FEATURE — Driving the stretch of Interstate 15 through Black Ridge is a breeze today. The speed limit is 80 miles an hour on a smooth, paved, two-lane freeway going both directions.

However, for early settlers traversing this same stretch in horse and ox-drawn wagons, the proposition presented a trial of one’s stamina and faith. Those pioneers could not have even dreamed of going 80 miles an hour. They were lucky to go two miles in 60 minutes.

Besides the hot weather, floods and droughts, transportation was one of the most trying aspects of settling the Cotton Mission, or what came to be known as Utah’s Dixie. Some roads could hardly even be considered worthy of that title. They were rough paths through unforgiving terrain.

“The urgent necessity for better means of reaching the outside world was one of the stiffest burdens borne by the early settlers who were already faced with problems of survival that demanded all of their labor and ingenuity,” Karl Larson wrote in his book, “I Was Called to Dixie.” “Road building was one of the most persistent and lasting of the Cotton Mission’s trials … George A. Smith called the route from Harmony to Washington …‘the most desperate piece of road I ever traveled in my life.’”

Instead of the blacktop and gravel roads drivers enjoy today, Smith described the roads as routes covered with stone, volcanic rock, “cobble heads” and deep sand in some places. Larson noted in his writing that roads were built in the line of least resistance, trying to avoid the large rocks, sand and lava ridges.

“During the dry weather the deep sands slowed travelers to a snail’s crawl … Sometimes the road became bottomless mudholes when the red clay was wet and soft. … The sticky viscous mud adhered to wagon wheels (and automobile tires), making travel almost impossible,” Larson explained.

Maintenance along the roads was nothing like today. Mud or dust was the norm. Getting stuck was a regular occurrence in both wagons and early automobiles. In fact, some enterprising locals made extra money by pulling automobiles out of the “mires” in which they were stuck, and it was the most reliable form of transportation at the time, horses, that extracted those early cars.

Another interesting fact about transportation in Washington County is the railroad never reached the county. The closest railhead was in Modena in southwestern Iron County, but Washington County did benefit from commodities shipped via that rail stop. Once it got to that isolated location, though, that cargo had to be transported approximately 70 miles to St. George over a sometimes sketchy road.

“The road from St. George to Modena was very hazardous, with deep sand that turned to sticky mud when it rained,” Lynne Clark wrote in her book “Images of Faith: A Pictorial History of St. George, Utah.” “It was necessary to cross the Santa Clara River several times, never easy, and almost impossible when the water was high.”

Despite all of these transportation challenges, these determined pioneers took a “leap” of faith and persevered, helping Washington County blossom into what it is today.

Peter’s Leap

For the early settlers of Utah’s Dixie, transportation to the area south from Cedar City was a tough proposition. As Douglas Alder and Karl Brooks write in their book “A History of Washington County: From Isolation to Desolation,” once they reached the Black Ridge, it “imposed its terrors.” In the Black Ridge, these early travelers could not follow the stream bed because of large boulders obstructing their path. Instead, they had to drive over lava beds, carving the road as they went.

One particularly tough section they named “Peter’s Leap” after prominent early pioneer Peter Shirts, “who proposed to leap from one lava ledge to another,” Alder and Brooks wrote. Shirts received $300 to construct the route through the Black Ridge. In 1857, these hardy men and women started to use this route, having to ease their wagons down 30% grades by attaching ropes and holding them to brake each wagon’s descent. Other stories indicate some dismantled their wagons to get through the difficult ravine and another is that they lowered wagons down using a cable system.

A better route to replace Peter’s Leap was constructed in 1862, but there is evidence today of three different routes down Ash Creek. The story goes that when they were fashioning a road to replace Peter’s Leap, they moved a boulder and found a dead man under it, which gave it the name Deadman Hollow on later maps.

