Column: Eye blindness, scoliosis fail to derail Gulls’ Brogan Rafferty

Defenseman, told he would never play competitive hockey, still chasing dream in San Diego

One way to gauge the hockey ice flowing through the chilled veins of suburban Chicago kid Brogan Rafferty is to tick off neighborhood repair bills.

Start with the garage door his parents paid for in the shared driveway with another townhouse, relentlessly peppered by shots that missed the makeshift net.

Throw in a taillight, windows, some drywall …

“You name it,” Rafferty said.

Stick-related damage is not the best way to understand the bone-deep commitment to the game of the San Diego Gulls defenseman, though. To fully crawl into Rafferty’s head space and grasp his remarkable drive, scan his medical history.

At age 5 or 6, Rafferty was diagnosed with amblyopia, a condition that develops in early childhood because of issues with connections between the eye and brain. The resulting muscle imbalance is commonly known as “lazy eye.”

That left Rafferty legally blind in his right eye while playing a bruising, fast-paced sport where, according to some reports, just one in every 1,000 hockey-playing boys play even a single NHL game.

Around 11 or 12, the sideways curvature of the spine known as scoliosis began to impact Rafferty. He later was told competitive hockey was not an option, a crushing forecast for someone with an uncommon love of the game.

Thousands upon thousands of players without physical challenges stumble along the road to an NHL dream. Imagine elbowing through those incredibly long odds with not one, but two things that seem insurmountable?

To explain, Rafferty dips into the well of understatement.

“I kind of have a unique hockey story, so to say, growing up,” said Rafferty, who has logged three NHL games with Vancouver while knocking on the rink door of a shot with the Ducks. “When I was 16, 17, if you put $1 on me to play an NHL game, you’d probably be a millionaire — it’s that unlikely.

“I just loved hockey so much.”

‘It wasn’t a huge deal’

When Rafferty’s grandmother first asked questions about one of his eyes, he struggled to make sense of it. Nothing seemed out of sorts. Other kids his age wore glasses.

Amblyo-what?

“It wasn’t like I was born with 20-20 vision and slowly lost it, so that’s what I knew and didn’t think anything of it,” Rafferty said. “They tried to have me wear an eye patch on my good eye to help strengthen (the other eye), but I didn’t want to wear it around the house.

“But it wasn’t a huge deal. My parents did a really good job sheltering me from my eye condition.”

Contacts counteract the differences between his eyes, which becomes more profound as Rafferty explains life without them.

Everyone can relate to a trip to the optometrist.

“If I close my good eye, my right eye has trouble,” he said. “I can’t read a book or big, bold fonts right in front of my face. You know those letters on the wall at the eye doctor? If I cover the good eye, I can barely read those giant top letters, even with contacts in.

“But I don’t really know any better. It’s not like I’m thinking, ‘Geez, it’s probably my eye because I didn’t see that guy coming’ or whatever.”

Rafferty sees enough, it seems.

The 26-year-old was named to the American Hockey League’s All-Rookie and All-Star teams in 2020 with Utica. Rafferty entered the week as one of just three Gulls to play in every game this season.

Go ahead and try to keep him off the ice. Plenty, from coaches to medical specialists, have tried.

Body-checking excuses

One summer in West Dundee, a village about 40 miles northwest of Chicago, Rafferty found himself in an awkward position during a game. His feet pointed outwardly, at a 90-degree angle, as his body twisted the opposite way.

He immediately crumpled.

“I went right down to the ice,” he said. “I was trying to make a play and my back acted up on me. Pretty bad spasms. I went to the hospital and the whole nine yards. I was told I probably wouldn’t be able to play hockey at a competitive level.”

Rafferty decided to flush those thoughts.

“I loved the game of hockey so much, that I didn’t think about all of that,” he said. “I didn’t want to let go of it.”

Though Rafferty avoided surgery, he worked tirelessly to build up muscle to support his spine. That diminished the times it slipped out of place or flared up. He learned how to play around and through it.

“Once a year in the summer, I experience some sharp back pain from heavy lifting, intense skating or working out when my body’s not used to it,” he said. “Unless my back’s really hurting during the season, I don’t really notice it on the ice.

“It might flare up a little, but I can still play and skate. I take a couple Advils, go out and do my best. I’ve gotten to a place where I know how to deal with it.”

The spine? The eye?

Just two interesting notes in his hockey-playing biography.

“I don’t use either of them as excuses,” Rafferty said.

That’s just not his thing.

Asked to think of a title for a book written about his uncommon hockey path, Rafferty paused.

“Hmmm. I would have to say, ‘The Underdog who Never Lost Hope,’ ” he said. “That’s pretty good, right?”

Damn good, actually.

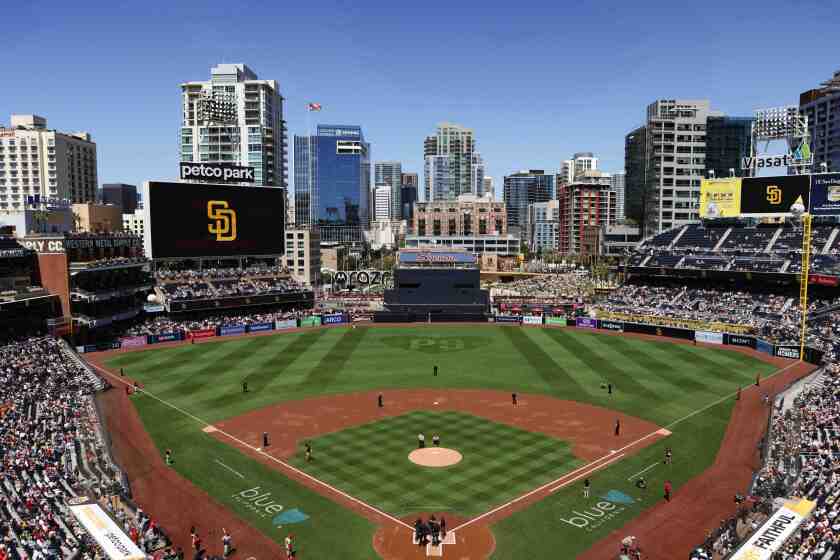

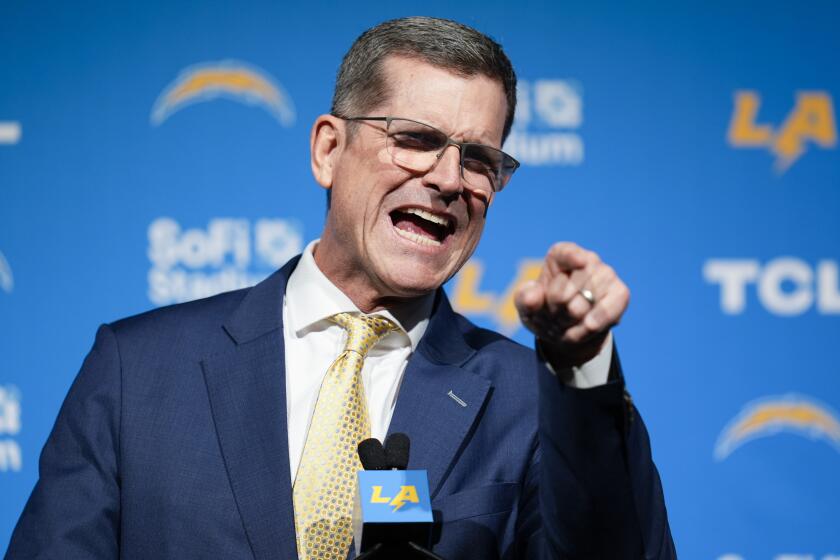

Sign up for U-T Sports daily newsletter

The latest Padres, Chargers and Aztecs headlines along with the other top San Diego sports stories every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.