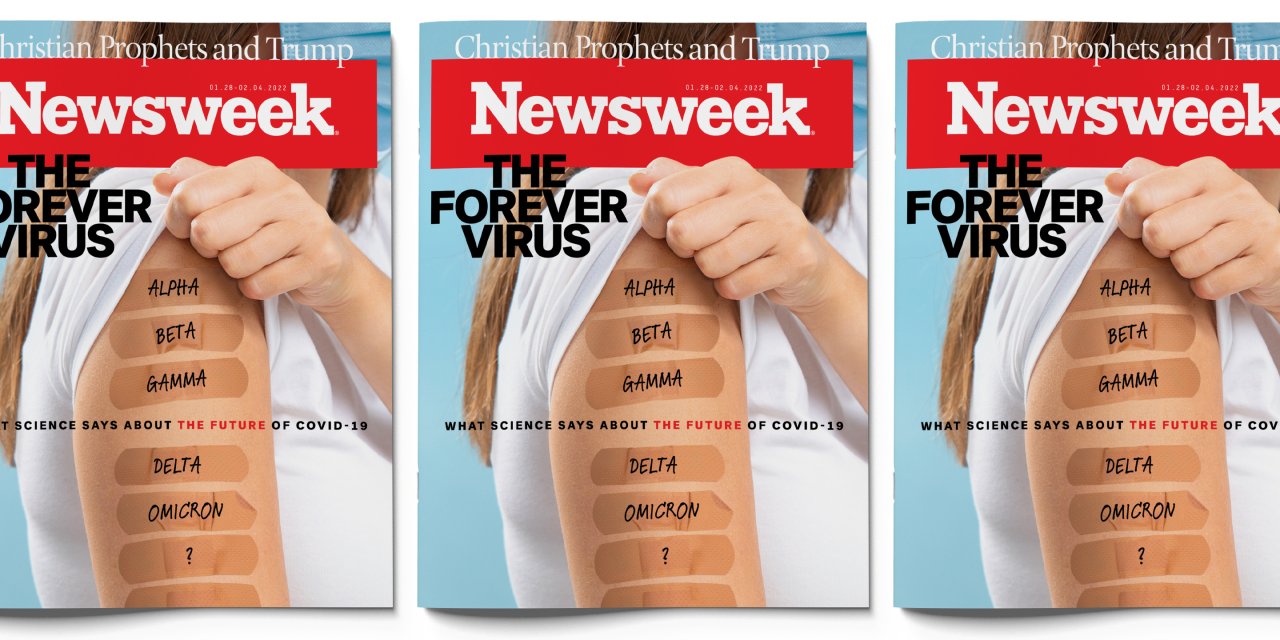

The Omicron wave currently washing over the world may soon hit its peak. According to the scientists at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington (IHME), which runs computer models of the pandemic, the number of daily reported cases in the United States was expected to hit a maximum of 1.2 million by January 19, and then decline. If the pattern of South Africa holds up in the U.S., that decline will be steep.

It is possible, but far from certain, that the Omicron onslaught marks the beginning of the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. The optimistic scenario goes something like this: Once Omicron is through ravaging the world, enough people will have acquired natural immunity that, together with those who have been vaccinated, the virus is suppressed to more or less permanently low levels in the population. When—if—that happy day arrives, the world will begin making the transition from continual crisis to something more manageable—a slow-boiling concern that keeps scientists and public-health officials occupied but leaves the rest of humanity free to go about the daily business of life.

The pessimistic scenario, which unfortunately is equally valid, starts with that familiar bugaboo: the random threat of some new, unforeseen mutation of the COVID-19 virus rising up and dashing our hopes. In this view, Omicron subsides only to be replaced by yet another troublesome new variant that causes more illness and death and extends the pandemic.

It's too early to know which scenario best describes the near future, and will probably be knowable only in retrospect. But one thing is reasonably certain: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is not going away. Scientists are in near-universal agreement that the virus will be a fixture for generations to come.

Even if the pandemic soon winds down, it's not clear what our future with SARS-CoV-2 will look like. Will the virus morph into something benign like the common cold? Or will it pester us like influenza, requiring yearly shots and constant vigilance for the next pandemic? Or will it break with convention entirely and follow some new, horrific path? Scientists are calling on the Biden administration to take steps to cope with the long-term implications of living with SARS-CoV-2.

