In the long, hot summer of 1976, Pink Floyd were holed up in their brand new studio in Islington making what would become their 10th studio album, Animals. Ten years earlier, they had been the sound of the underground and soon began making their name on the London scene. Thanks to 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, Pink Floyd had become the biggest underground band in the world. And, now, as the establishment themselves, they were old news.

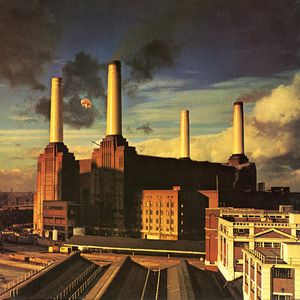

Britain was in the grip of industrial unrest and a drought that seemed to provide a metaphor for the lack of direction in the country. Far-right groups were stirring, punk rock was emanating from the children of those who’d welcomed Floyd a decade earlier. With one eye looking over his shoulder, Roger Waters wrote a Pink Floyd album that remains discrete within their catalogue even today. Released at a time when anything more than a three-minute, three-chord thrash was an early candidate for cancel culture, Animals stands as odd and as proud as those four thrusting chimneys on the cover.

Even today, for an album with such a well-known, iconic sleeve, comparatively few know the music within. Given that the group had already attained megastar status: it was a difficult album to promote, aside from the fact it was by Pink Floyd and they promoted themselves. With three pieces all over 10 minutes long, there was no track to take to radio. Even in the US, where singles had repeatedly been taken from albums, they knew the game was up, and had nothing to offer. Just how did a group that had the world at its feet come to make quite such a bitter, idiosyncratic record?

The roots of Animals lay in Pink Floyd’s 1974 British Winter Tour. It was here that the band debuted the two grim, lengthy songs they’d rehearsed in that windowless room next to the Wimpy Bar in King’s Cross earlier that year, that sat with their other newie, then known simply as Shine On. Whereas Shine On seemed warm and poetic, You Gotta Be Crazy and Raving And Drooling bordered on the atonal. The former had the lyrics: ‘Gotta keep all of us docile and fit, gotta keep everyone buying this shit’, while the latter stated: ‘How does it feel to be empty and angry and spaced, split up the middle between the illusion of safety in numbers and the fist in your face?’ Their sole purpose seemed to be to harsh their audience’s mellow.

Nick Sedgwick, Roger Waters’ friend who toured with the group in the early 70s and wrote the memoir In The Pink, captures the London in which the Floyd were rehearsing. It was a time of unemployment, inflation, and IRA bombings. Britain, not for the first time, nor the last, appeared to be going to hell in a handcart. “Everywhere was grey, sodden, and above all else, cold,” he wrote. “A kind of gloom set in: a languorous melancholy, which seemed exactly commensurate with the prevailing rhythm of the national psyche.”

The mood of despondency in Pink Floyd was exacerbated by the regional tour that followed. The band visited Stoke-On-Trent’s crumbling pleasure palace, Trentham Gardens, on a Tuesday night in November 1974. “What the fuck are we doing playing in a building like this?” Waters said on seeing the hall. “We really should stay in one place. It would be more expensive for the kids, what with train fares and the rest, but we’d do much better gigs.”

The dissatisfaction, that is commonly seen as setting in three years later, was already taking hold. Sedgwick captures the creeping malaise perfectly: “I watch Dark Side Of The Moon from the stage, though off to the side and from the audience… Amazingly, one of the crew is asleep on a pile of cables. Hard to credit what with the noise and the heat, and the girls urging the crowd to clap along, and Dick Parry busting a gut in Money and the boys so close you can see the beads of sweat burst from their brows. But you can even grow used to magic when there is enough of it.” By now, the Floyd had grown used to everything. And this was the root of Animals.

After the recording and touring of Wish You Were Here, 1976 marked a fresh start for the band – they had bought a property in Britannia Row, Islington, the previous year. The old Architectural Abdabs themselves, Waters and Nick Mason, brought in architect Jon Corpe, their old friend from Regent Poly, to help them realise their dream of a purpose-built studio and, after some recordings by Robert Wyatt and Michael Mantler, Pink Floyd were ready to begin work. Brian Humphries was employed by the group as their full-time engineer at the studio. He had first worked with them on More, and become their front of house sound man from the Wembley shows in 1974. He had also engineered Wish You Were Here.

“I went and looked at it, but I did feel a bit ‘Do they know what they are getting into?’” Humphries says. “They had got a friend of theirs who was an architect. I think he was bluffing his way through it because I don’t think he knew anything about soundproofing, so I kept away. When they had finished touring, they all went on holiday, so of course I had to keep Britannia Row running because I was the only engineer there at the time.”

Recording began in April 1976, just as Harold Wilson resigned as UK Prime Minister, ushering in the ‘Sunny Jim’ Callaghan era. Although it’s far too reductive to suggest that it was solely an era of industrial unrest, football violence, bovver boots and the National Front were all contributing to a sense of unease. A flirtation with Nazism was borne out by punks adopting the swastika, and the gesture David Bowie appeared to be making to fans as he arrived at Victoria Station that May seemed to give credence to a new right within popular music. This was coupled with the rise of the Sex Pistols, whose lead singer Johnny Rotten was first spotted wearing a T-shirt with 'I Hate’ written above a Pink Floyd logo T-shirt, complete with their eyes gouged out.

