This week In the Hot Seat with Larry LeBlanc: Cameron Crowe, writer, director, journalist.

The writings and films of Cameron Crowe give us a fascinating, fly-on-the-wall account of life in the latest rock and roll age.

Today based in Los Angeles, Crowe held the core music audience of Rolling Stone magazine in wonderment throughout the ‘70s; starting when he was 15, and then as a contributing editor, and later as an associate editor.

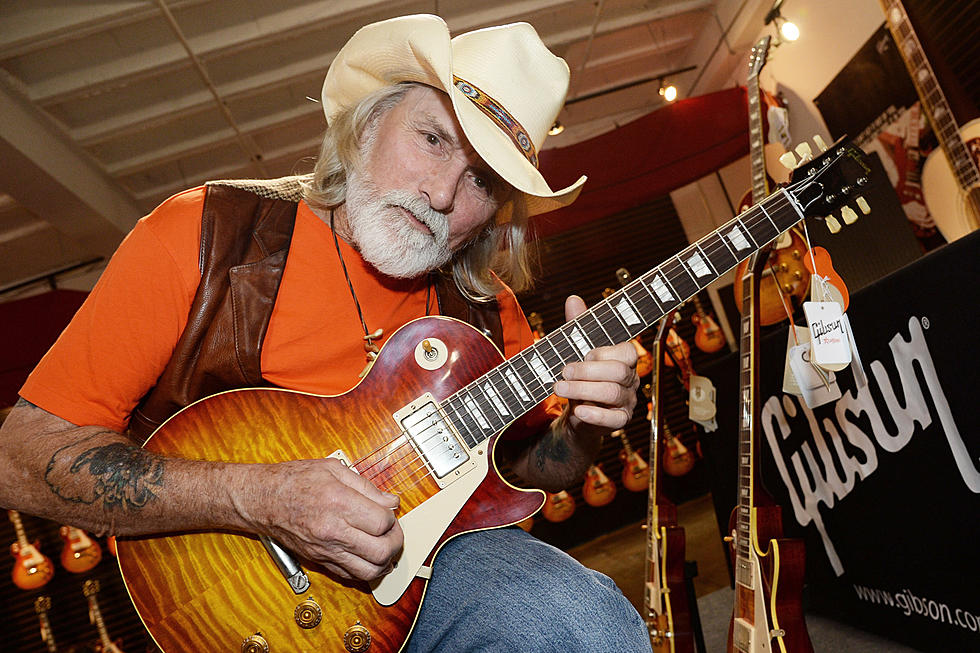

With unbridled enthusiasm, he profiled such leading music figures as the Allman Brothers Band, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Eric Clapton, Jackson Browne, the Eagles, Rod Stewart, Peter Frampton, Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, Fleetwood Mac, and many others.

A mind-boggling collection of 276 pieces that chronicle his 40 years of writing for such publications as the San Diego Door, Rolling Stone, L.A. Times, Creem, Newsweek, and the New York Times can be found on his website: https://www.theuncool.com

In 1979, using his youthful looks to disguise himself as a high school senior for a year to research a book on teen life, Crowe wrote “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” Universal Pictures optioned the book while it was still in galley form, and signed Crowe to write the screenplay for the film, released in the summer of 1982, and directed by Amy Heckerling.

Later, Crowe wrote and directed another high school tale, “Say Anything…” followed by “Singles,” centered on Gen X’ers in Seattle’s burgeoning grunge music scene.

Then came the enormous success of his 1996 film “Jerry Maguire.” The film was nominated for 5 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and Best Actor for Tom Cruise, with Cuba Gooding Jr. winning for Best Supporting Actor. The film, and a three-year deal with DreamWorks, gave Crowed the clout to make his most personal film of his career, “Almost Famous,” released in 2000, about his experiences working for Rolling Stone.

Other Crowe films over the years include: “Vanilla Sky” (2001), “Elizabethtown (2005),” “We Bought a Zoo” (2011), and “Aloha” (2015).

Crowe’s television series, “Roadies,” in 2016 for Showtime, chronicled life on the road with the Staton-House Band, was canceled after one season.

Also, Crowe has penned books of his films “Fast Times At Ridgemont High,” “Jerry Maguire,” “Almost Famous,” “Vanilla Sky,” and “Elizabethtown,” as well as “Bob Marley and the Golden Age of Reggae.” with Jeff Walker, and photojournalist. Kim Gottlieb-Walker, and “Conversations With Wilder,” a collection of interviews with legendary film director Billy Wilder.

Lately, Crowe has been working on the Broadway adaptation of “Almost Famous” as well as on his on his memoirs and assisting Joni Mitchell with her archival Rhino Record releases.

You have been working a great deal with Joni Mitchell of late.

We are doing these “Archives” (box sets). It is so much fun. She would always say, “Well, there are no outtakes. There’s nothing that wasn’t released that is worthy of being released. I’ve got nothing. These records are what they are.” Of course, Elliot (friend and ex-manager Elliot Roberts) before he died (on June 21st, 2019)–which is a tough thing even to acknowledge, such a great guy–but Elliot was like, “Joni, you have 60 songs that you wrote before the first album. You have an enormous amount of live material. You have the early versions of these songs. You have to put them out.”

She had finally decided to embrace her early work, all of the outtakes, all of the nooks and crannies of her body of work before Elliot passed away. So kind of in honor of Elliot, and also just her curating her life and finding the time to look back over everything, she has approved the releases, and along with Patrick Milligan (director of A&R, Rhino Entertainment), they have all of this stuff out of her deep archive of unreleased material.

(“Archives Volume 2: The Reprise Years (1968-1971),“ released on Nov. 12th, 2021 by Rhino Records in an effort to sort through 6 decades of Joni Mitchell’s musical catalog, is the follow-up to 2020’s early days era of Volume 1,” and documents Joni’s journey as a songwriter, artist, and performer. The 5 disc set includes archived material recorded in the years between the release of Mitchell’s debut album, “Song to a Seagull” (1968), and her fourth studio album, “Blue” (1971).

Where were the tapes?

They have all been floating around, Larry. She had a lot of it, and who had a lot of it was (photographer, musician, record producer, and archivist) Joel Bernstein who is kind of her archivist. Over the years, Joni would give him her tapes, and say “You know what to do with this.” What he knew to do was keep them, log them, treasure them, protect them. And what they have done is brought all this stuff together into one place, and now they are releasing it. Each volume is about three or four records

You credit cinematographer John Toll with the authentic ‘70s feel of “Almost Famous”– turning hotel rooms, and buses into emotional landscapes from images you ripped out of magazines and photo books for years–but Joel’s photography was a key inspiration for the film’s naturalistic look in which many scenes were precise re-creations of his photographs.

Neal Preston’s too.

What is the process of working with Joni?

We get together every week, and we work our way through her music which is like dream come true. Last night, we got into “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” (1975) and that was really fun.

“The Hissing of Summer Lawns,” and “Mingus” (1979) are my favorite Joni albums. “Mingus” has been so overlooked and underestimated.

Yes, I know. Yet another portal to the next phase of her career. And I know that this is true. Nobody wanted her to make that record.

How did you first get introduced to Joni’s music?

I was a huge fan of “Both Sides Now,” the Judy Collins’ recording (“Wildflowers,” 1967) was something that cut across the “No rock allowed” in our house. I was just fascinated to get “Clouds” (Joni’s 2nd LP in 1969), and learn songs like “I Don’t Know Where I Stand,” or “Chelsea Morning.” I loved her artful way. So when our family favorite, (talk show host) Dick Cavett had Joni Mitchell on (his program) a couple of times, she was kind of a portal for rock wafting into our house in some form because she was the person who wrote “Both Sides Now,” and like, “Wow, look at her, she is just on her way as a songwriter. She’s amazing.”

Then one day coming home from summer school which my mom made me go to—“You will be happy later when you go partying with your friends that you’ve gotten out of a semester of school.” So walking home sadly on a summer day, I passed this record store near the beach, and the summer school that I was going to, and there was “Blue,” the new Joni Mitchell record (released in 1971) in the store window. I didn’t realize at the time, or I did, and it didn’t matter, that it was such a cool record store, but they hadn’t figured out to put curtains on the window and (the sun) was warping all of the records on display. This copy of “Blue” that I came home with that day had a wobble in it on the song “California” that I still hear now. But that was when everything galvanized for me. As a little guy, I listened to “Blue,” and I just thought that this was a romantic vision that I hoped I’d step into someday, all of this glorious pain and romance. I immediately wanted to write about it, Larry, like you. You were able to do it before any of us when Joni was doing no interviews, and I seized it on your interview with her right around the “Blue” period.

