A peaceful protest was held on Jan. 13 against the cutting of pine and hardwood trees at Housatonic Meadow State Park in Sharon.

Photo by Lans Christensen

SHARON — In the end, they were not able to overcome the might of the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) and its fleet of mighty rolling steel. The 66 pine trees that DEEP had determined were a safety hazard were cut down on Thursday, Jan. 13, at Housatonic Meadows State Park, just off Route 7 near Route 4 in Sharon.

As the powerful timber cutters did their work, about 30 protesters stood politely behind the barriers that had been set up to keep them away from the workmen. They held hand-lettered signs on old bits of cardboard, saying, “DEEP shame” and “Homewrecker.”

The fight over the fate of these pine trees (and several hardwood trees) has been going on since December, when a DEEP crew took down about 70 trees, including a stand of oak trees, at Housatonic Meadows State Park.

A number of area residents who take walks there noticed the limbs and tree stumps and immediately began an email campaign that included entreaties to state Rep. Maria Horn (D-64) and Sen. Craig Miner (R-30) to intervene; see story this page by Patrick L. Sullivan.

The state responded to the outcry by offering a meeting on Zoom on Jan. 6 in which DEEP Deputy Commissioner Mason Trumble tried to explain why the trees had been removed and why there were plans to remove another five dozen or more.

The youthful, bearded Trumble introduced himself as a former river guide, a hiker and a fly-fisherman. He promised the 90 viewers who had signed in to the Zoom that a full hour of the presentation had been set aside for public comment.

He and other DEEP staffers then explained in detail why the decision had been made to remove what adds up to about 100 trees from the state park, which is a popular site for day visitors and for campers.

The graphics from their presentation, showing the number of trees removed after the Jan. 6 meeting, can be seen on Page A6.

Who uses the park

After the meeting, Will Healey in the communications department for DEEP responded to questions from this newspaper about the park.

Healey noted that use of all outdoor recreational areas in Connecticut has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as people seek a safe way to get out of the house.

That explains in part a large increase in daytime use of Housatonic Meadows State Park. Because of park closures that significantly throw off the numbers, 2020 statistics are not included.

• In 2019, there were 28,727 daytime-only visitors

• In 2021, between January and October there were 41,300 daytime-only visitors (statistics are not yet available for November and December)

There has been a decrease in overnight camping, in part because the campsites have been closed at times because of COVID concerns.

• In 2019, there were 3,250 campsites reserved

• In 2021, there were 2,899 campsites reserved

Housatonic Meadows, which became a state park in 1927, is on 452 acres right on the shores of the Housatonic River, with a 2-mile stretch of the river dedicated to fly-fishing. There are 61 campsites, a parking area and several picnic tables there.

Although no one has done a census of the number of trees in the park, Healey said it is estimated that there are more than a thousand trees in the day-use area of the park and another 1,000 trees in the camping section of the park.

A matter of interpretation: Trees

In this dispute over the fate of the trees, nearly every person involved has a different interpretation of what matters most.

One opinion is that of the DEEP staffers who made the initial decision to have the trees removed.

The state began a “hazard tree removal” project in 2018. Trees have a lifespan and eventually begin to fail and then fall. Even mighty oak trees eventually begin to age out. Adding to the stress on trees is the unpredictable weather and periods of drought and late frosts.

Also extremely damaging, according to the DEEP experts in their Jan. 6 Zoom presentation, is predation by invasive insects, which has been extensive in recent years.

Many ash trees died last year after they were attacked by the emerald ash borer; and many oaks were attacked by the caterpillar for what had been called the gypsy moth; that name is now being changed because it is considered derogatory to an ethnic group.

Trees often fall in the woods, and that is just part of the natural cycle. But when trees fall in a place that humans use, and which is managed by the state, steps are taken to remove potentially hazardous trees.

The DEEP staff said in their Zoom presentation that trees have fallen at several state parks in the area; there have been fatalities and there are now lawsuits pending against the state for negligence.

At Housatonic Meadows, a tree fell across the parking lot in 2021.

No one was hurt.

But DEEP foresters then went in to the park and examined the trees there to determine which might conceivably fail and present a hazard to humans using the park. About 150 trees were selected and removed, in the December culling and a subsequent culling on Jan. 13.

A matter of interpretation: Moratorium

One topic that has been disputed is whether DEEP promised during the Jan. 6 hearing to stop cutting trees.

Several of the protesters included in a long email list discussing the tree removal were certain that the state had said it would stop cutting trees for the moment.

