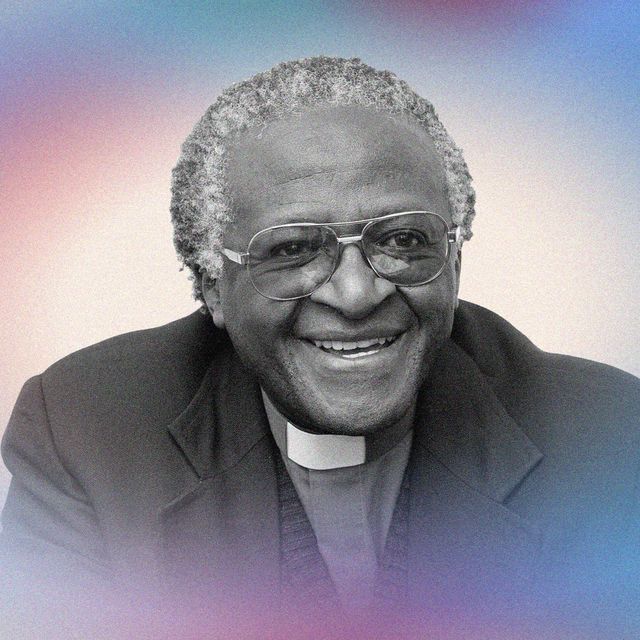

After the recent passing of Desmond Tutu, I longed to hear the interview I did with him for a book I was working on, recorded on an old cassette tape, which I held on to and hadn’t listened to in 26 years. Such a gentle, kind, and eloquent man — I have thought about his compelling words and insights over the years. His remarks are as relevant now as they were in the mid-1990s.

I first heard him speak during our 3 a.m. interview set up by his personal assistant in 1996, the most convenient hour for him, given the time difference — seven hours apart. I was living in a quiet area of Westport, Connecticut, then. There was a starless sky and silence as I waited for his call. Tutu, a Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1984 for his efforts in ending apartheid, was the archbishop of — and calling from — Cape Town, South Africa.

As anxiety looms daily from this pandemic, his words on that recording hit home. “There are many times in life when we go through periods of desolation, when we are exhausted from difficult times, feel like death warmed up, and we can’t bring ourselves to concentrate for one moment. We sense that God is removed, that He is not really present.”

Having lost one of my closest friends to AIDS only two years before this interview, I had my own questions about God then, as I sometimes have now living in New York City, where I’ve lived most of my life, after losing loved ones to Covid. Tutu was an advocate in the fight against AIDS and a gay-rights advocate, despite criticism from African religious leaders. He also urged South African citizens to take Covid-19 vaccines when they became available and pledged to do the same as hundreds of thousands of South Africans and people throughout Africa were losing their lives. Though he acknowledged that one tends to doubt God’s presence in times of adversity, he was a man of great faith.

“When you are in the presence of the Holy Spirit, it is like sitting in front of a fire that does not burn you. You are drawn to the qualities of the fire — its warmth, glow, and color. And as you are there in the presence of the Spirit, you also become suffused with the divine attributes of compassion, gentleness, and love, without your doing anything about it except just being there. You are loved, and you are held in this love,” he said in our taped conversation.

I was struck by how Tutu used the image of fire when speaking about God’s Spirit. There is something mystical about the candles we light for the dead, or for Sabbath, or Advent, or other religious holidays. Or the candles we light on our birthdays. I have sometimes felt my birthday wishes are like prayers, that if I close my eyes and silently hope, my wishes might come true. That something divine is at work, and anything divine feels like love.

After my friend died of AIDS, I prayed for understanding and peace in the awkward way that Tutu said often happens when we are broken. “When we are really low, feeling awful, we assume our prayer is probably useless. Yet it’s still moving forward, almost like a river. We just have to lie down in the stream and allow the current to carry us.” For those who believe that God is listening to their prayers, this is easier to do than for nonbelievers who turn to prayer when they are desperate. Yet to even attempt to pray without faith is faith.

I sat in hospital waiting rooms in the ’90s during the AIDS epidemic, and in lines, socially distanced with masked strangers, in this hellish roller coaster of a pandemic, exchanging silence, comfortably avoiding one another, as we waited for updates about our loved ones or test results for ourselves. Occasionally, in the waiting rooms or in the lines, I would hear a mumbled prayer, even just a “Please, God” escape from someone, or myself, like a sigh. As strangers waiting together, we didn’t want to know one another, or to be known. Yet even the smallest prayer is an act of communication.

“Think of prayer as a relationship,” Tutu said. “If you are in a relationship and you don’t have any communication, then that relationship is not going to grow. I think of prayer, clearly, as being in the acknowledged presence of God and in relationship with God.”

Tutu considered prayer to be a ritual, something he did daily whether he was inspired to or not. He felt that prayer, like creating art, involved discipline, and that often the inspiration came during prayer, not before.

“In the early days when I was still young, I was being trained in techniques of prayer. But as I have grown older and have learned from others more experienced in the ways of the Spirit, I have become more and more aware that it does not depend on techniques or how I feel when it comes to rituals. It is important to know that I have set aside time — maybe in the morning, at midday, or in the evening — just to do this tangible thing that is sanctified and brings peace.”

Who, during this pandemic with so many risks, uncertain precautions, and isolation, didn’t get through it somehow with rituals? I did those 7 p.m. nightly rounds of applause, by my Manhattan apartment window, for first responders and essential health-care workers. I washed my hands with antibacterial soap every time I returned from anywhere outside. I substituted exercising inside a crowded gym that I loved for working out at home. I did these and other things, whether I felt like doing them or not, to give myself a sense of normalcy and safety during an unsafe time. But mostly to try to feel peace.

Undoubtedly, in many households, and definitely in mine, prayers were being said during the hardest times, for family and friends to be spared or recover from Covid, for loved ones we couldn’t see or touch as they were dying, or attend their burials, shivas, and wakes. Tutu, a true humanitarian, was all about offering words of hope. He was dedicated to serving others, helping them to overcome hardships. When I requested an interview with him for my book, he agreed only on the condition that it wouldn’t glorify him but would glorify God. He believed faith is what people needed most.

When I asked Tutu if there was a favorite prayer he returned to, he answered, “One that I say regularly is the prayer of Saint Francis: ‘Make me an instrument of your peace.’”

Joanna Laufer is the author of Inspired (Doubleday) and the co-creator of the best-selling Inspired classical music series on RCA. She has written for SheKnows, BrainChild, Child Magazine, Dance Spirit, and more, and her essays have been anthologized. Her fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals including Antioch Review, Fiction, Ontario Review, Greensboro Review, StoryQuartely and others. Joanna is the Associate Prose Editor of Tiferet Journal. She is a freelance manuscript editor and writing coach. Twitter: @joannalauf

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY