Carl Bernstein is crying. He slips an index finger behind his spectacles to push away a tear. He repeats the action to wipe his other eye.

Nearly six decades have passed since Bernstein, a young newsman in a hurry, was told by a colleague that President John F Kennedy was dead. But the gut punch of that moment surfaces as if it were yesterday. “I still have trouble with it,” Bernstein admits, quickly regaining his composure. “It’s very strange.”

Now a silver-haired 77, Bernstein is one half of the world’s most famous journalistic double act. His reporting with Washington Post colleague Bob Woodward on the Watergate break-in and cover-up helped bring down Richard Nixon (still the only US president to resign).

Their 1974 book about it, All the President’s Men, was turned into a film starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman that remains probably the most accurate Hollywood depiction of the reporting process.

Bernstein’s latest work, Chasing History, is a prequel to all that, a vivid memoir of his apprenticeship, a love letter to the trade and an elegy for the vanishing world of local newspapers. It is Bernstein without Woodward.

The book maintains a tight focus on his time at Washington’s Evening Star newspaper from 1960 to 1965, covering the Kennedy era, civil rights movement and various grisly crimes. But in a Zoom interview from his New York apartment, he proves willing to expand and expound on everything from the decline of meritocracy to former president Donald Trump to America’s cold civil war.

“I’m going all over the place, as I’m known for doing,” he cheerfully acknowledges at one point during a discursive conversation that will last an hour and three-quarters, punctuated by his wife Christine arriving home (“Hello!”) and a delivery of flowers from his publisher. “I tell stories circumlocutiously.”

Chasing History evokes a journalistic Camelot: the newsroom as humming word factory with gunmetal desks, stacks of newspapers, clattering and chinging typewriters, carbon copies of old stories impaled on spikes, men yelling “Copy!” and racing against deadline, and printing presses rumbling under the floor.

It is an era of hats, pay phones and cigarette smoke reminiscent of the 1940 film His Girl Friday, based on the play The Front Page, in which Hildy Johnson (Rosalind Russell) remarks: “A journalist? Now, what does that mean? Peeking through keyholes, chasing after fire engines, waking people up in the middle of the night and ask them if Hitler’s gonna start another war, stealing pictures off old ladies?”

There are also echoes of the Fleet Street in which Nick Tomalin identified the qualities required for success in journalism as “ratlike cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability”.

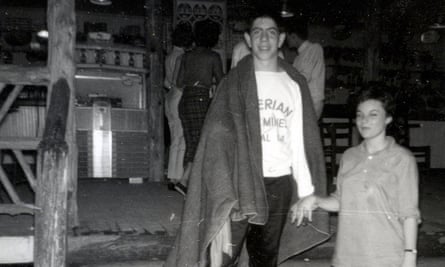

The teenage Bernstein had another asset: he could type nearly 90 words a minute after joining his school’s otherwise all-female typing class. This, combined with an assist from his father, landed him a job at the Star as a copyboy running errands when he was just 16.

With printer’s ink in his veins and a nose for secrets, Bernstein describes walking into the newsroom for the first time as the most singular moment of all his days. He is like Dorothy stepping out of monochrome into Technicolor Oz.

“In my whole life I had never heard such glorious chaos or seen such purposeful commotion as I now beheld in that newsroom,” he writes. “By the time I had walked from one end to the other, I knew that I wanted to be a newspaperman.”

He was like a puppy on a leash that day, he recalls, and was handed a late-afternoon edition that had just come off the presses, its pages still warm. He says in the interview: “I was 16 years old. I got the best seat in the country … I think the thrill never left me.”

There were great wordsmiths at the Star. One would go out on his boat on the Chesapeake Bay and encounter oystermen from remote communities who still spoke with an Elizabethan accent. A rewrite man could “make the words jump like trout”. Others could hardly write at all but were devoted to “truth in all its complexity”. The team “became like family” in what was “probably the most joyous period of my life”.

Washington was a Black-majority city but when Bernstein joined the paper it had no African American reporters (though that changed before he left) and few women in senior ranks. The media was far from immune to the racism and sexism of the period. Looking back now, does Bernstein’s infectious nostalgia therefore come with ambivalence?

“Yes,” he says, describing the Star as “a sea of white faces”, one of whom liked to boast that his family had owned four slaves. “The Washington Post was infinitely better about hiring Black reporters. It had done it going back to the late 50s. We were very late at the Star.”

Recalling several women who were leading lights at the paper, including columnist Mary McGrory, Bernstein adds: “It was not quite the sexist wasteland that you might conjure. Were there a few single women who were very beautiful and the object of a certain amount of lust? Yeah. The sexism of the day was the sexism of the day.

“But was it some kind of pit of offensive sexism? No, and the regard for the women reporters that I’m talking about was huge as colleagues very much as capable as the men. Harriet Griffiths had come on during the war: she could write a story on deadline as well as any rewrite man.”

The Star was a reflection of what was still Jim Crow Washington. In Bernstein’s account the capital sometimes sounds closer to the civl war period, then just a hundred years past, than the vibrant city it is today.

“A pall cast by the civil war hung over us,” he says, recalling how the local cinema and ice cream parlour of his childhood were racially segregated. “People in this country have no idea. I went to legally segregated public schools in the capital of the United States until 1954.

“My parents took me with them to sit-ins when I was eight or nine years old to desegregate the restaurants and the lunch counters downtown. The swimming pools were drained by the recreation department when I was a kid rather than allow integration. Imagine, the recreation department in the capital! It’s unthinkable today.”

Washington was also a place of “double vision” where politicians were both ordinary neighbours and historic figures at the same time. Bernstein had only been at the Star for about six weeks when he first saw a president in the flesh: Dwight Eisenhower sinking a putt on a golf course, his hands mottled brown.

On a bitterly cold day he was sent to cover the crowd’s reaction to Kennedy’s inauguration. He chuckles now: “It is amazing that this kid got to do this stuff. Jesus.” Nothing could compete. He writes in the book: “Now that I had covered the inauguration of the president of the United States, Mr Adelman’s chemistry class interested me even less.” (He just about graduated from school but dropped out of college.)

On the day of Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, it fell to the quick-fingered Bernstein to type the story dictated over the phone by political reporter David Broder in Dallas, Texas (this being before mobile phones or laptops). Broder began: “Two priests announced outside Dallas Parkland Memorial Hospital at 1.32pm today Central Standard Time, comma, quote, The president is dead. Period. End quote. Paragraph.”

Bernstein recalls: “My hands shook so much that I misspelt hospital ‘ol’.”

Chasing History moves on to the presidency of Lyndon Johnson with its landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. Both passed with Republican support. America, it seemed, was finally reckoning with its tortured history of slavery and segregation.

Yet half a century on, Bernstein is appalled by the Trump-infused Republican party’s efforts to reverse those gains through state-level voter restriction laws. “Now we have one of the two major political parties that in the 21st century is committed to disenfranchising particularly people of colour, but also trying to disenfranchise people who might vote against them. It has become the party of voter suppression.

“That’s an astonishing turn of events. When we were kids in school, we would do get out the vote drives for our parents and it didn’t matter if you were a Republican or a Democrat. The idea was this was a right of citizenship and so it had been extended to Black people with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“When Black Lives Matter comes along, it’s because of not continuing to fulfil the promise that began in that civil rights revolution. In addition, there is a political party that is committed to stopping that movement.”

During Trump’s four-year presidency, which he covered as political analyst for CNN, Bernstein was often asked if the scandal of the day was worse than Watergate. His answer is unequivocally yes. But whereas Republicans then forced Nixon from office, Republicans now have capitulated to Trump, his “big lie” about a stolen election and his attempted coup.

“Today one of two political parties is an authoritarian party,” Bernstein comments. “You’d have to go back to the civil war to think of anything like the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6. You’d have to go back to [Confederate leader] Jefferson Davis, who was a Democrat, if you’re looking for a seditious leader of a faction of the country. Never has there been a seditious president of the United States until Donald Trump.”

The current president, Joe Biden, recently marked the first anniversary of the insurrection by remarking that the rioters “held a dagger at the throat of America and American democracy”. With Trump and his radicalised base still looming, the threat is arguably greater than ever. America is now as polarised as it was in the 1960s, perhaps even the 1860s.

Bernstein says: “Our democracy, before Trump, had ceased to be working well and for 25, 30, 35 years we were in what I’ve called ‘a cold civil war’ in this country. Trump ignited it and we’re not going to go back from this place unless there’s some great event that somehow unites this country.

“But we make mistakes as reporters to look at the country just in terms of politics and of media. This is a cultural shift of huge dimension. Whatever you say about Trump, 45, damn near 50% of the people who vote voted for him and – you look at the surveys – some 35% of people who voted for Trump believe Christianity is being taken away from them.”

He continues: “The idea that the Trump base is some narrow group of white men with guns? Bullshit. This is a huge movement including misogynistic women, including racists of every kind, but also including all kinds of educated people in cities and suburbs.

“It’s also a movement against liberalism, against what the Democratic party in their view has come to represent. It’s about race, all kinds of forces, people’s idea of what the United States ought to be. This movement embraces autocracy, authoritarianism, a peculiarly American neo-fascism which Trump represents.”

One cultural change is the demise of the American dream, the somewhat optimistic conviction that anyone could rise to the top if they worked hard enough. Bernstein reflects: “I went to work at the Washington Star in the age of the greatest meritocracy in the history of the world. That meritocracy doesn’t exist any more. Kids are having to live in their basements with their parents because of student loans.”

To come full circle to Bernstein’s memoir, another proof of decay is the fate of local news. Almost a quarter of the 9,000 US newspapers that were published 15 years ago have been snuffed out of existence by asset-stripping companies and hedge funds as well as competition from the internet. They leave behind “news deserts” that are an open invitation for online disinformation to thrive.

“You had a kind of civic cohesion. You had great debate in cities and communities and there was an openness to truth. Now I would bet that increasingly most people look for information to provide more ammunition for their already held beliefs and prejudices, aspirations, whatever it is. That’s very different and a lot of that does have to do with the collapse of institutional news.”

Bernstein, who has written biographies of Hillary Clinton and Pope John Paul II, worries that today’s reporters spend too much time Googling at their desks and not enough pounding the streets or knocking on doors.

But he is also certain that great investigative reporting is being done, including by non-profit organisations such as ProPublica, and that the media rose to the unique challenge of Trump. “The reporting on the Trump presidency is probably the greatest White House reporting done by numerous news organisations.”

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in so Woodward , who is still at the Post, and Bernstein are likely to be in high demand. Bernstein hasn’t fully rewatched All the President’s Men for a long time. And it was not his only big-screen portrayal.

Jack Nicholson played a character based on him in Heartburn, adapted from writer and film-maker Nora Ephron’s novel that fictionalised the painful breakup of her marriage to Bernstein. “It was a tough period of my life and not a period of my life I necessarily handled well,” he says.

The short marriage produced two children: Jacob, now a reporter for the New York Times, and Max, a musician who plays guitar for Taylor Swift and Miley Cyrus. “I got him a guitar when he was three and that’s all he ever wanted to do,” Bernstein says, “Like me, he dropped out of school.”

Family has more than one definition. A few hours after the interview, the indefatigable Bernstein is talking into a computer again and retelling some of the same stories, this time at a virtual event hosted by the venerable Washington bookshop Politics & Prose. The interviewer is Woodward, who compliments him: “You really had and have a writing skill that I’ve never acquired, let’s be honest.”

Someone asks if they might team up again. Woodward says, “We sure are old.” Bernstein laughs and chimes in, “We have matching tracksuits on tonight.”

For a time after Watergate, the pair drifted apart: Woodward patrician and serious, Bernstein more flamboyant, seen out on the town with glamorous women such as Bianca Jagger, Shirley MacLaine and Elizabeth Taylor. But both are now septuagenarians on their third marriages. Both are watching American politics with alarm. The bond between them is clear.

“After all this time, we’re like siblings,” Bernstein observes during his Guardian interview. “Fifty years is a long time. It’s a great friendship. Over the years there’ve been ins and outs but it’s been pretty amazing. Great love between the two of us.”

Chasing History is out now