Most of the people on the email stream confirmed instead that DEEP Deputy Commissioner Trumble had apologized for not communicating to the public the plan for the tree cutting, and had promised to be better at communicating in the future. But he did not promise a moratorium on tree cutting.

By Jan. 7, the email group took note that the parking lot at Housatonic Meadows had been plowed, and this was seen as evidence that a tree cutting was imminent.

Several members of the group suggested that they meet at the park and have a peaceful protest in an attempt to stop the cutting. All potential participants were warned that they might end up being arrested.

The protest came together on Thursday, Jan. 13. About 30 people turned out with signs protesting the cutting. No state police troopers were there, but the workmen were protected by temporary barriers and the presence of Environmental Conservation police.

A matter of interpretation: Wildlife

Before the Jan. 13 protest, the pro-tree life group began to realize that the tree cutting would continue as planned; they sought solutions that might delay or stop the cutting.

Several people suggested that there might be an animal on the federal endangered list that could be spotted at the campsite, and that the site could be declared a habitat that should not be disturbed. Suggested animals included the slimy northern salamander, the Eastern cottontail rabbit, and the bald eagles that live in several spots along the river.

Funds were collected for possible legal action demanding that the state perform a survey of endangered species in the area. An attorney was consulted but said he would not take on the case.

While there is no question that this stretch of the river has eagles (including several that came out on the day of the protest), their presence was not enough to stop the cutting.

A matter of interpretation: Trees II

As for tree health, there was disagreement even among members of the protest group on what conditions should spark an intervention.

The DEEP staffers in their Jan. 6 Zoom talk were very clear about why they considered the marked trees as a hazard. They talked about general aging, and about the damage caused by the emerald ash borer and the caterpillar for what was formerly known as the gypsy moth.

There was a huge infestation of the caterpillars last summer; new egg masses are already in evidence that show this year’s infestation will be even worse, with as many as 100 caterpillars hatching from each egg mass. Trees can recover from one year of infestation, the DEEP staff said, but each year of attack weakens them.

While some of the protesters acknowledged the damage caused to area trees by the emerald ash borer and the caterpillars, others insisted that no one should assume a tree is going to die until its death is imminent. No tree should be cut down before its time; it would be preferable to go through and do a thorough pruning of the endangered trees and see if they can pull through. Taking two sides in this debate were two local arborists, one a resident of Sharon and the other a resident and longtime town tree warden from Cornwall.

In the debate over whether the trees should be removed, one well-known and respected environmentalist in the region said that, in his opinion, foresters should not be allowed to decide on the fate of trees because they make their decisions based on the sale of trees to loggers.

He said that only arborists should be allowed to decide which trees are healthy.

A matter of interpretation: Humans

The same environmentalist who had said foresters primarily care about logging the trees and selling the timber had also suggested that the state simply move the picnic tables away from the trees if the main concern was the safety of humans using the park.

When that question was presented to Will Healey in the DEEP Communications Office, he responded that, “The picnic tables are only one of the potential targets in the area of the undermined trees that were removed at the top of the slope.

“Those trees also threatened the parking lot, as evidenced by the tree that fell into the parking lot in 2021.

“Also, simply removing the picnic tables would not stop the public from congregating along the top of the slope to enjoy that area with a view of the river.”

It can’t be determined ahead of time how people would respond if the picnic tables were moved or removed. However, an ongoing challenge for residents of area towns in recent years has been unsafe use of the Housatonic River. There have been several drownings in recent years in the river, especially near the fast-moving but apparently placid waterfalls in Kent and Falls Village/Salisbury.

Several people have also queried the decision by DEEP foresters to cut down the trees. Who will get the windfall from the treefall, they have asked.

Healey responded that, “Hazard tree removals are a cost to the state and taxpayers, not a revenue source.

“The contractor was awarded the work based on their lowest bid response to DEEP’s detailed scope of work. Initially all logs and branches resulting from the tree removal/pruning effort were to be chipped. We have since changed the scope of work to include hauling those logs that are suitable for lumber to our DEEP Sawmill. The resulting lumber from these logs hauled to the Sawmill will be used for picnic table stock or other state park uses. The contractor is not selling or using the chips or logs for their own gain.”

If anyone would like to watch the recording of the Jan. 6 meeting or read the transcript, they can be found online at https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/State-Parks/Parks/Housatonic-Meadows-State-Park/.

Graphics Courtesy CT DEEP

Graphics Courtesy CT DEEP

Author Anne Lamott

On Tuesday, April 9, The Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie was the setting for a talk between Elizabeth Lesser and Anne Lamott, with the focus on Lamott’s newest book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love.”