A Tale of Two Bridges

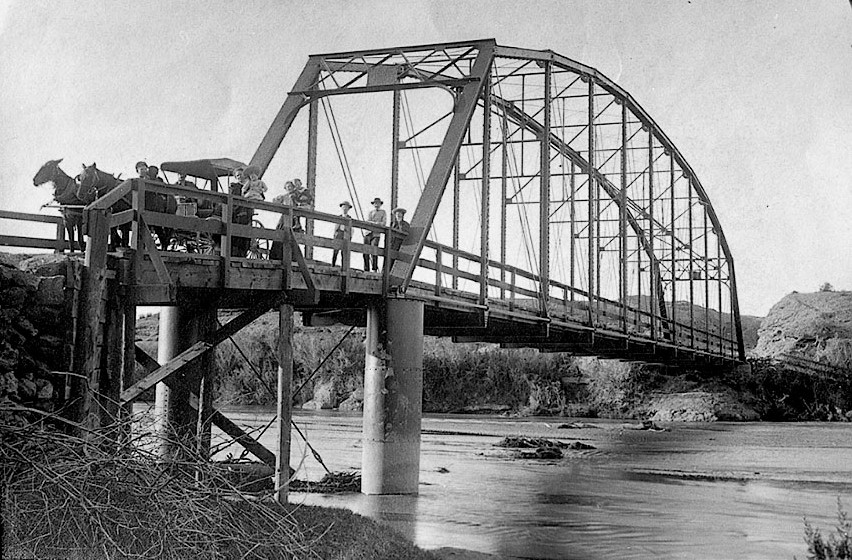

In the early 20th century, Washington County saw the construction of numerous bridges to make traversing the Virgin River much easier for county residents.

Hurricane-LaVerkin Bridge

In 1908, Washington County built a bridge spanning the Virgin River between LaVerkin and Hurricane near what today is called Pah Tempe Hot Springs.

Local residents were elated at knowing the bridge would be built as their trip would not be filled with “awful dread” as the “Washington County News” reported at the time. Before the bridge’s construction, traveling between the two fledgling towns required crossing the LaVerkin Creek stream bed as well as the Virgin River.

The bridge, known as a “Warren pony truss bridge,” spans 75 feet and is supported by concrete-filled steel cylinder piers, according to the Washington County Historical Society.

“Unlike most truss bridges that were built as through-truss types, with struts and braces across the top to connect the top chords, the Hurricane-LaVerkin Bridge is a pony-truss, without top bracing,” the WCHS website explains.

The bridge contributed to the growth of LaVerkin and especially Hurricane, which had only been settled for two years at the time of the bridge’s construction. The bridge became a vital transportation link.

The “Washington County News” gushed over its completion, encouraged people to come and visit it, and foresaw its role in the area’s development.

“When it is finished, watch Hurricane grow,” an April 7, 1908 article in the now-defunct early newspaper boasted. “Come and walk on our steel bridge (the first in the county), bathe in our Sulphur Springs, view our beautiful scenery, walk through our orchards and vineyards. It will do your eyes good, then eat a dish of our strawberries, the best the world produces.”

Even though it no longer serves the main traffic artery since the construction of the Hurricane Bridge in 1937, the bridge continues to function, more than a century after its construction. It is the last remaining Warren truss bridge in the state and was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 1995.

