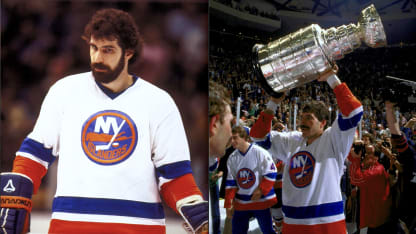

Clark Gillies cheers on the Islanders on June 23, 2021, the last game at the team's Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum.

O'Reilly gained a new insight into Gillies when in 2002 he was named an assistant of the New York Rangers, under coach Bryan Trottier.

"I got to know Clark through Bryan's eyes in New York, hearing many stories about the 1980s Islanders," he said. "I'd always admired and respected Clark, even more so after getting to know him through Bryan."

It was on June 19, 2002, 14 years after his final NHL game, that Gilles was on a flight home to Moose Jaw with his wife, Pam, and their three daughters for the 80th birthday celebration of his mother. He phoned his office during a layover and was told he had an urgent message to call a Toronto number.

"That's when I was told I'd been elected to the Hall of Fame," Gillies recalled during his Hall of Fame induction ceremony. "I sat there and my eyes filled with tears. There was a guy sitting nearby who turned to a friend and said, 'Man, that guy must have had some bad news.'

"Even my wife was concerned until I told her, 'They're tears of joy.' "

Gillies was given a hero's welcome when he touched down in Moose Jaw, larger than life as he had been growing up and as he remains to this day.

O'Reilly remembers a great competitor whom he calls "a reluctant warrior," a player who never gave nor asked for an inch.

"You could just hate Clark, get all psyched up to compete against him," he said. "But when you're sitting there thinking about the game, you're secretly wishing that a guy like that was on your wing instead of opposite you."

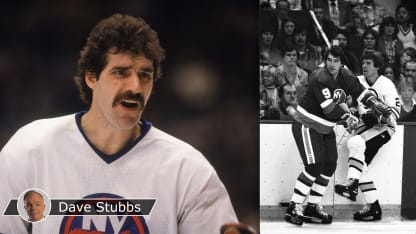

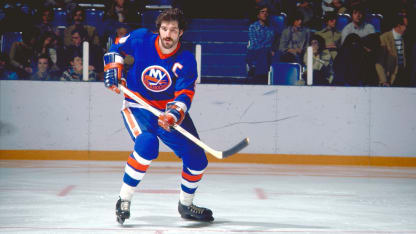

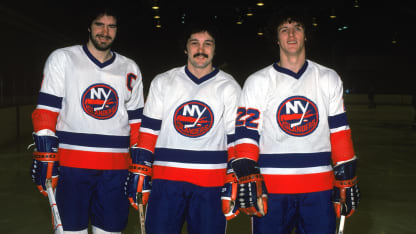

Photos:Lewis Portnoy, Paul Bereswill, Troy Parla, Hockey Hall of Fame; Bruce Bennett, Getty Images