Meanwhile, the pandemic isn't over yet. With billions of people left to infect, Omicron still has plenty of maneuvering room for mischief. It has overtaken the Delta variant in 110 countries, says the World Health Organization (WHO). That includes the U.S., where case counts have soared to more than three times the previous peak seen in January 2021. It is so highly infectious, for the vaccinated and unvaccinated alike, that in the next two or three months, IHME scientists say, it could infect three billion people—more than a third of the world's population.

"I am hopeful that in the big, big picture things are getting better," says Jonathan Eisen, an evolutionary biologist at U.C. Davis. "But when one actually looks at the details, that hope needs to be tempered by the facts on the ground. And those facts are seriously troubling."

The Wave

The most troubling fact about the present moment is the speed and magnitude of the Omicron outbreak, which stands to inflict a great deal more suffering and death.

The good news is that Omicron causes less severe illness than the original virus in 2020, or the Delta variant last year. Based on data scientists have been compiling regularly from national health agencies—particularly, in this case, from South Africa, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Norway—the team at the University of Washington has estimated that "over 90 percent and perhaps even as high as 95 percent" of people who are infected will have no symptoms. Many may never even know they had the virus. And the fatality rate, based on the reports from those countries, "is probably 90-96 percent lower for Omicron than for Delta," the variant that caused such pain and death last year.

The sheer numbers of people being infected all at once, however, is straining hospitals and public health systems—even a less-severe virus that is so highly contagious will put a lot of people in the hospital. Omicron is also proving to be a significant threat to vulnerable populations, such as people who are old or have compromised immune systems. Unvaccinated people may be as much as 13 times as likely to die as those who are fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control. Vaccination rates in some of the world's poorest countries are a sixth of what they are in the United States. And the effects of "long COVID," in which symptoms last for months or years, are poorly understood.

As to what happens immediately after the current Omicron wave subsides, scientists are divided. Ali Mokdad, an epidemiologist at IHME, sounds an optimistic note. "After Omicron—sometime around March, April—this will be behind us," he says. "Short of a new variant popping up, we'll feel that we are in a very good position. Not normal—we're not going to be normal until we are sure no new variants are surfacing. But we will be in a much better position—our hospitals will not be overwhelmed, our medical staff will get a break, people will travel, things will change."

Eisen, though, says there aren't hard numbers to support the view that Omicron will increase people's immunity enough to stem the rise of new variants. "I see it all over the place," he says. "It is based largely on hope and not data."

Confounding Evolution

There's broad agreement that—eventually—SARS-CoV-2 will become "endemic," meaning it will more or less fade into the background, flaring up occasionally, perhaps once in a while reaching pandemic levels, perhaps requiring vaccinations to stem outbreaks. But overall, the expectation is that it will settle into something more like one of the many infectious diseases we already live with, such as HIV, influenza, or RSV, which usually causes cold-like symptoms but can be dangerous to young children and older people.

"We can pretty definitely say the virus is here to stay," says Josh Michaud, associate director of global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. "While it might be a forever virus, I don't think it will be a forever crisis."

That expectation comes mainly from the history of other infectious diseases rather than any fundamental knowledge about SARS-CoV-2. What role the virus will play in our future is something of a mystery. "Something that gets lost in all these conversations is that we're still dealing with a novel coronavirus," says Dr. Preeti Malani, the chief health officer and a professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Michigan. "No one has ever experienced this."

The conventional wisdom about viruses is that they tend to become more mild as time goes by. The seasonal cold viruses currently in circulation tend to be mild relative to COVID-19, for instance. Since these viruses have been around a long time, little is known about their origins. Still, some scientists think that SARS-CoV-2 will eventually assume a place as a benign endemic virus.

This view holds that viruses evolve to become less harmful because that makes for an effective survival strategy. If a variant makes its hosts too sick to get out of bed, or if it kills them, that will inhibit its ability to spread, and it will die out. The variants that survive are the ones that are easily transmitted, which favors those that are less likely to cause immobility and death. Over time, natural selection steers a deadly virus in the direction of becoming milder, a process called "attenuation."

