It’s no surprise that La Guerra Civil was chosen as one of the Sundance Film Festival’s opening night premieres. The documentary delivers two of the qualities that make Sundance Sundance: cultural relevance, along with glamorous celebrities to walk the red carpet in Park City, Utah, thanks to director Eva Longoria Bastón and Hall of Fame boxer Oscar De La Hoya.

Except, of course, there was no red carpet. Instead, the Corpus Christi native’s film about De La Hoya’s 1996 fight against Mexican all-time great Julio César Chávez kicked off the festival’s second year as a pandemic-altered, online-only showcase, with the director and the boxer beaming in for a videoconference Q&A. (During the discussion, one of Longoria Bastón’s kids could be heard running through the room and De La Hoya had trouble signing off—Sundance stars on Zoom, they’re just like us!)

De La Hoya and Longoria Bastón are friends, and the Desperate Housewives actress has been producing and directing for both film and television since 2010 (her first feature film, Flamin’ Hot, is also due for release this year). When De La Hoya asked Longoria Bastón if she’d be interested in making a documentary about the fight, she said sure, as long as she could tell the story her way. The hook for the film was meant to be the fight’s twenty-fifth anniversary, which was June 7 of last year (the Los Angeles Times published an oral history by Texas Monthly contributor Roberto José Andrade Franco on that day). But Longoria Bastón was interested in a broader theme, and what the two fighters symbolized, and the result is worth the wait.

“I remember this fight,” she said after the screening. “What’s interesting to me is the cultural divide that that fight had. My household was divided. And so I thought that would be interesting to explore, because I feel like it’s an issue we still face as a community.”