Red River Bridge

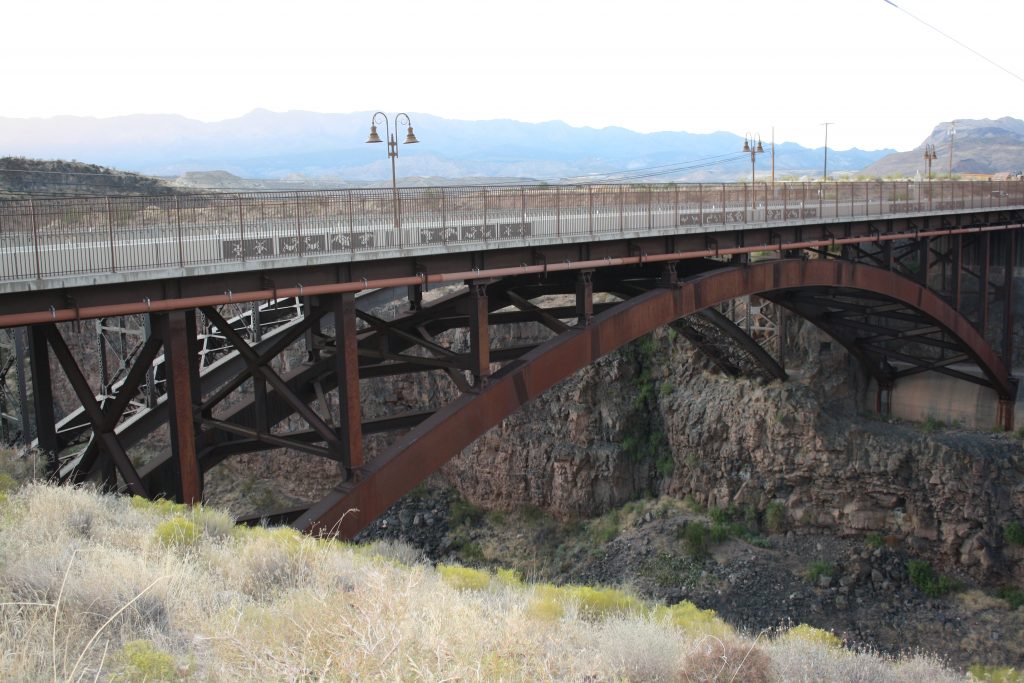

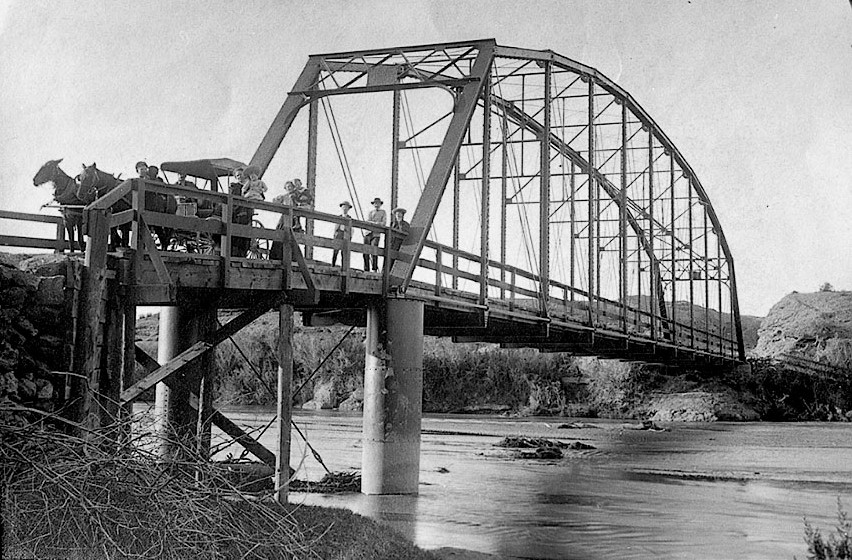

To provide St. George farmers better access to their farmland south of the city, a steel bridge spanning 220 feet was built in 1908. Located on what is now River Road leading into Bloomington Hills, the bridge was painted red and became known as “Red River Bridge,” which some would say is a misnomer because the actual “Red River” forms the border between Oklahoma and Texas.

The bridge was in use until the late 1980s, when the flood that resulted from the Quail Creek Dam failure on Jan. 1, 1989 destroyed it and washed it. A temporary culvert and bridge took its place until the city secured millions of dollars in federal bridge funds to construct the bridge that crosses it today in 1992.

Another flood in January 2005 uncovered pieces of the old Red River Bridge and city officials decided to enlist some local contractors to pull them out.

“In 2013, Eagle Scout candidate Dallin McArthur and his father Dusty along with help from McArthur Welding, untwisted the mangled north bridge entrance, reduced its height by half and restored it back to what it looked like when it was in use,” a plaque by that bridge remnant says.

That north bridge entrance now stands prominently at the northeast end of the current bridge as a sort of museum piece walkers and joggers on the Mayor’s Loop Trail can check out as they pass by.

Arrowhead Trail and the Bigelow Tunnel

In 1916, the main thoroughfare for automobile traffic that linked Salt Lake City and Southern California was designated and became known as “The Arrowhead Trail” after a formation on a mountain near San Bernardino, California that looked like an arrowhead.

Charles Bigelow, a famous race car driver from Los Angeles, promoted the organization of the Arrowhead Trail Association, whose purpose was to advocate for good roads. Bigelow saw huge potential for future automobile development along the corridor and worked untiringly to make it happen. In 1918, Bigelow told the St. George Chamber of Commerce that the city would one day be a key point along the highway.

At the time of Bigelow’s speech, “a rough excuse for a road then passed through St. George, and one car had come through the city that week,” Clarke wrote. “Bigelow assured the Chamber that someday upwards of 100 cars a week would pass through St. George,” which elicited a “hardy laugh” among the disbelieving chamber members.

The road became a boon to the area’s economy, eroding its isolation and bringing with it tourists ready to view the area’s striking scenery, chiefly Zion National Park, which was a major impetus to improving roads to the area. It was even named the “Zion Park Highway” on locally produced maps. At first a dirt and gravel affair, it was finally completely paved by the early 1930s and by then had become known by the name Highway 91 after the U.S. Highway Administration turned to numbered highways in 1926.

Just as with the wagon-driving earlier pioneers, constructing this route required some ingenuity. Old-timers will remember that one of the ways that was accomplished was blasting a tunnel through a hill northeast of St. George to allow Highway 91 to run directly between St. George and Washington. Before the tunnel’s completion, residents had to travel along the base of Foremaster Hill to travel between the two cities.

The tunnel, known as the Bigelow Tunnel and by other names, including “Middleton Tunnel” and “Washington Tunnel” was just less than 500 feet long, 21 feet wide and 13.5 feet high. On the main thoroughfare from the late 1920s to the early 1950s, the tunnel was busy. The WCHS website reports that in 1948, the average hourly traffic was 585 vehicles.

“Sometime before 1954, a cut was made through the mesa and the highway was rerouted along the more level route,” the WCHS website says. “The tunnel was no longer on the main route, but may have still been used as an alternate route for a while.”

The road served by the tunnel was eventually taken out of service. The tunnel still exists today and is located just below the intersection of Middleton and Twin Lakes drives. However, it is on private property and used for storage.

The development of roads such as Highway 91 was key to transforming Utah’s Dixie into a tourist center. Those rude wagon trails are still by and large the main routes followed today, first Highway 91 and eventually I-15.

The completion of state and national highways brought a previously unimagined transformation to Utah’s Dixie and increased the development of restaurants and gas stations, trying to entice visitors passing through to stay the night, starting St. George’s reign as a major tourism center.

I-15

The completion of I-15 through Utah’s Dixie in 1973 truly linked the region to the world. Local leaders knew that deciding where the freeway would be was an important decision and would have a huge impact on the county’s future. County commissioners and St. George Mayor Clinton Snow met with Utah Department of Transportation planners to stress the need for offramps leading to Hurricane, Washington City, and both the north and south entrances to St. George.

Snow lobbied for an offramp that would lead traffic directly onto St. George Boulevard. The route did not alter farmland and bisected the city. Portions of the freeway were elevated on earthen hills, which affected the flow of traffic inside the city. The county’s eastern towns, including Hurricane, LaVerkin and Toquerville were bypassed, as was Santa Clara to the west.

Highway designers decided to avoid going over Utah Hill heading towards Beaver Dam, Arizona, the route of old Highway 91, which was often plagued by snowstorms and was the site of many fatal accidents. Instead, they determined to go to the expense of cutting through the Virgin River Gorge, which proved a boon to the developers of Bloomington but a disappointment to Santa Clara’s roadside fruit stands.

Arizona was at first reluctant to greenlight the construction of the 29-mile portion of freeway between St. George and Littlefield. The state of Arizona didn’t have much motivation to spend its Federal highway funds on an expensive project which would not create anything it could tax, Alder and Brooks wrote.