I interviewed Joni at the Mariposa Folk Festival on Central Island in Toronto in July 1970, and Rolling Stone published my article “Joni Takes A Break” in its March 4th, 1971 issue.

The next day I took Joni. James Taylor and publicist Richard Flohil’s daughter in a paddleboat ride around the island’s lagoon.

Joni had played Mariposa Folk 1966, ’67, ’68, ’69, and would play it again in ’72.

You got her at that pivotal time where she had just got back from Greece, right?

Yes. her self exile from the pop music scene. Earlier that year, she had made the surprise announcement of a self-imposed retirement and canceled two important gigs at New York’s Carnegie Hall; and Constitution Hall in Washington. She took a vacation instead, traveling to Greece, Spain, France, and from Jamaica to Panama, through the canal.

She told me that she’d become frightened by celebrity, uneasy of the photographers scrambling around her, and crowds fawning on her at every turn, wanting something, wanting to touch her. She talked about how the “fame game” was not for her.

In a Grover Lewis (Rolling Stone) profile of (former manager/label owner) David Geffen, he said, “Of all of the stars that I’ve ever known or worked with Joni Mitchell was the only star that wanted to be normal.”

Joni’s mother Myrtle told me some funny stories of Joni bringing David Geffen, and also a strung-out James Taylor, home with her to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Boy, Myrtle Anderson, and David Geffen. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall for that.

Joni was among the recipients of this year’s Kennedy Center Honors, and the televised ceremony which took place on Dec. 5th, 2021. She is set to be honored again as the 2022 MusiCares Person of the Year that will happen two nights before the 64th Annual Grammy Awards, likely in April. Among those expected to honor her are Brandi Carlile, Graham Nash, Herbie Hancock, James Taylor, Leon Bridges, Pentatonix, Black Pumas, Jon Batiste, Maggie Rogers and Mickey Guyton

What is so compelling about Joni, beyond the glorious singer/songwriter era of the ‘70s that also includes James Taylor, Jackson Brown, Paul Simon, Laura Nyro, Gordon Lightfoot, Leonard Cohen, and others? That still resonates today?

Because of authenticity, and she’s probably one of the only people that wasn’t branded forever with what she did that became successful early on. It is really hard to find an artist that doesn’t freeze in the exact place that they got their success, It’s ironic because usually the great success—look at Bruce Springsteen—comes on the next record after they have hit someplace that is truly beautiful. and authentic, and real.

Whereas Joni became successful for the singer/songwriter stuff, but she kept going. She said, “Well, I want to make great records now. I just don’t want to be a girl with a guitar. Now I want to work with a band.” Then she gets a band together, and she is producing these records herself with Henry Lewy, and she got a band there of these great jazz guys.

Henry collaborated with Joni on the engineering and production of “Clouds,” “Ladies of the Canyon,” “Blue, “Court and Spark,” “The Hissing of Summer Lawns,” “Hejira,” and “Wild Things Run Fast.”

The jazz players were saxophonist Tom Scott and the L.A. Express with drummer John Guerin, bassist Max Bennett, guitarists Larry Carlton or Robben Ford, and the Crusader’s pianist, Joe Sample, played on “Court and Spark,” “The Hissing of Summer Lawns,” and the live album “Miles of Aisles.”

Tom Scott, right. The band is there, she’s speaking to them in colors. She is saying, “I’m looking for more of a purple thing here.” Or “Here’s the direction. The lyrics don’t step on them. Let’s go.” She is not playing the shrinking violet playing “Chelsea Morning” within 18 months, she keeps going. I love the story of the restless creativity of Joni. James Taylor is somebody of equal authenticity in the early part of his career, and he was happy to hang in that gear, and he still is there, and it’s beautiful.

What James has done is refine his music.

Exactly.

James keeps refining his music while getting better and better at what he does.

That is really well observed. That is kind of like a Norman Rockwell thing, right?

You have been writing your memoirs. How deep are you into them?

Pretty deep. I started with the early times in San Diego. So I am up to ’73 or ’74.

Have you been digging out your day timers that read, “Jimmy Page on the phone coming up, and Bonnie Raitt on page four, here I go?”

Yeah, that kind of stuff. San Diego was an amazing place to be at that point. The underground press had popped up in Los Angles with the L.A. Free Press…

Also called “The Freep,” the first, and certainly the largest, of the underground newspapers of the 1960s.

So San Diego had gotten this underground paper called The Door.

Originally named Good Morning Teaspoon which covered politics and counterculture through the late ’60s and ’70s. That’s where Lester Bangs was working.

He was still writing record reviews for The Door. My sister got me into a meeting at this kind of commune newspaper building where people were smoking pot, and talking about the revolution, and there were free promotional records leaning against the wall. Someone said, “Somebody has to review these records. We are all interested in politics. Nobody wants to write about music.” I was like, “I WILL WRITE ABOUT MUSIC FOR YOU.”

Cameron, the primary reasons we both became music journalists at the age of 15, was to have an identity at high school and to get free records.

Free records, it’s not more romantic than that. It’s the identity in high school, and free records. I just couldn’t believe the idea of free records. I even liked that they (the labels) punched a hole, and you couldn’t resell them. I liked the sticker that said, “For Promotional Purposes, Not For Sale.” It felt like a badge of honor to have a record like that. I went home from that first meeting with Carole King’s “Music,” Rita Coolidge’s “Nice Feelin,’” and Todd Rundgren’s “Something/Anything.”

Ageism is a fact of life for rock artists, but also for rock journalists. This music wasn’t supposed to last forever. You must have gone through that age bias yourself at some point.

I don’t know. A little bit.

C’mon, as director John Hughes did with “Sixteen Candles,” “The Breakfast Club,” “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” and “Pretty in Pink, you were making adolescent films, and you weren’t a youth anymore. You are now 64 so….you are now almost a senior citizen, pal.

Yeah, it is something that you gotta face, but a lot of being fans the way we are Larry, I think that we have people that we look up to. and sometimes the third act pieces of music or books, sometimes that later period stuff is marinating in a lot of goodness, and you put something out like “Blood On The Tracks.” Bob Dylan was far younger, but he’d already lived a couple of lives when he was the age we are talking about when he did “Blood On The Tracks.” Nobody would have faulted him for then saying, “I’m done.”

Bob Dylan began recording “Blood On The Tracks” in New York City in September 1974. That December, shortly before Columbia was due to release the album, he abruptly re-recorded much of the material in a studio in Minneapolis. So he would have been 38 when the album was recorded.

That was the ushering in of his third act and that was thrilling. So I kind of look at artists like that, (Hollywood’s legendary and famously elusive director) Billy Wilder did great work later in life. I was lucky enough to write about Billy Wilder and study him (for the book “Conversations with Wilder” in 2001) Here was his secret, curiosity. This was the most energetic, serious, brilliant, funny guy I’d ever known, and still have ever known, and he was 93.

Billy Wilder died in 2002 at the age of 95. His gravestone’s epitaph in Westwood Village, California, in a nod to the legendary last lines in “Some Like It Hot,” his classic 1959 movie, reads “I’m A Writer But Then Nobody’s Perfect.”

That is the kind of spirit that I want to lock into.

Too many people in entertainment freeze themselves in the past. They refuse to move on or learn about improved methodology or new technology. So many have remained stuck in the ‘70s or ‘80s, saying, “This is when the best music was.” I’m like, “Are you kidding? Have you heard Yebba, Amber Mark, or Bruiser Wolf?

You have that curiosity or we wouldn’t have had this conversation. It is either in you or it’s not. Look at Tom Petty. Listening to his radio shows (44 episodes of his acclaimed “Buried Treasure” radio show). Sadly, we lost him way too early (in 2017). That radio show, that is no oldster saying, “I’m about to retire. That is a guy that is still hungry. That is who you want to be. That is what keeps you young and that is what keeps you exploring. You know that.

Considering the fact that you come from journalism background, it must be somewhat strange for you to be interviewed.

I am much happier being the interviewer. Even talking with you. I am much happier being the one asking the questions because I want to know about you. I just love the conversational style that you have which is not an interrogation. You bring the people that you are interviewing out of a “Us against each other” kind of mindset. I always feel that you are the clear-eyed friend on the same side of the table as them who has to hear the truth, get the truth, and write the truth. And that’s the best.

Still, I bet you’ve written a profile article, and its subject came back to you, and said, “Cameron, I thought we were friends.”

Yep. It definitely happened, but most of the time since I was 17, I think that I realized that the graciousness and good manners and the attitude that somebody you are writing about is centered on the hope that you are going to write something good about them. So sometimes when it comes out, and it’s not a hosanna, there are tumbleweeds if you ever try to get ahold of the person or need them for something again. But that’s part of it. My favorite guy, my favorite interviewer–I’d love to hear what kind of your choices would be—but I always loved Dick Cavett.

Dick Cavett may have been the last of the great sit-down, fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants TV talkers, but Merv Griffin was a master of the conversational style as well; though Merv was more show biz in his presentation.

So true.

(From 1968 to 1975, ABC-TV The Dick Cavett Show” was an intrinsic part of the cultural—and countercultural—milieu. Movie stars, rock stars, literary giants, authors, politicians and, athletes appeared on his show with nary a moment of self-promotion.

Unlike other talk shows of the period, Cavett’s featured rock artists including David Bowie, John Lennon, and Yoko Ono, Janis Joplin, Ray Charles, along with such entertainment figures as Alfred Hitchcock, Fred Astaire, Woody Allen, Gloria Swanson, Jerry Lewis, Lucille Ball, Zero Mostel, Bob Hope, Orson Welles, Noël Coward, Laurence Olivier, Judy Garland, Bette Davis, and Katharine Hepburn (who appeared without an audience).

Cavett had the ability to exclaim, “I’m going to ask a really dumb question because I really want to know.”

Dick Cavett was a conversationalist and that is how you are going to get Katherine Hepburn to tell you her best story. That is how you are going to get Groucho Marx on your show. You are not going to get thrown against the wall, and asked for answers like a cop. You are going to have a living room conversation with someone who doesn’t do it (interviews) that much. That is my favorite way to approach it.

One of my journalism heroes was the late Grover Lewis whom you mentioned in a recent communication to me. Appearing mostly in magazines like Rolling Stone and New West, Grover wrote informative articles of such giant personalities as Robert Mitchum and Lightnin’ Hopkins. His most memorable stories recorded significant cultural events, including the filming of “The Last Picture Show,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “The Getaway,” and “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” as well as an Allman Brothers Band tour, and the Altamont Speedway Free Festival held in 1969.

The Rolling Stone article that Grover did on Peter Bogdanovich’s coming-of-age drama film, “The Last Picture Show,” put you directly on its set in author Larry McMurtry’s small hometown of Archer City, located in north-central Texas. You were there for the blow-by-blow account between the director, crew, and actors on the set.

Yeah he would embed himself in the film sets that he would write about. and get amazing stuff.

Many of us from the ‘70s era of music writing are the New Journalism offspring of author Tom Wolfe, and also Paul Williams, founder of Crawdaddy magazine.

Totally.

In that, we wanted to capture the essence of a person’s life in a feature article. That moment in time on that day. That comes with some good and bad conduct. I never have been drawn to journalists who just tear their subjects apart or who act like they are bigger than subjects or on the same footing. Those traits aren’t helpful in capturing a person.

That is really well said. I think also that kind of a journalist is a center stager. They can’t bear to give the stage over to the person they are interviewing. They want that person to be reacting to them. Once you play that ball game, you better be Lester Bangs or Hunter S. Thompson or I don’t want to hear what you want to say because I didn’t buy your record. I didn’t go to your film, and I didn’t read your books. I’m trying to get you to put me in the front row so I can learn more about the person that I am interested in, forgive me, but not you. That’s what a lot of these guys…I don’t know, there’s room for everybody, but particularly in the time of Grover Lewis, I liked that it was verité. Puts you right there.

Sadly, with both Hunter S. Thompson and Lester Bangs, their colorful cult personalities somewhat overshadowed their attributes. Hunter had first been a fine sports journalist, and then an unequalled social writer, and Lester was a brilliant writer.

No question. No question.

The journalists that have tried to emulate or imitate Hunter or Lester never got it right.

That’s really true. That’s what lasts which is the authentic presence, and voice that those guys had. And you can always tell. It’s in your gut really, when you have a watered down version of something; that you can often tell that there is a more potent brew around the corner, and they are imitating.

Among other rock journalists with original voices from that era in my opinion would also be Richard Goldstein, Lenny Kaye, Michael Lydon, Nick Tosches, Nick Kent, Jon Landau, John Rockwell, Bud Scoppa, Dave Marsh, Ben Fong-Torres, and Greil Marcus.

As we talked about recently, the writers that shaped me—and probably you as well– were not the rock journalists, but the likes of Joe Klein, Nora Ephron, Joe Eszterhas, Pauline Kael, Jimmy Breslin, P.J. O’Rourke, Tom Wolfe, and Joan Didion. And Gay Talese, if only for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” for the April 1966 issue of Esquire (April 1966.)

As you were trying to dig deeper in your stories at Rolling Stone, Jann Wenner gave you a copy of Joan Didion’s 1968 essay book, “Slouching Toward Bethlehem,” and told you, ‘This is the future of what you’re doing now if you can hook in to a more thoughtful, more soulful place.” Then you read Joan’s profile on Jim Morrison, and you recognized that it was about so much more than just Jim Morrison.

At the same time, music journalists then, including you and I, were often embedded with bands on tours or in the studio. You were on the road with Led Zeppelin for three weeks in 1975. You wouldn’t get that kind of access or time today with a band.

No, you wouldn’t.

Being on the road with Led Zeppelin or with any other band, there are things that you see that you can never report on. You have to filter what you can or can’t write about.

Yeah. It wasn’t like there was somebody was there with a non-disclosure agreement to say, “This is what you write about, and here is what you don’t write about.” In terms of Led Zeppelin, obviously, they were not enamored with the idea of rock journalism.

When you interviewed Led Zeppelin for what became Rolling Stone’s March 13, 1975 cover story, titled “The Durable Led Zeppelin,” the members weren’t enamored with the publication either. They, in fact, carried around John Mendelsohn’s scathing review of their debut album for years. They had memorized it word for word.

(John Mendelsohn’s review read: “The latest of the British blues groups so conceived offers little that its twin, the Jeff Beck Group, didn’t say as well or better three months ago, and the excesses of the Beck group’s ‘Truth’ album (most notably its self-indulgence and restrictedness), are fully in evidence on Led Zeppelin’s debut album. Jimmy Page, around whom the Zeppelin revolves, is, admittedly, an extraordinarily proficient blues guitarist and explorer of his instrument’s electronic capabilities. Unfortunately, he is also a very limited producer and a writer of weak, unimaginative songs, and the Zeppelin album suffers from his having both produced it and written most of it (alone or in combination with his accomplices in the group).”

You later wrote of your Led Zeppelin cover story, “Very very proud of this one. The quest to land Rolling Stone’s first interview with Led Zeppelin was a rough one. The magazine had been tough on the band. Guitarist Jimmy Page vowed never to talk with them. While touring with the band for the Los Angeles Times, I attempted to talk them into speaking with me for Rolling Stone too. One by one they agreed, except for Page. I stayed on the road for three weeks, red-eyed from no sleep, until he finally relented… out of sympathy, I think. My mother was about ready to call the police to drag me home. Needless to say, the incident shows up in a slightly different form in ‘Almost Famous.’”

Is it true Led Zeppelin members carried around John Mendelsohn’s Rolling Stone review of their debut LP?

Along with their copies of the Guess Who albums that they played on vinyl on the road, my friend.

The Guess Who?

Oh yeah. Robert Plant loved the Guess Who. That’s the fun stuff. When you get your interview, and you are there, and Jimmy Page pulls out a Bob Marley record “Burnin’” (the 6th album by Bob Marley and the Wailers, released in 1973) and says, “This is the guy. Let’s listen to this guy.”

And you realize we are all music geeks. Whatever anybody says, I think that anybody who picked up a guitar or learned to play a piano or whatever just to get drugs and sex, they weren’t around very long. It’s the people who craved blues records or their favorite artists, and studied their songs or couldn’t finish a drive because a record came on the radio that was so riveting that they had to pull over. That’s the stuff that drives most of these bands, the great ones, I think.

The deal with Led Zeppelin was that I remember being a young guy, and they were like, “Hey, good for you. You get us. Somebody gave you a job to write how you feel in a publication. Come with us.” That was the spirit of them letting me and Neal Preston tour with them.

It wasn’t quite that easy to get them to agree to a front cover Rolling Stone story. Joe Walsh, who was on the road with Led Zeppelin at the time, had to talk Jimmy into giving you a shot. Walsh said, “You should trust this kid, c’mon. He loves your band, he wants to write about you. Let him be on the cover with this story.”

Well yes, that’s the cover of Rolling Stone. When they took me on the road, it was “You write for the other publications that you work for and do whatever you are going to do. For Circus magazine or whatever. But you are not going to do this for Rolling Stone.”

You told them you were covering the band for the Los Angeles Times.

Well, it was for the Los Angeles Times. I did that coverage for the L.A. Times, and then I stayed on thanks to (Rolling Stone writer and editor) Ben Fong-Torres, to try to convince them to do the Rolling Stone cover too. And then they finally acquiesced. But it was Joe Walsh that helped wrangle them and get them to pose (for the cover).

You were at Rolling Stone for 6 years. You arrived as many of the veteran editors and journalists there, as with other American and British underground and rock publications, were now in their 30s.

Telling you that you had arrived too late.

The beginnings of heavy metal and disco were evident, and there were a lot of cynical, and skeptical people at Rolling Stone, and throughout the music industry at the time. Many journalists, managers, and label personnel were beginning to struggle with the journey of growing up and leaving home (leaving their jobs).

It’s true.

Rolling Stone has played such a role in the history of our times, socially and politically, and culturally, but the magazine by then was shifting away from its 1967 Summer of Love origins.

It’s true, but they did know that their advertising revenue was going to come from music because it still largely was a music magazine. Patty Hearst isn’t going to pay for ads.

Record companies were still the primary source of Rolling Stone’s advertising base?

Yes. So, they knew that somebody had to write about Jethro Tull. They knew someone had to suck it up and write about Deep Purple. I was like, “Suck it up, and write about Deep Purple? I love Deep Purple.” What do you write about Deep Purple? “There’s the beauty of “Machine Head’” (1972). They were like, “Let’s see what kind of copy we get from this kid. At least, we will have Humble Pie in the magazine, and A&M Records will buy their ad.” That was the cynical side of them giving me a platform.

Editors at Rolling Stone told you, “You should write about somebody you don’t like. Write about somebody whose music you don’t care about. Test yourself.” And instead, you write about Peter Frampton, the nice guy of rock.

Yeah, it’s true, but Peter Frampton was legitimately a good story. He was going through the stratosphere of what rock was becoming in terms of a global enterprise. He got panned with being the poster boy. I think that Peter Frampton became the poster child for marketing, for outright marketing in rock. They kind of decided that he was going to be a shirtless God.

Many rock journalists then so hated dealing with his manager Dee Anthony who also handled Humble Pie, Jethro Tull, Joe Cocker, Gary Wright, King Crimson, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and who was reputed to have links with the Genovese crime family in New York City.

That is true.

Fred Goodman recorded Dee Anthony’s three rules of success in his 1997 book “Mansion on the Hill”: “1) Get the money”; 2) “Remember to get the money”; and 3) Don’t forget to always remember to get the money.”

I first came across Peter Frampton in the Herd which had three UK Top 20 hits in the late 1960s, “From the Underworld, “Paradise Lost,” and “I Don’t Want Our Loving to Die,” before Peter left in 1968 to form Humble Pie with Steve Marriott.

I have to check out the Herd

Peter Frampton was 16 when he was in the Herd, and he was tagged “The Face of ’68” by UK teen magazine Rave. You should talk to Sharon Osbourne. She was at the Italia Conti Academy, Britain’s first performing arts academy, with Steve Marriott who was a child actor.

