Being around The Greatest, Muhammad Ali remembered

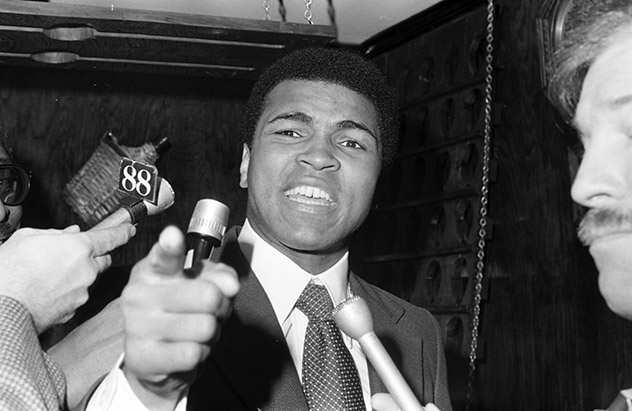

There is a widespread belief that the late, great Muhammad Ali, who would have turned 80 today had he not passed away, at 74, on June 3, 2016, was forever “on,” ready at a moment’s notice to regale large crowds or even small gatherings of his fans with the high-decibel verbosity of someone who early and often proclaimed that he was the greatest of all time. That Ali of our memories was the ultimate showman, whose public persona was a hodgepodge of influences that included, among others, a preening wrestler named Gorgeous George, Sugar Ray Robinson, Malcolm X, Elijah Muhammad, Nelson Mandela, maybe even a touch of Mother Teresa.

Mix all that with a dizzying array of boxing skills and the end result was a unique individual who elevated a brutal sport into an art form akin to Michaelangelo’s painting of ceilings. They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but while more than a few fighters have sought to pattern themselves after Ali, he was an original beyond replication, a talent so luminous that he just might have been all that he claimed to be, and a personality so compelling out of the ring that the three-time heavyweight champion was, arguably, the most widely known human being in the second half of the 20th century. Even now, more than five years after his death and 41-plus years since he last held the heavyweight title, he arguably remains the most famous boxer, or athlete, ever to have strode across the global stage.

But the Ali who outraged many and was adored by countless others during a turbulent era when I wrote that he was “perhaps the most polarizing figure in America, with the possible exception of Jane Fonda,” underwent a remarkable transformation that eventually won over a significant percentage of his harshest critics. The youthful braggadocio that was, by turns, entertaining and infuriating was toned way down by the ravages of Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological condition which over the 32 years since he was first diagnosed saw it rob him of both his verbal aplomb and physical dexterity. For a number of years as his decline became more obvious, the youthful chest-thumper variously derided by critics as the “Louisville Lip,” “Cash the Brash,” “Mighty Mouth” and “Gaseous Cassius,” although still mentally facile, was so silenced that his barely audible mumblings had to be interpreted and relayed through his fourth wife, Lonnie.

It was that Ali, virtually silent, trembling and unable to walk without assistance, who was on the stage in Philadelphia the night of Sept. 16, 2012, when he received the Liberty Medal in conjunction with the 225th anniversary of the ratification of the United States Constitution. Previous honorees included former presidents, Supreme Court justices, international dignitaries and other notable figures adjudged to be advocates of the principles of freedom. More than 2,000 spectators on the front lawn of the National Constitution Center listened and applauded as Ali was lauded as an “ambassador for peace and justice worldwide,” “a tireless humanitarian and philanthropist” and a “symbol of hope and catalyst for constructive dialogue.”