The 18 miles through the gorge cost $61 million and took 10 years to build, one of the most expensive sections of freeway in the whole nation. To ensure the viability of the project, Utah pledged some its Federal highway funds on the Arizona section, matching Arizona’s appropriations. The joint Arizona-Utah port of entry just south of St. George has helped Arizona collect fees to recover some of its investment.

Local businessmen harbored real anxiety about the freeway coming through, thinking that tourists who previously had to pass through the center of town would now choose not to stop since they would pass through the area at higher speeds. The first few days after the freeway was opened, few people did stop, but soon business picked up. The location of the off-ramps did bring major changes, including the construction of new motels, gas stations and restaurants then shifted to be centered around those freeway exits than where they were previously, in the center of town.

This improved transportation cemented the St. George as a mecca for visitors seeking spectacular scenery and year-round recreation in a mild winter climate. As the title of Alder and Brooks’ book suggests, it has truly come out of isolation and become a sought-after destination for sun-seekers of all ages.

About the series “Days”

“Days” is a series of stories about people and places, industry and history in and surrounding the region of southwestern Utah.

“I write stories to help residents of southwestern Utah enjoy the region’s history as much as its scenery,” St. George News contributor Reuben Wadsworth said.

To keep up on Wadsworth’s adventures, “like” his author Facebook page or follow his Instagram account.

Wadsworth has also released a book compilation of many of the historical features written about Washington County as well as a second volume containing stories about other places in Southern Utah, Northern Arizona and Southern Nevada.

Read more: See all of the features in the “Days” series

Click on photo to enlarge it, then use your left-right arrow keys to cycle through the gallery.

Sign marking Peter's Leap, a difficult place in the Black Ridge for pioneers to traverse in their ox and horse-drawn wagons, near Pintura, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemisch, St. George News

This photo shows the remains of steep switchbacks along the north side of a ravine in Black Ridge known as Peter's Leap to early pioneers, near Pintura, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemisch, St. George News

This photo shows an up-close view of switchbacks along the north side of a ravine in Black Ridge known as Peter's Leap to early pioneers, near Pintura, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of Mike Saemisch, St. George News

This historic photo shows the old Hurricane-LaVerkin truss bridge by Pah Tempe Hot Springs built in 1908, LaVerkin, Utah, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of David Hinton, St. George News

This historic photo shows the old truss bridge and the bridge built in 1937 that made travel easy between Hurricane and LaVerkin, date unspecified | Photo courtesy of David Hinton, St. George News

A car drives along the old truss bridge linking Hurricane and LaVerkin, LaVerkin, Utah, circa 1970s | Photo courtesy of David Hinton, St. George News

The Welcome to LaVerkin sign incorporates the newer 1937 bridge and uses the word bridge metaphorically, calling itself the "Bridge to Zion," LaVerkin, Utah, Sep. 17, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth

The old 1937 bridge sits next to one completed in October 2004 to better accommodate traffic on SR 9 between Hurricane and LaVerkin, Sep. 17, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The old truss bridge as it looks today with a large pipe across it as seen from a viewpoint just below the set of bridges that replaced it, LaVerkin, Utah, Sep. 17, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This historic photo shows people and a wagon and a team of horses on the Red River Bridge soon after its completion, St. George, Utah, 1912 | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

The remains of the north entrance of the Red River Bridge sit next to the bridge that replaced it along River Road in St. George, Utah, May 27, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

The top of the remains of the north entrance of the Red River Bridge, which sits next to the bridge that replaced it along River Road in St. George, Utah, May 27, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

Sign telling the details of the construction of the Red River Bridge in 1908, St. George, Utah, May 27, 2019 | Photo by Reuben Wadsworth, St. George News

This historic photo shows the Bigelow, or Middleton, Tunnel while in use as the main link between Washington and St. George during the heyday of Highway 91, St. George, Utah, circa 1920s or 1930s | Photo courtesy of Washington County Historical Society, St. George News

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @STGnews

Copyright St. George News, SaintGeorgeUtah.com LLC, 2022, all rights reserved.