Want to hear more about this week's cover story?

— Newsweek (@Newsweek) January 20, 2022

Check out our Twitter Space with author @fredguterl and experts @AliHMokdad and @PreetiNMalani:https://t.co/XQCxifKzij

SARS-CoV-2 fits this mold, says Paul Ewald, a biologist at the University of Louisville. The most recent variant, Omicron, is three times more transmissible than the original virus of 2020, according to the WHO, as well as being less deadly. In early 2020 about 6 percent of patients died of COVID-19; recently in the U.S., the number is closer to 1.3 percent. Certainly, treatments have become more effective, as new medications are developed and hospitals learn how better to handle patients. But the virus has changed as well.

So have humans. Since SARS-CoV-2 invaded our lives two years ago, we've become more resilient. In America, the CDC says about 63 percent of the population is fully vaccinated, and people who have been infected have probably developed antibodies that offer at least temporary protection against the virus.

"Once you get a high proportion of the population with some immunity—and we're getting close to that now—then you'll have each successive variant causing less and less of a problem," says Ewald. "First, because of immunity, but also because of this evolutionary trend, which is that each successive one tends to be more mild."

"Despite a lot of confusion at the start," he says, "it looks like both Delta and especially Omicron are less harmful than the viruses that originally got into humans. And that's exactly what we'd expect, what we predicted to occur right at the outset."

Not all scientists agree. Eisen points out that, when it comes to COVID-19, we only have data on a handful of variants, such as the original, Alpha, Delta and Omicron. That is too few to prove Ewald's argument. In addition, Eisen says Delta was actually more harmful to its hosts than Alpha, which it supplanted as the dominant strain.

"The virus is not evolving generally to being less deadly," he wrote in an email. "We have one crazy variant, Omicron, which does appear to be causing on average less severe disease in vaccinated people. But the previous dominant variant (Delta) was way more severe than the dominant ones before it. So they are using one single data point (Omicron) to conclude that there is a trend? That seems completely unsound scientifically."

Even if SARS-CoV-2 eventually becomes just another relatively harmless virus, that evolution could take years. In the meantime, scientists are trying to figure out how the virus might be managed with vaccines. For clues, they've been looking to existing coronaviruses.

For instance, studies of HCoV-229E, a coronavirus that causes colds and pneumonia, suggest that the virus tends to reinfect people every few years by developing some ability to evade immune-system protections. Indeed, Omicron, which is successful in large part because it can infect both people who have been vaccinated and those who have had prior infections, seems to have taken a page from 229E's playbook. It's reasonable to assume that future variants of SARS-CoV-2 will continue this practice.

When SARS-CoV-2 eventually settles into a new role as an endemic virus, it doesn't mean outbreaks will become a thing of the past. Influenza and coronaviruses flare up now and again, sometimes becoming pandemics. The question is how troublesome will these outbreaks be and how will public health officials manage them?

SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely to play out like measles, where childhood vaccination confers immunity for life. It's somewhat more likely that vaccinations during childhood could protect people well into adulthood against severe disease. Or the virus could turn out to be something more troubling, like influenza, which evolves quickly to evade immune-system protections and requires vaccination every year against new variants. Another yearly shot wouldn't be pleasant, but it's not the worst fate.

That said, there's no law that SARS-CoV-2 has to behave like other viruses have in the past. Indeed, a UK government advisory group last summer raised the chilling possibility that SARS-CoV-2 could take up the habit of recombining with other coronaviruses to take on troublesome new forms. The virus, hemmed in by vaccinations and immunity from prior infections, might then gain a wealth of new features, including the ability to cause more severe disease than previous versions, evade vaccines and resist anti-viral treatments. The report called each of these three scenarios a "realistic possibility."

Preparing for Forever

Most people tend to look at vaccination in terms of whether the (tiny) risk to themselves is worth the (much larger) risk of contracting the disease. This is understandable. What often goes underappreciated, though, is the role vaccination plays in the global strategy to contain a destructive virus on the loose. Any discussion of the future of SARS-CoV-2 inevitably includes the status of vaccinations.

The reason is the longer a virus persists in the wild, replicating and mutating among billions of people, the more likely it is to hit the genetic lottery and morph into something that makes people's lives miserable (or kills them). Once these variants arise, they won't necessarily ever go away.