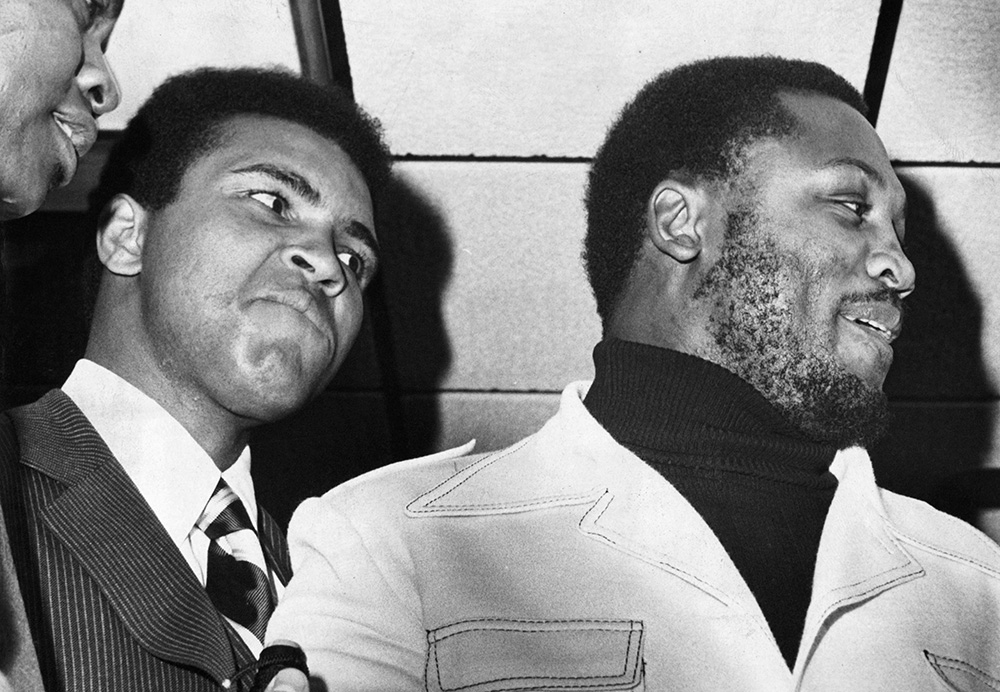

In November 2005, Ali – who by that time had undertaken missions to developing countries to deliver food and medical supplies, in addition to serving as a fundraiser for Special Olympics and the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Research Center in Phoenix – received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush in Washington. With the addition of the Liberty Medal, forgotten, or nearly so, was his cruel taunting of several opponents, most notably Joe Frazier, whom he derided as “a gorilla,” and “Uncle Tom” and “ignorant,” and his denouncement of white people as “devils.”

A brief moment of levity ahead of the heated 1974 Ali-Frazier rematch. Photo by The Ring/ Getty

At the ceremony in Philadelphia – somewhat ironically, Joe Frazier’s adopted hometown (no member of the Frazier family was in attendance) – a parade of speakers, ranging from Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett, a conservative Republican, to Philly Mayor Michael Nutter, a liberal Democrat, strode to the podium to praise Ali as everything that is fine and decent and praiseworthy.

One of the speakers, Joe Louis Barrow II, son of Joe Louis, nodded toward Ali and said, “the two of you made opposite choices – my father choosing to volunteer in World War II and you, for religious convictions, refusing to serve in Vietnam. In different ways, you both defended the ideals of the Constitution. But time has shown you were both on the right side of history.”

Joe Louis Barrow II’s take on how history ultimately will treat Ali remains to be seen; history is like an amoeba, constantly changing shape to fit time and circumstance. The guess here is that the shinier image of Ali, for the most part, will stand up well into the future, and possibly forever. Even the legendary rift that for so long had existed between Ali and Frazier, who was 67 when he passed away on Nov. 7, 2011, was mended to some extent; in The Ring’s 50th anniversary commemorative issue of the first Frazier-Ali fight, I authored a story on the long-delayed reconciliation of the two great rivals, which occurred on Feb. 8 and 9, 2002, the night before and then the night of the 53rd annual NBA All-Star Game in Philadelphia. In that story I noted that Ali and Lonnie had attended Smokin’ Joe’s funeral service in Philly, Ali’s presence marked by solemn reverence and respect, not belligerence and bombast.

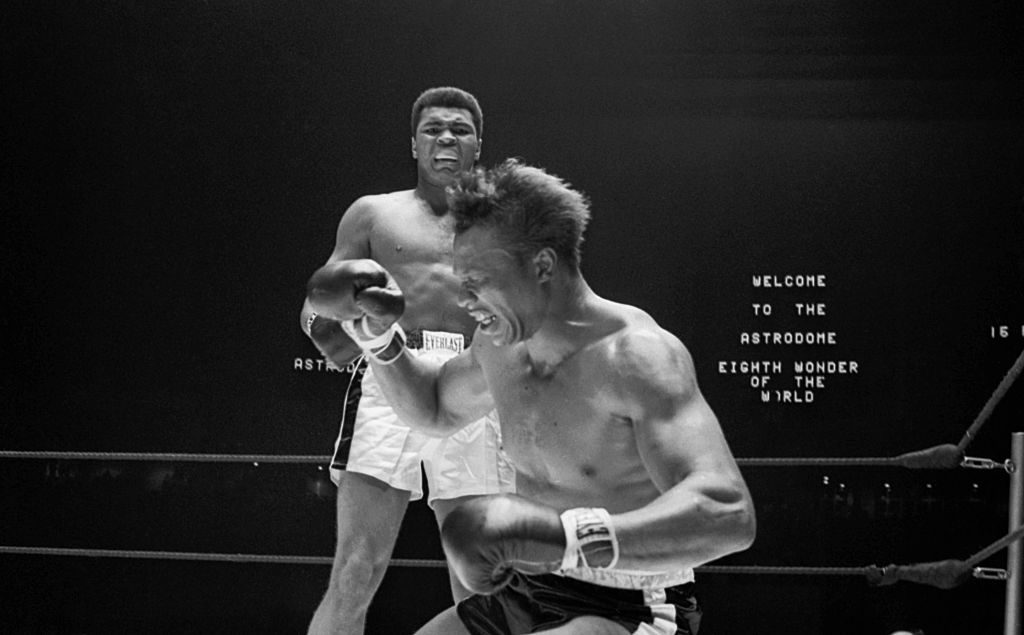

Regardless of how anyone chooses to remember Ali for other reasons, what is indisputable is his greatness as a fighter. He was arguably at the apex of his powers on Nov. 14, 1966, in Houston’s Astrodome, when the then-24-year-old retained his heavyweight championship by disassembling the dangerous Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams, the finishing sequence a rapid-fire combination that had the challenger’s skull vibrating like a bobblehead doll.

Ali floors Cleveland Williams. Photo by Bettmann/ Getty Images

Two fights later, a seventh-round stoppage of Zora Folley on March 22, 1967, in Madison Square Garden, Ali was again the picture of pugilistic perfection. And the scary thing is, he just might have become even better had his career not come to a screeching halt because of the suspension handed down for his refusal, on religious grounds, to be inducted into the Army during the Vietnam war. It would be 43 months until Ali, his boxing license restored as the result of a favorable Supreme Court ruling, fought again, a third-round TKO of Jerry Quarry on Oct. 26, 1970, in Atlanta. But that Ali, although still a superb fighter, was different – a bit heavier, a smidgeon slower, more apt to absorb punishment and fight through it than to slip punches with almost casual ease.

“Ali before the layoff was a better fighter than Ali after,” his longtime trainer, Angelo Dundee, opined in 1995. “What a lot of people don’t realize, and it’s sad, is we never saw him at his peak. The Ali who fought Cleveland Williams and Zora Folley was the best he could be at that time, but he was getting bigger and stronger and more experienced in the ring. What was he, 25 years old when they made him stop? Those next three years would have been his peak. If he had continued getting better at the rate he was going, God only knows how great he would have been.”

Throughout his career journey Ali was, of course, unabashedly vainglorious, not in the least hesitant to pronounce just how magnificent at his craft he was in relation to lesser practitioners of the pugilistic arts. “Who made me is me,” he once said. “My only fault is that I don’t realize how great I am. I am the greatest, and I said that even before I knew I was.”

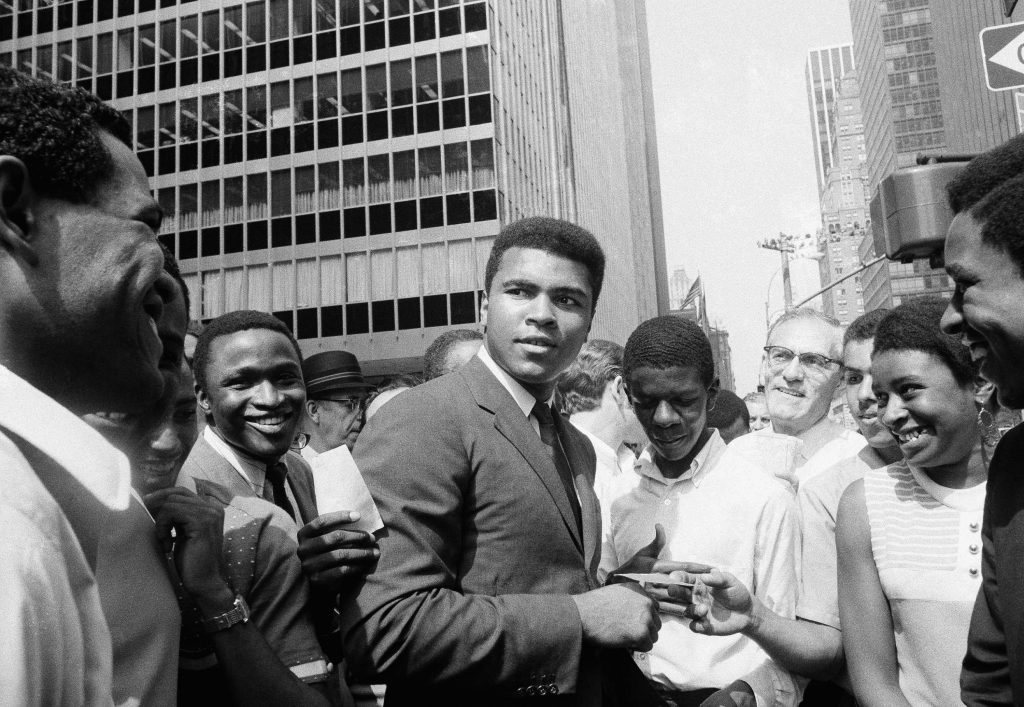

Ali was always surrounded everywhere he went. Here he is mobbed by autograph seekers in Manhattan on Aug. 23, 1968. Photo by Anthony Camerano

