Terry Teachout, the longtime Wall Street Journal critic who died suddenly last Thursday at 65, had an easygoing but authoritative style, characteristic of midwestern arts writers for big-city newspapers. He strove mainly to stimulate the interests of the casual aficionado rather than impress other scholars with how much he knew. To meet Terry was to become friends with Terry, and be a beneficiary of his empathy, his wisdom, and his taste.

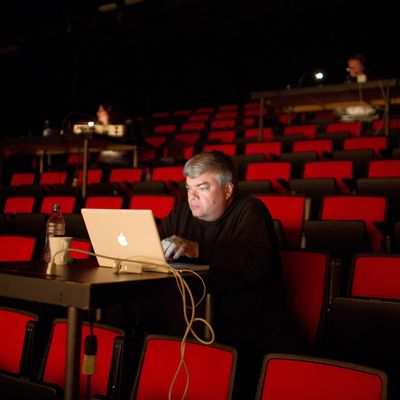

He wrote regularly for the Journal on theater (local as well as New York-based; Terry believed some of the most vital and original work was being done far from Broadway) and on music and other topics for various outlets, including Commentary and his own arts blog, About Last Night (a subtle play on words, so characteristic of Terry; his blog wasn’t just about what happened last night, it was about Terry having been about — as in “out and about” — last night). He was a formidable, prolific, and insightful chronicler of great American artists.

A Missouri native who was a musician as well as a journalist, Terry also published acclaimed biographies (of the choreographer George Balanchine, the columnist H.L. Mencken, and jazz legends Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington); a play about Armstrong, Satchmo at the Waldorf, which was mounted in 2018 at the Alley Theatre; and the libretti for three operas by Paul Moravec, including The Letter (2009), Danse Russe (2011), and The King’s Man (2013), and the cantata Music, Awake! (2016).

I first learned Terry’s name from my grandmother, a concert pianist and teacher who lived in Kansas City, Kansas. She read Terry’s writing in the Kansas City Star, where he’d landed an internship while still in college. After his mentor, the music critic John Haskins, died, Terry replaced him. Although he moved to New York City soon after and stayed there until his death, his experiences writing about local arts led to his expansive and inclusive philosophy about such coverage. Simply put, he believed there was too much focus on New York, to the detriment of arts scenes in smaller cities, suburbs, even tiny towns.

Terry’s attitude toward art coverage carried over into his championing of his colleagues, and of up-and-coming writers who were the equivalent of a small theater company operating out of an abandoned textile mill. (Terry was, after Roger Ebert, probably the single most influential champion of my own writing.) The music writer Marc Myers wrote of how he and Terry used to have jazz-listening sessions at each other’s apartments, and how Terry was responsible for Myers summoning the nerve to leave financial writing to concentrate on his passion. First, Terry pushed him to blog (“You know too much about jazz. You need to write about it.”), then to start contributing to the Journal (“Terry raised an eyebrow, and I said, ‘Fine, done.’”), then to start writing books: “Terry seemed to get a kick out of creating opportunities for me and took great pride in watching me ace them.” After Terry’s death, many of the testimonials were about how helpful he was to others. He seemed to be ego-free when it came to praising fellow writers.

Terry was a prolific and genial presence on Twitter, and we often chatted there about old Hollywood movies, jazz, theater, and other subjects of shared interest. He seemed to be able to get along with pretty much anybody. I DM’d him privately to complain about a particularly belligerent colleague only to find out that Terry considered him a friend. “He can be quite difficult,” he said, “but I’m an oil-on-troubled-water kind of guy.”

I told him that my father was Dave Zoller, a Dallas jazz musician and composer who had formerly been headquartered in Kansas City, and he went on a tear listening to his music and watching videos of him performing. When I mentioned to my father that I had become friends with Terry, he was impressed — possibly more impressed than he’d been by most of my own accomplishments, as he’d been reading Terry’s books and articles for decades, and considered Terry’s Duke Ellington book to be “perhaps the definitive biography of Duke.”

After my father recorded his final album, the as-yet-unreleased Daybreak Express: Music of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, I sent a rough mix to Terry, and he was so effusive that he offered to write the liner notes. “Music has been hard for me since [his late wife] Hilary died [in 2020], but I think this beautiful album is going to help open my ears — and heart — once more,” he wrote to me in late summer of 2020. He added, “I wouldn’t dream of accepting payment.” Terry then went the extra mile and called my father at his home in Dallas and spent an hour talking with him about jazz. He called him a couple more times in the weeks after that. Turns out they knew a lot of the same people from the mid-20th-century Kansas City jazz scene. Dad was over the moon. He told me that becoming friends with Terry, a writer he’d admired for so long, was the second best thing to happen to him professionally during the final year of his life, after recording his Ellington album.

Terry believed you could find good art almost anywhere, and that you would be more likely to believe this if more big-city journalists would make a commitment to leave their regional comfort zones and seek it out. In my conversations with him, he sometimes referred to this philosophy as “truffle-hunting,” because “you’re not going to experience a lot of the good stuff if you wait for a PR person to tell you about it. You need to go out in the forest and find it.”

He elaborated on the idea in 2019 to the Kansas City public-radio affiliate KCUR. “Theater is an activity that people do on the highest level of seriousness and attainment throughout the country. It’s not like it was 50 years ago, when most of the serious theater in a town the size of Kansas City would be touring companies. No, it happens here, it’s made here.” His final review, published January 6 in the Journal, was of The Streets of New York, mounted at one of his favorite small venues, the Irish Repertory Theatre.

Terry died a little more than a year after the death of Hilary, at the home of his new girlfriend, Cheril Mulligan. He and I had been corresponding regularly via Twitter DMs about our wives’ health problems. Hilary had been dealing with respiratory problems for over a decade. She had a lung transplant in 2019, but died in 2020, the same year that my wife, Nancy, died of the metastatic breast cancer she’d been coping with for two years.

Four weeks later after Hilary’s death, he wrote me, “All I can tell you is this: After a month, it’s a TINY bit easier — not that it doesn’t hurt every single minute, but I’m just now starting to imagine the possibility of the possibility of coming to grips with the loss, if you see what I mean.” That’s what the many people Terry influenced, inspired, and loved will experience at some future point: the possibility of the possibility of coming to grips with losing him. But not today.