A best-selling novelist, Lamott shared her thoughts about the book, about life’s learning experiences, as well as laughs with the audience. Lesser, an author and co-founder of the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, interviewed Lamott in a conversation-like setting that allowed watchers to feel as if they were chatting with her over a coffee table.

“I feel like I’m in my living room talking with my closest friends,” Lamott said.

In her 20th book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love,” she goes back in time, writing about her own personal life experiences in a candid way, about her family, recovery and her faith. Lamott relates coming face to face with intense emotions and multiple epiphanies and lessons she’s learned.

The book explores the transformative power that love has in our lives: how it surprises us, forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, reminds us of our humanity, and guides us forward.

“Love just won’t be pinned down,” she says. “It is in our very atmosphere and lies at the heart of who we are."

“We are creatures of love,” she writes on her website describing the premise of the book.

Lamott is a progressive writer. She married for the first time at the age of 65, and has been sober for 37 years. She shares a life with her husband, Neal Allen, who is also a writer, her son Sam Lamott, and her grandson. Her family makes up the main characters throughout the book, reminiscing on escapades together.

“To have a heavy-hitting writer here is just wonderful, I have been following her since San Francisco, and when I heard she was in Poughkeepsie I bought tickets right away,” said Lamott fan Suzanne Sagan.

The Bardavon audience was filled with women from the ages of 34-70, some were able to convince their husbands to tag along and listen to the conversation. All attentive to her, laughing at the jokes and even attempting to sing her happy birthday.

Conversation topics ranged from the themes in her book, to sobriety, to telling stories about being a mother.

Learning about how to help yourself first, if you want to feel the love you have to spread the love, aging, relationships, having your cup filled full with your own water, and learning from your mistakes.

“That’s what life is like, slipping on a cosmic banana,” Lamott declared.

“As with all of her deceivingly simply rendered pieces, Lamott’s foibles are central to the 12 stories told here. Reconciling her own flaws as the key to tolerance is implied. Falling short is a given, especially when seeking to understand folks whose views are different from hers, particularly when they’re on the political spectrum. But demonstrating love to those who cause harm just might be too much of a reach for her — that stuff is for saints; it’s next-level wellness. Yet, Lamott strives,” Denise Sullivan writes for Datebook, a San Francisco Arts and Entertainment Guide.

Lamott was able to quote well known names such as Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Fisher, and Mother Theresa. During the conversation, she often turned to quotes that helped her create the mindset she has today, and spreads to the audience.

The talk was presented by Oblong Books in partnership with Bardavon Presents.

