Hear the word “philosophy” and feel your eyes rolling? Many people equate it to lengthy existential conversations that a bunch of old guys pondered back in the day. But there is some very real value in philosophy in today’s society. Just ask the authors of The Good Life Method, a modern-day guide to help you navigate living a meaningful life.

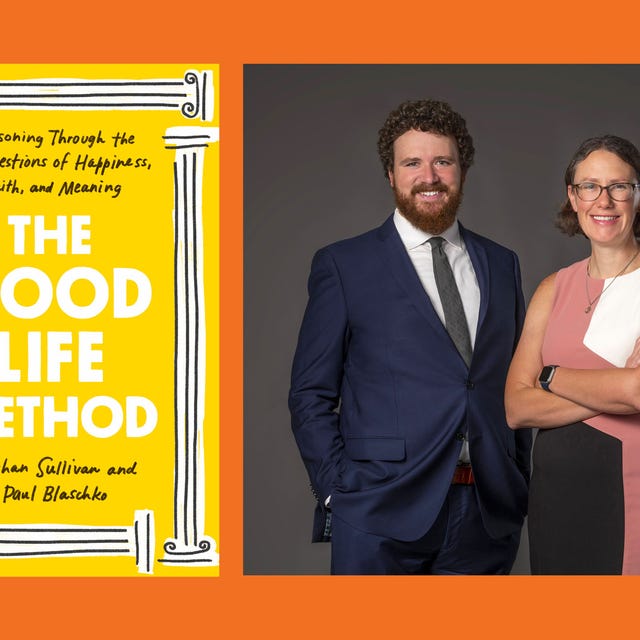

Notre Dame professors Meghan Sullivan and Paul Blaschko taught a popular philosophy course, “God and the Good Life,” which inspired their book. “After that first semester, we started getting invitations from adult groups to talk about God and the good life,” says Sullivan. “Parents of kids in our classes were asking us to help them navigate midlife roadblocks, and we realized there’s a bigger audience than just 19-to-20-year-olds.”

So, what exactly does it mean to have a philosophical conversation? How can we partake? And what benefit can it bring to our modern-day lives? Shondaland caught up with Sullivan and Blaschko to find out.

NICOLE PAJER: What is the concept of “the good life” all about?

PAUL BLASCHKO: We’re really talking about a kind of philosophy that goes back to Aristotle and Plato and Socrates, virtue ethics. The basic gist is with respect to almost anything — a human person, an animal, an inanimate object — you can think really hard about what makes that thing good or excellent if you know what its purpose or function is. The example I use in class is what makes for an excellent knife? You have to think, “Well, a knife is used for cutting things. So, the things that make it good are being sharp or the fact that it’s made out of a certain kind of material.” Aristotle realized we can do the exact same thing with our lives. So, we can ask, “What is our distinctive purpose or function?” And the answer Aristotle had was to think reflectively and seriously to contemplate the good things in our lives, and to use that ability to structure and order our lives. We can use that knowledge to define excellence for human life, and then in a really practical way just to consider what we would need to do. What habits would we need to acquire? What virtues would we need to gain if we want to actually realize and live out a good life?

NP: What are some ways that people can apply some of the practices of this good-life philosophy to their everyday lives?

MEGHAN SULLIVAN: A lot of folks think philosophy is something that you do in your own head by yourself. But philosophers in this civilized tradition oftentimes recommend that you learn how to have better philosophical conversations with people that you love and care about or are sharing your life with, because that’s how you’re going to start to learn a little bit more about yourself. You’re going to start to uncover some of your more important reasons for doing things, which is a big part of philosophy.

You get into a prosecutor’s question about the good life when you want to put somebody else in the spot. So, I’m about to go see my mom in Virginia, and she’s a smoker. I could come in hot and say, “Why do you still smoke? You have a grandchild. What are you thinking?” It’s a question that sounds like I’m trying to get her to tell me how she thinks about health. But in fact, I’m just trying to put her on the spot so I can argue with her. That is not a constructive way to do philosophy.

Socrates spent his entire career trying to get people to think about questions in a different way. A better way to start these conversations is what we call the “dinner party” questions. [It’s a] discipline of trying to ask other people philosophical questions about themselves and their lives that you don’t think you already know the answer to or are open to discovering what happens next.

One of the first things to [do is] get some practice being more curious about other people’s answers to these moral and spiritual questions. Try asking people to tell stories about the philosophically significant values or ideas that they have. So, if you found out somebody is not religious but came from a religious family, rather than trying to go in directly like “Do you think God exists?” try asking questions about what has been somebody’s experience before with organized religion. What are their earliest memories of having thoughts about this? What were their beliefs that they formed as a result of this? Those questions will help you develop more intimacy and trust with people and learn how to appreciate them as somebody who’s seeking answers.

PB: One of the practices we recommend in the book is learning how to tell good stories that can help you grow morally. One of the figures we talk about in the book is Elizabeth Anscombe. And one of her core insights is that we use stories all the time in our relationships with other people, and sometimes to excuse ourselves from doing certain things. So, if I’m running late to a meeting, I might walk in and say, “Ah, the traffic was so bad. I couldn’t possibly have gotten here on time.” Try telling stories to take responsibility. Go into the same meeting and say, “Gosh, sorry, guys. I didn’t plan well enough in advance.”

MS: I’ve been trying to use more realistic vocabulary in emails at work. So, instead of just shooting off a two-sentence email about what needs to be done after a meeting, I say things like: “I thought it was really courageous how you brought up that point. I was a little bit hurried and not totally responsible for preparing the agenda.” I try to use terms that show a dimension that is more reflection and openness to moral discussion in small ways that also expand the vocabulary of the people that I work with to realize I’m comfortable with them having those conversations with me, and they see me taking responsibility. I’m also trying to be cognizant of what is really my responsibility or the circumstances that I work in. Try getting a little bit more comfortable talking about your own virtues and vices on a small scale in transactional things like sending emails debriefing a meeting.

PB: Our final assignment for students is writing a philosophical apology. In philosophy, apologies are explanations of what you believe but also stories from your life that help explain why you believe what you believe. They end up writing their philosophical life stories, answering questions like: Should you practice a religion? How should you treat other people? And how did you come to those beliefs? What makes life meaningful? If you want to take the new year as an opportunity to reflect on the big picture, try thinking about constructing one of these apologies. Start with a statement like “What is it that I believe, and why do I believe those things?” Then find stories that illustrate your commitment to those beliefs. When are times when your beliefs have been tested? And how did you come out on the other side? When have you changed your mind? What are some big beliefs about the world that you ended up changing as a result of some of these experiences?

NP: What are some of the benefits of embracing philosophy?

PB: One of the powerful things I’ve noticed in my personal relationships is the way it allows you to reframe sometimes really difficult discussions. I talk to my mom about politics all the time. We debate. And as things have gotten more polarized, that’s a skill that’s become more difficult. Plato has this wonderful image in The Republic, his most famous book, where he says it can be difficult to try to find the truth. It can be really painful. You have this image of a prisoner trying to get out of a cave where they’re kept in darkness. They think this is the world all around us. Then they get out of the cave, and suddenly they’re in the sunlight, and their eyes are burning, and they realize, “I’m finally seeing the world for what it really is.” He gives us this image where it’s important to love the truth and to pursue the truth, but it’s really difficult.

Bringing that attitude into relationships with other people can really make the difference in changing a conversation from a prosecutorial conversation to one where you’re actually on the same team as the person that you’re talking to. So, just by realizing, “Look, even if we really disagree about something, even if we both feel extremely strongly about it, we have the same goal.” My mom and I, at the end of the day, both want the same thing. We both want to know what the truth is. That can be a really good way of reframing things and growing in our relationship.

NP: How can we use philosophy to help with goal setting in 2022?

MS: Often we pick up on the same goals that our friends are all picking up on. So, if my friends say they’re going to stop eating gluten, I will just make that my goal because they’re all doing it too, without thinking too much about why it matters to me. I’ll probably give up on the goal in a month as a result, because I don’t really understand why I’m doing it and never managed to connect it with the rest of my life.

Philosophy is really good at trying to get two or three steps more down the road and deeper about why something is your goal. So, if I say, “Well, this year I’m going to sign up to teach summer school. I’m going to really make it my goal to make more money.” Well, then the philosophical follow-up question is “Why is money such an important part of my good life right now?” Maybe it’s so I can pay for my kid’s college education. Or maybe you just think, “I don’t know why. I’ve just been tempted to keep track of how well my life is going by how much is in my bank account this year.”

If you do a little bit of philosophy about the first version of that, that might become a much more significant goal for you this year. Whereas realizing that you’re just using money to keep an arbitrary score, maybe you don’t want to rearrange your life or at least your summer vacation to try to earn more. So, philosophy can help us get deeper and more serious about our goals earlier on before we make a big time investment in it.

Imagine becoming the kind of person who, when somebody asks you why are you doing something — exercising that much or changing jobs or sending your kids to that school — you can have a much deeper answer to all those “why” questions. Do the work to be the kind of person that a year from now when you get those questions, you have a really thoughtful answer.

Another thing philosophy can do is help you realize there’s more to the good. Setting goals is an important part of pursuing what the philosophers in our tradition call eudaemonia — the good life. But there’s also an important dimension that is happiness and flourishing as human beings. That’s not goal-directed; it’s contemplative. It’s the part of your mind and the part of you that appreciates and comes to see the good things that are in [your] life.

One of your paradoxical goals in the new year might be becoming the kind of person who doesn’t just measure how well their life is going based on progress toward outside goals. Instead, develop daily practices of being able to reflect on the philosophical meaning of the things that are happening in your life: your kids growing up around you, how you are changing as a person and cultivating. After two years of volatility and running in the rat race [with] people thinking about how their lives have changed, make this the year to decide you want to take stock and be a bit more reflective rather than the kind of person that just jumps into goals.

NP: What do you hope people take away from this book?

MS: So, we want people to realize they already like philosophy; they just probably don’t know that it’s philosophy. Any time you ask yourself “why” questions, “am I doing this right?” kind of questions — am I in the right job? Am I doing the right thing? What’s going to make me really happy in the coming year? — you’re asking yourself a philosophical question. Philosophy for 2,500 years has been in the business of trying to help people think in a more serious and more sustained and more productive way about what will fulfill them and make them happy.

Also, if you find yourself at a crossroads and are feeling like “Oh, my gosh, every time I set goals, I’ve missed the mark, or the world changes on me really fast, and I’ve got to recalibrate,” philosophy can help you do a better job at answering these “why am I doing what I’m doing?” questions. It can also help you make some hard decisions about the right life choices. Knowing a little bit about how Plato dealt with complicated political disagreements, how Iris Murdoch helped improve her relationship with her friends — this kind of philosophical insight can go a long way for helping you pick better targets to be spending your time and energy on.

NP: What are some other resources people can use to start exploring philosophy?

PB: Our course is online at godandgoodlife.nd.edu. We put up a lot of the text we’re teaching our students and questions you can journal about or that you could use to start a philosophical conversation with somebody.

MS: We give our students something from The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal or The Atlantic almost every class period that’s connected to philosophy and good life. So, the web page also has the philosophy that we see in the news all the time, which gives you stuff to talk about with other people.

PB: Daily Stoic has some really great introductions to philosophy. There’s a series on YouTube called “Crash Course Philosophy.”

MS: If you’re looking for questions that get you into really interesting philosophical territory with friends pretty quickly, something I’ve used with a bunch of folks was the New York Times article “The 36 Questions That Lead to Love.” They start off kind of gentle and get more and more philosophical. This can give you things to talk about with others on a walk, family drive, or if you’re just looking for ways to initiate a philosophical conversation.

In the book, we also talk about this movement called Effective Altruism, which we’re critical of, but they’ve written a lot of interesting public-facing popular philosophy books. There’s a book called The Most Good You Can Do by Peter Singer. This gives you questions to help look at your routines, work, and home life to see how you serve the world. James Martin’s The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything can also get you thinking.

Nicole Pajer is a freelance writer whose work has been published in The New York Times, AARP, Woman’s Day, Parade, Men’s Journal, Wired, Emmy Magazine, and others. Keep up with her adventures on Twitter at @nicolepajer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY