Fleet Street, Friday

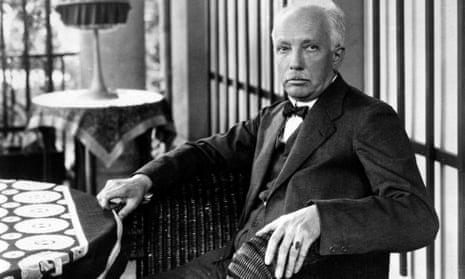

Dr Richard Strauss has arrived in London from America. It is the first time that he has visited these countries since the war. In an interview with a London representative of the Manchester Guardian, he said that his American tour had been extensive and enjoyable. He had not been troubled by any persistence of anti-German feeling, and there was a very large American public that was determined to have good music.

It was the same, he said, in Austria and Germany. Fatigue and despair created by the past terrible years had not reacted adversely on the arts. All countries lost promising musicians, but music was not affected. If there was any alteration it was towards a greater enthusiasm for music, and, indeed, for all the arts. There were fine audiences, despite the poverty, and they liked experiment and novelty, but not too much of it. There was plenty of good composition going on in Germany and Austria, both operatic and general. He mentioned the names of Pfitzner, Schreker, Korngold, and Reznicek, as men doing interesting work for opera, and said there was also a fine composer in Hausegger, but he did not attempt opera.

Dr Strauss did not wish to enter into criticism of modern musical men and movements. “One gets so easily misunderstood.” What struck him most was the rigid determination of central Europe to keep its music. In many cases that was all that was left to them, and they were eager to hold it fast. “In Vienna,” as he put it tersely, “we have hunger – and art. It is because we have lost so much that we cling so keenly to what can be retained – our art. This must survive.” It was a way to joy.

In Vienna the city, despite the parlous state of its finances, had never ceased to give a generous subvention to opera. The same was true of the German cities. The result was that seats could still be offered at popular prices for the very best music and singing that the city or country had to offer.

He could only give the figures of four months ago for the State Opera at Vienna of which he is director. There, a good seat cost 400 kronen, but he thought that it must have been raised since then. But they always made a point of keeping plenty of extremely cheap places available for the poorest people, and there was a very general desire among the workers to make use of these opportunities.

Kindly ideas of Manchester

It was a terribly hard time for the artists, and even with the aid of the public subventions it was no easier for them than for the rest of the Viennese to achieve a reasonable standard of living. But those who could took occasional working tours to Switzerland or Spain, or further afield, in order that they might make money where money meant something and then return with the exchange in favour of their savings and so keep going on with their work.

Asked whether he thought that music could really help to break down national barriers and build up friendship and understanding, Dr Strauss would not commit himself to more than hope. “Hunger and art do pull men together.” He has had invitations since the war to visit Italy and he hopes to go there later on. But the time, unfortunately, has not yet arrived for German art to be appreciated in France.

Dr Strauss has kindly ideas of Manchester, and mentioned with admiration the Hallé Orchestra, which Hans Richter formerly conducted. In present English music he has the warmest feeling for Elgar.

One leaves Dr Strauss with the impression of a kindly seriousness and a broad, equable personality. When he talks in his limited English he does not feel for his words with the impatient petulance of the man who must put out his ideas as the quick thought flows, but with the loving care of a philosopher who thinks that every phrase should be sifted and sifted again.