“Wish You Were Here was everywhere in 1975 and early 1976: it’s great but bloody hell, it’s turgid. Funereal,” England’s Dreaming author Jon Savage says. “As for Johnny, Yes and ELP were more annoying in 1976 – if you even thought about them – but there’s the rub: Pink Floyd were still an issue. I bet you Lydon had listened to them avidly before his Damascene conversion.”

It was time to lick the slumbering numbers into shape, and by adding a new song, Roger Waters loosely based the concept for Pink Floyd’s album on Animal Farm, George Orwell’s 1945 satire on Stalinism that equated social classes with animals. “The species are read as representing the various levels of capitalist society on the cusp of Thatcher’s neoliberalist reforms,” Erwin Montgomery and Rob Horning wrote in The New Inquiry. “The pigs are the aloof elites; the dogs the servile, manipulative managerial class; and the sheep are the working masses from which the dogs extract value.”

You Gotta Be Crazy was changed to Dogs, with better lyrics; Raving And Drooling became Sheep. The group worked from April to December. “All four of them would lay down the basic tracks,” Humphries recalls. “It was basically more Roger, because upstairs they had a gaming room with a billiard table.”

Dogs – the only album co-write with David Gilmour – takes up the first side, and is one of the group’s greatest performances. Gilmour’s playing is unparalleled as he romps through a range of solos and refrains. It’s almost as if Dogs shapeshifts every single time you hear it. After eight minutes, it fades away, Echoes-like, to a brooding instrumental section. But here, there are no spacey gulls, just barking, baying animals, complete with Humphries’ performing as well.

“I was doing the dog whistling,” he laughs. “I used to bring Tina, my Golden Retriever into the studio with me, when it was overdubbing time and it wouldn’t be that crowded.”

The way the barking dog becomes a vocoder during this section shows a band able to play around in the studio to come up with something unique. “That was Roger on the mixing console. Even back to the days of More, the band liked to be involved in the mixing.”

The song illustrates the dog eat dog world. Gilmour’s vocal lines in the first half encapsulate, the ‘real need’ to succeed, the desire to get on. When Waters appears, he realises the possibility that, as the titular dog, he has been used. But it’s too late – drowning not waving, as the stone takes him down, he reflects on his life; real power, like the soon-to-be-decommissioned power station on the album’s cover, appeared to be there, but has ultimately alluded him.

“Roger and Nick wanted to listen to the 24-tracks,” Humphries recalls. “In Dogs, there are some very heavy-duty drum things in the middle eight; that wasn’t Nick, that was David. That’s not a well-known fact. They asked me if I could find sound effects of dogs and sheep. I was letting them get on with the 24-tracks. Unbeknown to me, they wiped David’s over-dubbed drums. I got hell to pay for that. It wasn’t my fault; I was being asked to do something else, they were in control of the 24-track and the remote. So, David had to redo the drums: he wasn’t a happy bunny.”

Pigs (Three Different Ones) is arguably the album’s most difficult listen, one of Water’s grimly groovy three-chord tricks, looking at three establishment types: the ‘dragged down by the stone’ businessman from Dogs reappears; a ‘ratbag’ that Waters had spotted at a bus stop near Britannia Row, who may or may not be Margaret Thatcher, the then-leader of the Conservative Party; and finally, moral watchdog Mary Whitehouse, the head of the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association.

The music is a queasy funk: and the voice box used by Gilmour – a device so giddily paraded by Peter Frampton a year earlier, all shiny backlit locks – here was being used to make quite the most horrible noise you could possibly imagine. Of course, the choice of Mary Whitehouse as a target specifically railing against falling values in the UK was apposite – but the White House was also the building that had housed a leader as corrupt as Richard Nixon, who had been impeached two years earlier.

The former Raving And Drooling, recast as Sheep, is a fitting climax to the album. The sheep believe they are ‘harmlessly passing your time in the grassland away’, before realising things may not be as they seem. At the song’s heart, there is a rewritten Psalm 23, run through a vocoder, intoned by Nick Mason. ‘With bright knives he releaseth my soul, he maketh me to hang on hooks in high places, he converteth me to lamb cutlets.’ The sheep had better mobilise.

“I don’t think the humour of the work has ever really escaped in the way it might have,” Waters told Chris Salewicz in 1987. “The political subject matter on top of it has been generally dour. I suppose I have always appeared as a rather melancholy person. But I’m not. My situation is like the opposite of the cliché of the comedian who when he’s not performing is a miserable sod.”

The sheep finally rise up against the dogs: ‘Wave upon wave of demented avengers/March cheerfully out of obscurity into the dream.’ Mobilised to do something, they’re ultimately crushed by the next wave of Pigs served by Dogs. History repeats itself. Gilmour’s good rockin’ solo at the very end is like an enormous, joyous release. It’s the only time you feel anywhere near becalmed during the album’s three lengthy pieces.

