Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

On January 5, Liam Foster, 21, clipped the chains of Riders on the Storm (5.14-), putting down a 20-year open project in Durango, Colorado. When Foster lowered, the first thing he did was call Marcus Garcia, his mentor and coach of almost a decade. There were tears on the phone; Garcia is the one who bolted the route back in 2000. Then, he was the same age Foster is now.

When Garcia started coaching him in 2012, Foster was a high-energy 12-year-old with, we’ll say, a sub-prodigy-level aptitude for climbing. Garcia never expected the kid to grow up and send Riders, which is perhaps Durango’s longest-standing unfinished test piece.

“As a kid, Liam was really slow,” Garcia laughs. “He took forever to put his shoes on because he would get distracted. I had to tell him Velcro shoes only. I think I actually gave him a pair because I was so tired of watching him tie his shoes all the time.”

This article is free. With a membership you’ll receive Climbing in print, plus our annual special edition of Ascent and unlimited online access to thousands of ad-free stories.

But focus came, and over the years, Foster thrived under Garcia’s watch. He performed well in indoor youth bouldering and sport-climbing competitions and joined Garcia’s burgeoning youth ice-climbing team, the first of its kind in the country.

Foster went far on the international competition ice-climbing circuit, particularly in the speed discipline—Garcia’s specialty. After a time, the two became friendly rivals. At the 2017 Ouray Ice Fest speed climbing competition, Garcia beat Foster. The very next year, they traded roles. Foster has edged out his mentor at every Ouray speed competition since—a result Garcia couldn’t be more pleased with.

Over the years the two stayed in constant contact about training and climbing, as well as about other struggles in life. When Tom Ballard, a storied mountaineer and good friend of Foster’s disappeared on Nanga Parbat in 2019, he says Garcia was there for him in a big way.

“Liam still thinks of me as his coach, but at this point, we’ve just become climbing partners,” Garcia says.

One day, shortly after sending his first 5.13+/5.14-, Haiku in Colorado’s Boulder Canyon (Foster worked with coach Peter Beal to improve his finger strength and technique ahead of the send), Foster recalls lying on the floor of the climbing gym, wondering what to do next. That’s when he remembered Riders on the Storm.

“I first saw the route when I was a kid. I don’t think it was my first day rock climbing, but it might have been my first day rock climbing not in sneakers,” Liam says. “My parents had signed me up for this guided day through the Rock Lounge, the gym Marcus later owned. I looked up at this crazy overhanging arete that rose above the whole crag and said, ‘What’s that?’ The guide told me it was Marcus’s project. I said ‘Oh, sweet,’—and then turned around and proceeded to completely flail on a 5.8.”

But Riders never left his mind. After all, he could see the prow from his family’s dining room table. In 2020, Foster texted Garcia that he wanted to give it a try.

“I was honored,” Garcia recalls feeling when he got the text. “I wanted to share it.”

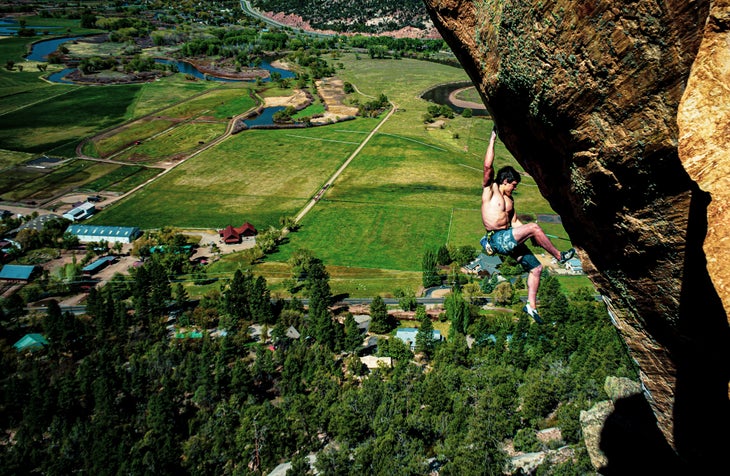

Over the next year, between semesters at the University of Colorado in Boulder, Foster kept coming back to the route. For 22 of the 38 days he spent working it, Garcia was with him. Not there to climb—just to help rig fixed lines, belay, and support his mentee on what would become the hardest route Foster had ever tried. And in between attempts, the two would sit on the belay ledge—a narrow perch about 100 feet off the ground, and talk about life.

“This route isn’t about being strong. It’s about being patient, and Liam had to learn that,” Garcia says. “He’s experienced so much growth in the years I’ve known him. It’s been a beautiful journey.”

The route’s name comes from a vicious summer storm that swept in as Garcia was putting in the bolts 21 years ago. He spent more than 30 minutes dangling in space as sheets of rain and lightning whipped around him.

“My roommate lived below the cliff across the river, and saw me hanging there and ran up the trail. He thought I was dead,” Garcia laughs. But he rode out the storm, and as he did, he realized the situation reflected where he was in life at the time.

“I was in the middle of these big life transitions,” Garcia recalls. “I was dating this girl and she broke my heart, and I was this single dirtbag climbing guide bouncing between Yosemite, Mexico, and Colorado.”

For Foster, the name also rang true; he graduated this December with a degree in physics. Returning to his childhood home in Durango, caught in the limbo between undergrad and grad school, he felt unmoored. And being home was bittersweet; in between sessions, he and Garcia would drive back to town to work on closing the Rock Lounge, which Garcia had owned for 8 years.

“We’d go to the route from 6 AM to 11 AM, give it a couple burns, and then come back down and literally disassemble the gym,” Foster says. “We had to angle-grind the bolts out of the floor that held the walls in place. Everything had to go. It was pretty emotional—that gym is where I grew up in a way.”

Then, on day 38, it all came together. The humidity was hovering below 20 percent, which Foster and Garcia had calculated to be perfect. The sun went behind the clouds. Garcia was at work, but a group of supportive friends stood at the base cheering Foster on.

When Foster stuck the low-percentage deadpoint near the top of the route, he resolved to fight. He hit the next crimp and worked his feet up to a high, waist-level smear, then stood up hard and threw for the last sloper, the final heartbreaker move—and stuck it.

“I think I yelled the loudest I’ve ever yelled in my life,” Foster says. He remembers executing the last moves slowly, savoring the moment for as long as he could. And after the chains, he topped out the arete, sat there, and looked out over his hometown, reflecting on how far he and Garcia had come.

At the bottom, he called his mentor.

“Marcus, we did it.”