But all the fame and/or notoriety that Ali had set out to achieve, and did, was not without its drawbacks. His more reticent side was not often glimpsed outside of those within his inner circle, but it was something I was privileged to see up close and personal after his boxing career was over, and certain realities of his post-retirement circumstances were tamping down his incessant ebullience.

I was a sports columnist for the Jackson Daily News in Jackson, Miss., when Ali came to town in June 1983 for the Medgar Evers Homecoming, arriving not by private jet but aboard Delta flight 216, albeit in the First Class section. As photographers and television cameramen began elbowing for better position, a few bystanders also began to gather.

“Who’s the celebrity?” asked one.

“Muhammad Ali,” replied a photographer. “Muhammad Ali is on that plane.”

The word soon spread like a brushfire. Even before the travelers began to deplane, the curious few had swelled to a mini-mob. Ali, the fourth person through the line, squinted through the glare of the TV lights and the pop of flashbulbs, smiling wanly as children were produced to be kissed, women rushed forth for a hug and men extended scraps of paper for autographs. Ali dispensed his kisses and hugs and autographs with a lack of enthusiasm that was thinly veiled, and why not? There is a price to be paid for the cost of celebrity, and by then Ali probably had paid it a million times.

The routine continued at Ali’s hotel in downtown Jackson, where had been rushed by limousine. “You look like Joe Frazier,” he told a bellman in the lobby, crouching down and throwing a few playful jabs. The doorman, obviously pleased at having been singled out, broke into a wide grin. “You still the greatest, Champ,” he told Ali.

Ali (left) looking to get in an early shot on Spinks. Photo by The Ring/ Getty Images

Being The Greatest is the image Ali had worked so long and hard to create, and after a while there was no escape from it, not even occasionally. The image was self-perpetuating, able to feed on its own impetus with or without help from its creator.

Later, stretched out on a bed in his suite, shoes kicked off and tie loosened, Ali practiced magic tricks for the few members of his entourage who had accompanied him to Mississippi as well as for the sports columnist he had graciously consented temporary admittance into his private space.

“My dream,” he told me, “is to go somewhere and not be recognized. To go to the beach, to the amusement park with the kids and not have to stop and sign autographs all the time …”

Ali smiled, fully aware of the impossibility of making that particular dream reality. “Being famous is not so bad,” he said. “Everybody enjoys being recognized and admired. Anyway, you get used to it.”

Asked if he had to do everything the same if he had to do it all over again, Ali said he wouldn’t change a thing. “Yes,” he confirmed. “I’d do it exactly the same. Because all the things that ever were bad turned out to be good.

“Boxing was the bait. People are the fish. Boxing made me famous. People came to hear me talk. They still do. There’s bigger fights for me to win than anything I ever did in boxing. I intend to win those fights.”

At that moment, Ali seemed to me to be not so much a measuring stick against other great heavyweights such as Louis, Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano as of Elvis Presley. Elvis was the King of Rock ’n’ Roll, The Greatest in his own sphere, a man who was both drawn to and repelled by the limelight he so easily attracted. And I wondered if the golden cage of fame, sought by many, attained by few, was all it was cracked up to be when Muhammad Ali embarked on his quest to put himself on a pedestal unknown to any boxer.

In 2015, the United States Postal Service conducted a nationwide poll to determine which version of Elvis Presley should appear on a commemorative stamp. One version was of the 1955 lean and hip-swiveling Elvis; the other was the 1970s sequin-jump-suited and noticeably plumper Las Vegas model. The vote was, of course, a landslide for the young Elvis.

Were a similar vote be put to the American public for an Ali stamp, one being the young, sleek and impossibly gifted boxer who did things no heavyweight had done before or since, or the older, retired Ali who was cited for his humanitarian and philanthropic contributions to society, the outcome would be as preordained as had been the one for Elvis. That class of humanitarians and philanthropists might be in short supply, but they still are more plentiful than individuals who can perform feats of athletic excellence that can make mere mortals gasp in amazement.

Today, on what would be his 80th birthday, remember Muhammad Ali for what he was in both incarnations of a life well-lived.

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.