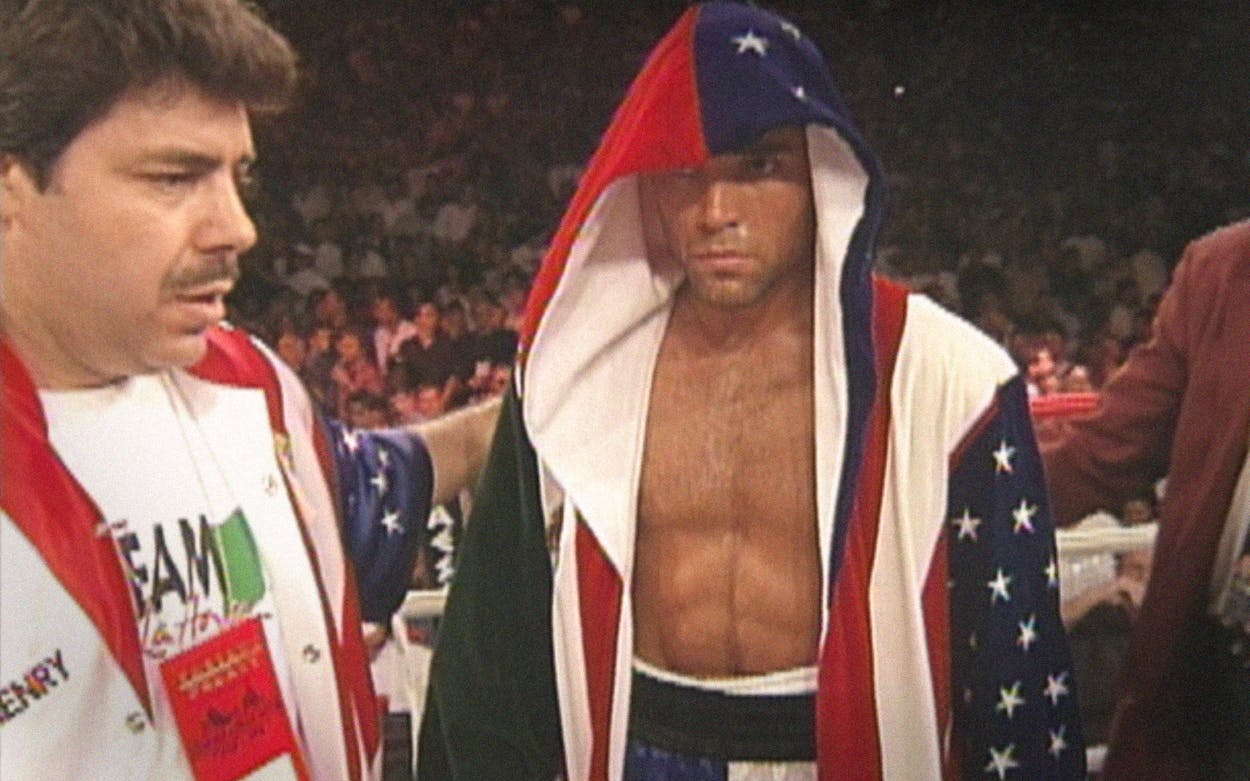

That’s not how De La Hoya saw it. After winning gold at the 1992 Summer Olympics, he took a miniature Mexican flag from his mother and waved it right along with the Stars and Stripes, only to have officials tell him to stop. “So many people remember that moment,” Longoria Bastón said. “Did he know he was doing a political act? No. He was like, ‘I’m proud. This is who I am.’”

And that’s what made De La Hoya so relatable to the director. “I was a huge Oscar De La Hoya fan,” she said. “I grew up with Oscar. I knew him from the Olympics going forward, and I said, oh, that’s me. I saw myself in his identity, as did . . . all my cousins.

“The way we grew up, you know, I’m Mexican American. I’m a Texican. I grew up in a Mexican household, we ate Mexican food, we listen to Mexican music. But if I go to Mexico, you know, I’m the gringa. I’m the American.”

Chávez was revered by Mexican fans both for his seeming invincibility—he won his first 87 fights—and for his willingness to take a beating to get some of those wins. De La Hoya was the younger, more technical fighter, and also—you may have noticed—easy on the eyes. Early in the film, De La Hoya says he viewed the sport as an art form, whereas Chávez treated boxing like a bullfight (later, he says won their bout in part by being like a matador, drawing the more aggressive Chávez to him, and then evading the hard-charging pressure fighter). Along the way, the film touches on great backstory moments like Chávez’s still-controversial last-second knockout of challenger Meldrick Taylor, as well as home movies of a six year-old De La Hoya making his amateur boxing debut.

Despite their stylistic differences, De La Hoya and his family revered Chávez—“Holy s—, I’m fighting my hero . . . what the f—?,” he says at one point in the film. His brother Joel De La Hoya Jr. tells the cameras that even some of their own relatives were pulling for Chávez.

And it’s Chávez who ends up stealing the movie. Longoria Bastón has an almost Barbara Walters–like ability to get the boxer talking, with both speaking in Spanish. He’s blunt about the highs and lows of his career, including his drug use and cartel connections. “I know all the drug traffickers, because I’m from . . . Sinaloa,” Chávez says, referring to the hometown he shares with Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. When Chávez looks back on his losses to De La Hoya (the two met for a rematch in 1998), the proud ex-champ is equal parts gracious and stubborn.

“The first time I met Julio was doing this documentary, and I really fell in love with Julio and his story,” Longoria Bastón said. “He’s so charismatic and he’s so vulnerable and open with his journey.”

While De La Hoya said the spectacle around the fight made it feel like he was having a grown-up quinceañera, he didn’t get to fully feel the love. At a parade to celebrate the win in East L.A., some fans booed—and some even hurled eggs at his float. Both De La Hoya and one of his trainers, Ignacio Beristáin, recall regular taunts of “pocho” (a pejorative for not being Mexican enough) throughout his career. When Longoria Bastón shares that with Chávez, the boxer doesn’t mince words with his disapproval, basically saying that his countrymen who use that word are racist. But he also concedes that he himself couldn’t ever see De La Hoya as “Mexican enough.”

“No. Nunca!” he says in the film, grinning.

Twenty-six years later, the issue still lingers, the emotions still a little raw. “My parents are Mexican,” De La Hoya said in the Q&A. “I was born here in the U.S., very proud. I speak English. I speak Spanish. But it’s like I have no identity. I do not know who I am. I was divided when I fought Julio César Chávez. Am I from the U.S.? Am I from Mexico?”

“People go, ‘Oh, you’re half Mexican, half American,” Longoria Bastón said. “And I’m like, No. I’m one hundred percent Mexican and one hundred percent American at the same time. You don’t have to choose, and you don’t have to assimilate. I grew up in a generation where it was like, ‘Don’t have an accent. Don’t speak Spanish.’ And I think now the tide has turned in that respect. Honor your culture, and hold on to that culture.”

(Another Sundance screening of La Guerra Civil will begin 9 a.m. Central on January 22, with a 24-hour screening window. The film will eventually be released by the sports streaming service DAZN.)

- More About:

- Sports

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- Corpus Christi