That's also why so many scientists and public health officials are reluctant to start pouring the champagne yet. "We know that the more the virus spreads, the more it replicates, the more it mutates, and there will be more variants," says Dr. Céline Gounder, an infectious disease expert at New York University's medical school. "I would be very careful about jumping to the conclusion that after this Omicron surge, we're going to hit 'endemic,' or we'll all have enough immunity that it's just a common cold. I just don't think we know that right now."

Dr. Gounder, who was part of then President-elect Biden's COVID-19 advisory board, and five colleagues have written a polite but pointed public appeal to the White House to stop promising to "gain the upper hand" against the virus and start making long-term plans that accept it as the new normal.

"We keep saying, 'Oh, this will be the last wave, and we can move on,' when that's not the case," she says. "And I think we really need to say, 'All right, we're going to live with it.' We then need to act like that and come up with a long-term plan."

The advisory board members call for a reset of the administration's COVID-19 policy—with a new emphasis on testing and free N95 masks and less reliance on vaccines. "That's not to say vaccines are not important—they're the number one, number two, number three most important tools in the toolbox—but when you're dealing with an American public where we have hit a plateau with vaccinations, vaccines are not going to do it alone," she says.

The plan includes a dramatic rebuilding of America's public health system, which languished in the years before COVID. It calls for a new corps of healthcare workers who reach out to people in times of crisis. It recommends vaccines that work against many different respiratory illnesses instead of being targeted only at the virus of the moment. Better ventilation systems for schools and other public places—new heating and air conditioning—could make a big difference, considering how much has been learned about the spread of airborne viruses. Above all, they say, the U.S. needs to plan years into the future, since COVID-19 is far from gone and future pandemics could spring quickly from just one genetic mutation.

"I really hope we learn the lesson," says Dr. Gounder. "That's why we're doing the kind of advocacy we are, because we're frankly terrified what will happen if we don't."

Public health specialists are also calling for better, more modern alert systems to warn them immediately of new outbreaks. Testing kits should be simpler and far easier to get. And, though many people may hate it, we will probably need regular vaccinations for a very long time. Such things, of course, cost money, but America's gross domestic product already stands to shrink by $8 trillion between now and 2030 because of the pandemic, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Advocates also urge more attention to the rest of the world—not just out of humanitarian concern but as a matter of self-protection. A team at Texas Children's Hospital in Houston, led by Drs. Maria Elena Bottazzi and Peter Hotez, has developed a vaccine called Corbevax—and handed it off, patent-free, to an Indian drug company. It's based on medical technology from the 1980s, much less sophisticated than the vaccines used in the U.S., but remarkably cheap. A dose might cost a dollar or two. The development money came from philanthropies. Hotez has called it a "global game changer," especially if other less-wealthy countries make use of it.

Predictable Crisis

At some point, pandemics do end, no matter how well or badly they were handled. The so-called Spanish flu of 1918-1920, spreading across a world already ravaged by World War I, may have killed 50 million people, including an estimated 675,000 Americans—this in a country less than a third as populous as it is today.

In 1918, there were no vaccines, no social distancing, no great medical breakthroughs. The pandemic lasted two years, through four deadly waves, and then faded out, largely because the virus ran out of victims. A majority of people were probably infected, with a fatality rate of 2.5 percent in the U.S. and an estimated 10 to 20 percent worldwide.

The virus also evolved to become less deadly, which may be one reason why it is still with us. Now known as H1N1, it is still one of many strains of seasonal flu circulating around the planet. (It was never actually "Spanish," by the way—the name caught on because the government of Spain, neutral in the war, didn't try to suppress the news of it.) And while annual flu outbreaks are terrible, they don't usually paralyze the globe.

The Biden transition team doctors think Americans will consider the COVID-19 crisis over if the death rate drops to something like what seasonal flu causes. Each winter in the last decade, flu strains have caused between 12,000 and 50,000 deaths. That's a terrible toll, but it's become predictable.

"People get their vaccine and they're ready," says the University of Washington's Mokdad. "We don't shut down the government. We don't do contact tracing for flu. That's an endemic situation, and that's what you hope for from COVID-19."