosley – twice! – was important to him, and rightly so, but he recognized there are things even more important than that. He saw some things that he knew shouldn’t be, and his heart would not allow him to just let it go at that if he could do anything about it.”

It was a surprise of many, but not Pat Burns, a longtime mainstay of the U.S. amateur boxing establishment, when the then-31-year-old Forrest leaned over the ropes after ring announcer Michael Buffer confirmed to the sellout crowd of 5,323 and an HBO viewing audience that what they had just witnessed 20 years ago was indeed real, and yelled to more than a few media skeptics at ringside, “I told ya! I told ya!”

Interviewed afterward, Forrest’s exuberance remained unrestrained. “They say he (Mosley) is the best boxer in the world, the Michael Jordan of boxing,” he said. “I beat him, so does that make me Michael Jordan?”

Count Lampley among those who had not expected Forrest, who had earned a place on the American boxing team which competed in the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, to reprise his conquest of Mosley a decade later. And why shouldn’t Lamps have felt that way? Mosley had come in at 38-0, with 35 knockouts, one of those victories a reputation-embellishing split decision over Oscar De La Hoya (whom he would later defeat a second time). Forrest, although 33-0 with 26 wins inside the distance, was said to not possess the same “wow” factor.

“There was a dinner in Manhattan the night before that fight,” Lampley recalled. “I can’t remember which restaurant, but Lou DiBella may have set up the dinner. One of the guests was Pat Burns (an alternate assistant coach for the ’92 U.S. Olympic team in Barcelona), who was at the Trials when Vernon beat Shane, which was a big shock at the time because a lot of people thought Shane was going to win a gold medal. Because he beat Shane, Vernon went to the Olympics instead.

“It turned out that Pat and I were staying at the same hotel, so we took a cab together after the dinner. I said something during the ride about how Shane was the logical favorite the next night and how he should beat Vernon because of how he had handled De La Hoya. But Pat said, very definitively, `Jim, styles make fights. Never forget that. Shane Mosley will never beat Vernon Forrest. What Vernon did to him in the amateurs, he will do again tomorrow night.’

“It was a perfect call. And then Shane, being the stubborn guy that he was, went right into the rematch with Vernon and got beat again.” (Once more by unanimous decision but by somewhat narrower margins.)

Vernon Forrest hits Shane Mosley with a left hook during their WBC welterweight championship rematch. Photo by Brian Bahr/ Getty Images

After Forrest demonstrated in the rematch that the first victory over Mosley was no fluke, HBO felt comfortable enough with the potential for more such nights that it rewarded Forrest with a six-fight, multimillion-dollar contract. The quiet doer of good deeds with the snapping jab and big overhand right was on the path of the kind of recognition, and major paydays, that presumably separate the indisputably great from the merely good.

It is axiomatic in boxing that to be The Man, you have to beat The Man. But history tells us that is not necessarily so. Mosley – elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2020 — had presumably established himself as a top-shelf attraction by virtue of his conquest of De La Hoya, boxing’s most popular and bankable fighter. But his next three ring appearances, all wins inside the distance, were against competent but non-elite opponents – Antonio Diaz, Shannan Taylor and Adrian Stone. Those triumphs did little to elevate him to the Oscar-sized popularity which he thought should be his by way of natural progression. The two losses to Forrest followed and, although he later reclaimed some momentum with his do-over win over De La Hoya, that success was dialed back a bit by back-to-back defeats to Winky Wright.

There are, of course, varying levels of stardom in boxing as in any sport, but true superstardom is the brightly feathered bird of paradise sought by many, captured by few, and not solely tied to any fighter’s pugilistic talent; there is an X-factor that is liberally splashed with the charisma required to make it all the way to seven-, eight- and even nine-figure emperors’ club. And so it was for Forrest, who came as close as he ever would with the twin points nods over Mosley, only to feel the rebuke of fate when he suffered consecutive losses to chain-smoking, booze-guzzling Nicaraguan Ricardo Mayorga, the WBA titleholder. After the second setback to Mayorga, Forrest took two years off to have two surgeries on his torn left rotator cuff and another on his left elbow to repair torn cartilage and nerve damage. During the interim he revealed that he had been fighting for some time with cortisone shots in those areas to mask the pain of training and then in bouts that counted.

It is a common tale, fighters who must overcome disadvantaged circumstances to achieve things with their fists that others from their hardscrabble neighborhoods can only dream of, and Vernon Forrest’s rise to prominence mirrored that of others who sometimes had to endure fits and stops along the way. The eighth of eight children, young Vernon found a release for any pent-up energy he might have had through boxing, which he took up at the age of nine. The sweet science was good to him, too, as he compiled a 225-16 amateur record. He became the first member of his family to graduate from high school, through the auspices of USA Boxing, which sent him to its training center in Marquette, Mich., where he also took business courses at Northern Michigan University. Things continued to look up with his Trials upset of Mosley, through which he not only earned his ticket to Barcelona, Spain, but also – as The Man who beat The Man – was designated the gold-medal favorite that Sugar Shane had been.