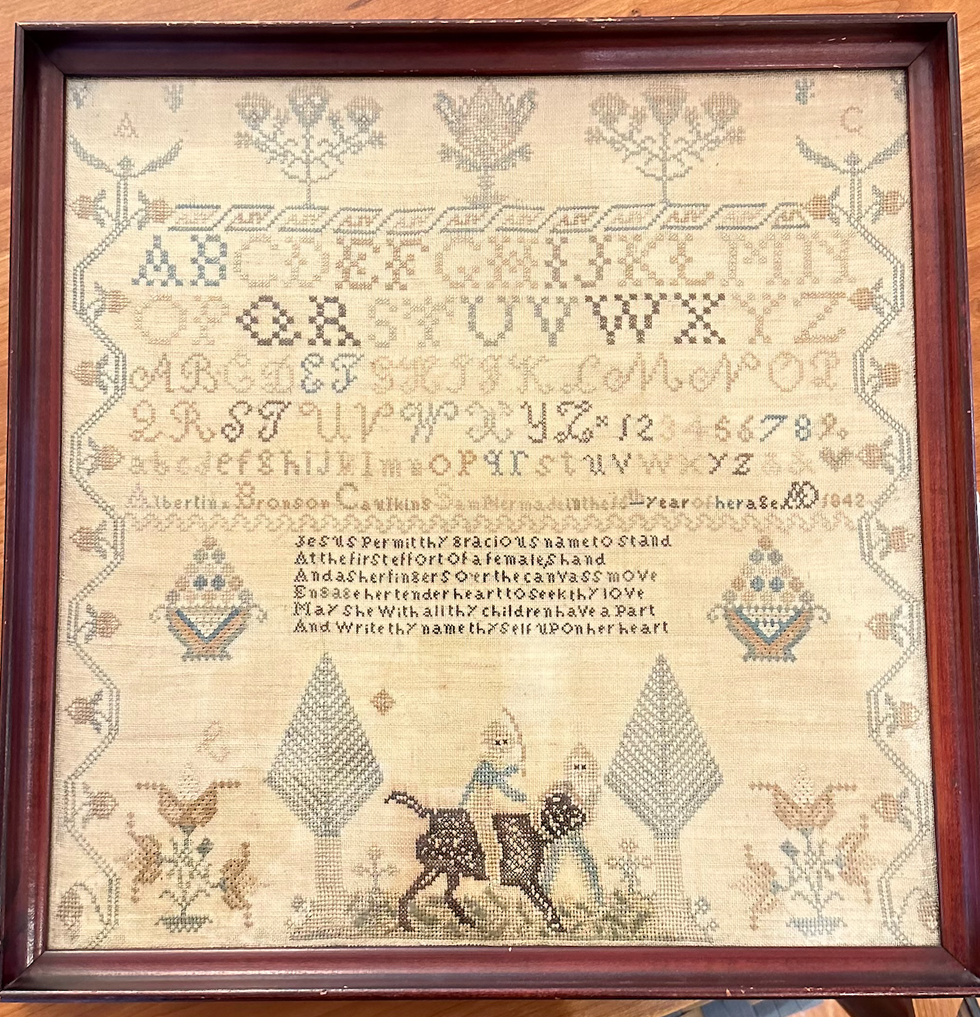

Alexandra Peter's collection of historic samplers includes items from the family of "The House of the Seven Gables" author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The home in Sharon that Alexandra Peters and her husband, Fred, have owned for the past 20 years feels like a mini museum. As you walk through the downstairs rooms, you’ll see dozens of examples from her needlework sampler collection. Some are simple and crude, others are sophisticated and complex. Some are framed, some lie loose on the dining table.

Many of them have museum cards, explaining where those samplers came from and why they are important.

It’s not that Peters has delusions of grandeur, with those small black or white cards a part of the fantasy. In the past few years, her samplers have gone on outings to historical societies and exhibits. Those small black cards are souvenirs.

About 27 of the pieces from Peters’ collection have just left home again, and are featured at the Litchfield History Museum of the Litchfield Historical Society in an exhibit that Peters guest curated along with the historical society’s curator of collections, Alex Dubois.

The exhibit is called “With Their Busy Needles,” and it opens with a reception on Friday, April 26, from 6 to 8 p.m. (The exhibit will remain open until the end of November.) Peters will give a talk called “Know My Name: How Schoolgirls’ Samplers Created a Remarkable History” at the museum on Sunday, May 5, at 3 p.m.

Although Peters was first attracted to samplers as a form of art and craft, she has come to see them as something more profound. Each sampler tells a story, but you have to know how to read between the lines of thread and fabric. Peters has become an able and eloquent curator of what were once educational tools just for young girls and women. She can look at one and give an educated guess about who made it, how old they were, where they lived and how affluent their family was (or wasn’t).

Some samplers were made on linen, others were made with silk. Some linens are fine, others are rough and homespun.

“Some of my favorites are made on what’s called ‘linsey woolsey,’” Peters said. “It’s a mix of linen and wool that’s been dyed green. It was uncomfortable to wear, but it looks great on a sampler!”

Younger girls often worked first on learning darning stitches, and would make simple samplers with letters of the alphabet. More advanced stitchers might create genealogies or family trees. Peters particularly loves to find multiple examples from one family.

“I have a couple sets that were done by sisters,” she said, “and a collection from the family of Nathaniel Hawthorne,” the American author of “The Scarlet Letter.”

All samplers, though, show the importance of girls within families, Peters said.

“Parents were excited about their girls getting an education and coming out in the world and displaying their accomplishments. It’s different from what we think.”

“We tend to scorn or disrespect things made by women, particularly if they’re domestic. But before the Industrial Revolution, all work was done at the home, by women and by men. There weren’t jobs that you went to, you did the work at home. Samplers, and needlework, are the work of women, the work of girls.”

Samplers were rarely sold, Peters said, except ones made to help Southern Blacks to escape slavery.

“They were made anonymously and sold at anti-slavery fairs from the 1830s to the 1860s. I have one that can be used as a potholder and it says, ‘Any holder but a slaveholder.’ I have another that must have been a table runner that says, ‘We’s free!’ We’d see some of them as offensive now, but they weren’t at the time; they were joyful.”

Every sampler tells a story, and Peters is an able and entertaining interpreter of those tales. Learn more by visiting the Litchfield History Museum and seeing the exhibit (complete with explanatory museum cards) and come for her talk about samplers on May 5. Register for the opening reception and for the talk at www.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/exhibitions.