Animals is often cited as the beginning of the schism between Rick Wright and Roger Waters. “Animals was certainly mostly Roger’s ideas, and Dave wrote the music for Dogs,” Wright told Karl Dallas in 1978 in Melody Maker. “I, in fact, didn’t contribute anything, and that was partly because there was enough material from Roger and also because I wasn’t feeling very creative anyway.”

“There was always the thing about Rick,” Humphries adds. “It’s been in print – Roger said he never pulled his weight; he never did anything. If you listen to the beginning of Sheep, that Fender Rhodes solo, that was just me and him in the studio. The lights went down, I did it on purpose, I said to him: ‘Rick, just do your thing.’ We had about four takes, and we used the first one that I told him was great. When I listen to the album today, I think back to that day and Rick. He was quiet – he put his four penn’orth in when needed, but I think Nick and Roger had already made their mind up, that he wasn’t going to be around for the next album as such.”

If Wish You Were Here had been a rumination on Water’s failing relationship with Judith Trim, then Animals was a celebration of his new marriage to Carolyne Christie. Well, at least two and a half minutes of it. Pigs On The Wing (a pun on the phrase pigs might fly) bookends the album, offering a glimpse of sanity and love in the troubled world. If they didn’t care for each other, they, too, would be ground down in the end.

A fter the acres of publicity about the escaped inflatable pig, expectations were high. With a launch at Battersea Power Station’s social club on January 19, the album was released in the UK two days later. Even those who were involved in the long-awaited project were wrong-footed.

“I was a big fan of theirs before I started doing photography for them and Animals is one of my least favourite,” pig-snapper Howard Bartrop said. “I was disappointed it didn’t sound like The Dark Side Of The Moon.”

He wasn’t alone in that view: “The nihilism of Animals is overpowering. We are all dogs, pigs or sheep, and none of us can do any more than make a pretence of being a higher species,” Bart Mills wrote in the Daily Mail. It was Melody Maker’s review that had the greatest resonance – Karl Dallas wrote that it was an “uncomfortable taste of reality in a medium that has become, in recent years, increasingly soporific.” – but it was the headline of the feature that many recall: Punk Floyd. Mick Farren wrote in NME: “There are enough things to be depressed about. I know the dogs eat the sheep. I can do without exquisitely crafted reminders.”

Some critics didn’t even bother: “I didn’t even listen to Animals when I was sent one on its release,” Jon Savage says. “Still haven’t, even though I still have it somewhere. I put this to Roger Waters in the mid-80s, when I interviewed him around the release of [his 1987 solo album] Radio KAOS: I was a huge Pink Floyd fan up to and including Wish You Were Here but that was it after then.’ ‘I can understand that,’ he replied. He was very nice about it, actually, and gave me a great story about a dream involving Syd Barrett.”

However, Brian Humphries has fond memories: “It showed the heavy metal in the band. I have listened to the album a few times since and been pleasantly surprised.”

“I suppose I always saw Animals as more of a punk album,” Nick Mason said in 2019. Not long after its release, Mason would be producing The Damned at Britannia Row.

As the years pass, Animals gains greater relevance. And it was little wonder that the Animal Farm narrative was seized upon by Waters for his Us + Them tour, railing fully at Donald Trump, the ultimate Dog in Pig’s clothing. “We don’t rebel against Trump, we elect him,” Waters said in 2020 – the ultimate act for Sheep to do. In 2017, New World Design architect Jeffrey Roberts proposed four golden flying pigs directly in front of the Trump Tower in Chicago; inspired directly by Animals, and also by the fact that Trump had recently called a former Miss Universe ‘Miss Piggy’.

The figures depicted by the album are seen daily in modern life: Dogs, Pigs and Sheep move among us. As Orwell wrote, “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and man to pig, and from pig to man again: but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

“I can’t write a song that isn’t connected with how I feel,” Waters said in 2018. “I think that maybe if my songs have an enduring quality to them, it’s that they’re truthful, that they’re very heartfelt. I mean, I’m not saying I know the truth and other people don’t, but I’m saying I tell the truth I believe in as directly as I can in the songs I write.”

Animals sits, edgy, provocative, out there on the outer fringes of ‘good taste’. A reflection, albeit from that of a very wealthy socialist, of a Britain, riven by industrial disputes; grimy, future Yewtree celebrities ruling the roost. The album offers a stunning honesty, a taste of the nation. It was the first that the group were to tour to explicitly promote, and by the time of its release, the band, with Snowy White on guitar and Dick Parry on sax, were out on the road in Europe. When the tour reached North America, and the band and their inflatable menagerie played in stadiums, matters took a darker turn.

“Rock’n’roll in stadiums is genuinely awful,” Waters was to reflect a decade and a half later to Q Magazine. “These concerts are just like Tupperware parties – held in honour of the Great God Tupper – with 50,000 people, only they don’t buy Tupperware, they buy hot dogs and T-shirts and occasionally look up to watch those disgusting video screens that are all out of sync and make you feel sick and torture you.”

Well, what on earth could go possibly wrong?