But Forrest’s golden Olympic dream was quickly dashed when, after being stricken with food poisoning prior to his first match, he lost to Great Britain’s Peter Richardson. Not returning from Spain with a medal no doubt cost him a more lucrative promotional deal to turn pro, but he nonetheless put together a string of victories and was 31-0 with 25 KOs when he claimed the vacant IBF welterweight title on a unanimous decision over Guyana’s Raul Frank on May 12, 2001. (Their first meeting ended in a no-contest when Forrest sustained a bad cut in the third round from a head-butt.) But, following a fourth-round knockout of Edgar Ruiz, he was denied the additional prestige of a unification victory over Mosley when the IBF stripped him of its 147-pound title for proceeding with the higher-visibility, higher-paying gig instead of a date with IBF mandatory Michele Piccirillo of Italy.

The losses to the colorful but crude Mayorga did not derail Forrest’s championship aspirations, but they temporarily sidetracked them. “The Viper,” continuing to deal with nagging injuries, rebounded to claim the vacant WBC junior middleweight belt on a unanimous decision over Argentina’s Carlos Baldomir, defended it on an 11th-round stoppage of Piccirillo, and lost it on a majority decision to Sergio Mora. He got it back in on a UD over Mora in the rematch on Sept. 13, 2008.

Photo from The Ring archive

That proved to be Forrest’s final fight, at least in the ring, not that he could have known it then.

“He was ready to come back (after a seven-month layoff) and we were discussing fights for Vernon,” Forrest’s distraught promoter, Gary Shaw, said after being informed of the fighter’s death. “I had told Al Haymon (yes, that Al Haymon; Forrest was the former music promoter’s first boxer) recently I would love to make a fight between Vernon and (then-middleweight champion) Kelly Pavlik. I thought he still had a career in front of him.”

What might have happened had not Forrest pulled into that Atlanta gas station to add air to a low tire on his Jaguar? Or if his 11-year-old godson, who was accompanying him, had not gone into the convenience store to purchase snacks? Would Forrest and the child have continued safely on their way and out of danger? Who can say? What is known is that at 11 p.m. that night, DeMario Ware approached Forrest, gun drawn, demanding that the fighter surrender his Rolex and custom “4X World champion” ring. Forrest gave the jewelry up, but he pulled his own gun and pursued the fleeing Ware, shooting as he ran.

Turning the corner, Forrest lost sight of Ware, but encountered Charman Sinkfield. When he realized that Sinkfield was not the man who robbed him, Forrest turned to return to his car and his godson. That’s when Sinkfield emptied his gun into Forrest’s back before escaping with Ware and their getaway driver, Jaquante Crews. Forrest was later pronounced dead at the scene.

On Oct. 28, 2016, Sinkfield was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. Crews and Ware are serving life sentences. As for the victim of their heinous crime, what Forrest might have gone on to do in the twilight of a borderline-great career can only be a matter of conjecture. He not only hasn’t been inducted into the IBHOF, as is Mosley, he has yet to even appear on the ballot. But there are those who said no shiny ring or plaque hanging on a wall in a museum could ever tell the full story of a good man gone too soon.

Haymon, who never gives interviews anymore and is rarely seen in public, has always had a warm place in his heart for Forrest, his first fighter, and for reasons that do not entirely owe to the skill the Atlanta resident exhibited inside the ropes. Once asked to comment on Forrest’s squeaky-clean demeanor and reputation, Haymon said, “This isn’t a guy who is regularly fingerprinted.”

Not being fingerprinted does not mean Forrest didn’t touch hearts. The non-profit Destiny’s Child, Inc., started in 1997 by Forrest and Johnson, a social worker, came about in part when Forrest witnessed an autistic boy struggling with the seemingly simple task of tying his shoes. After an hour, an empathetic Forrest intervened and tied the boy’s shoes.

“If you sit there and watch a person take about an hour to tie his shoestrings then you realize whatever problems you got ain’t that significant,” Forrest told writer Jimmy Tobin. “A light just went on in my head.”

And Forrest – called “Uncle Vernon” to the emotionally damaged and societally disposable charges entrusted to his care — did not just contribute his money, and a lot of it, to the start-up organization; he contributed his time and friendship. “At first, you think they need you,” told his publicist, Kelly Swanson. “Then you realize you need them more. God has blessed me. It’s the greatest feeling, helping people that other people have given up on.”

They say bad things come in threes, and the death of Vernon Forrest occurred within 30 days of those of Hall of Famer Alexis Arguello, the mayor of Managua, Nicaragua, who reportedly died by his own hand on July 1, 2009, and future Hall of Famer Arturo Gatti, who died under mysterious circumstances on July 11, 2009, at a Brazilian resort.

“I think it’s a little too much for our sport to handle,” Shaw said at the time. “I will say this about Vernon – he was a decent human being. I think people knew how much he cared for kids, underprivileged and mentally challenged people. You can’t afford to lose people like that.”

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.