Oh, wow.

As Steve was forming the Small Faces, Sharon introduced him to her father Don Arden who became the band’s manager.

Yeah, man.

Sharon is incredibly bright and very funny.

She is funny, and a brilliant woman.

More than two decades after “Almost Famous” hit theaters in the fall of 2000, it has passed beyond being a heartfelt, nostalgic cult classic to becoming one of the most beloved movies of our time.

It’s hard to imagine rock and roll touring without conjuring up “Almost Famous.”

For grizzled, first-generation bands on the road, and kids growing up with music in post-war America, there simply is no clearer symbol of achievement than touring as a teenaged San Diego reporter named William Miller on the road in 1973 with an emerging fictitious Midwest rock band, Stillwater (a bastard child of the Allman Brothers Band) for Rolling Stone. As he falls under their spell, he interacts with the band’s followers, including Penny Lane.

“Almost Famous,” despite critical acclaim and 4 Oscar nominations—and you winning for Best Original Screenplay, and the film winning two Golden Globe Awards, for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy and Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture for Kate Hudson as Penny Lane, fizzled at the box office. outgunned by the release of the “Director’s Cut” of “The Exorcist,” the supernatural horror film directed by William Friedkin.

The “Exorcist” re-release, subjected to editorial tinkering–no doubt to justify the advertising blurb, “The version you’ve never seen, just buried “Almost Famous.” But over the years, word-of-mouth momentum of the film prevailed.

It’s been a word-of-mouth journey from the very beginning. This is the dream that home streaming video, and all of the other avenues, can help people see a movie that they hear about. Yes, it was a bust in the theater. We got creamed by the re-release of “The Exorcist.” It was like, “Your lovingly crafted movie about 1973 will come out on the same day that a (horror) movie from 1973 is re-released and crushes you.” That’s what happened. But slowly, but surely people kept watching it on video, and it became a hit on video, and people kept watching it even more

Then we put a musical together based on “Almost Famous.” It’s got a lot of original music written by (two-time Tony Award winner) Tom Kitt (“Next to Normal,” “American Idiot,” and “The SpongeBob Musical”) and Lia Vollack is producing, and we and we have a great, super-funny and very disciplined director in Jeremy Herrin (“Noises Off,” “Wolf Hall,” and National Theatre Live’s “All My Sons.”). I met him, we immediately spun off into how much we love music, and I told Lia, “this is the guy. We need look no further.”

Jeremy helped me navigate the bumpy path of writing musical-theatre. Basically, it’s “people sing their private thoughts” which was a fun thing to traffic in, once you get the hang of it. I thought (WRITER/PRODUCER) Diablo Cody did a great job on “Jagged Little Pill.” She was actually the one I called and asked her about Tom Kitt. She said, “he’s the best. You won’t be sorry.” We became good friends, good work partners.

So we put on “Almost Famous,” the musical in San Diego, my old hometown, right before the pandemic (at the Old Globe Theater in San Diego in 2019), and it was sold out every night. We had a blast. We had standing ovations. It was such a personal experience because all of the “Almost Famous” fans came out or traveled to see the show. It just made me appreciate the fact of you and me loving the music that we love, and that people choose what moves them as well. You don’t need a lot of flashy marketing for that to happen. You just have to make it available somehow, and word-of-mouth sometimes can be your best friend.

The show is not a retread of the movie, it’s a jam in the spirit of the movie, and gives you that same feeling of freedom and loving music. So, I thank Jeremy and Tom and Lia and the beautiful cast for that experience. I was worried heading into it because I’d never done a sequel or a continuation and didn’t want to mess with something that we were lucky to catch a little lightening in a bottle with years earlier.

“Almost Famous” was slated to open on Broadway in November 2020 but was canceled due to COVID-19. Will it reach Broadway now?

It will go to Broadway in late summer or early fall of 2022.

Would you put some of the music from the film in the musical?

Keeping a few secrets here…

Anything by the Seeds?

I was just listening to the Seeds yesterday. ““Can’t Seem To Make You Mine,” c’mon. There is no Seeds but of course, we do pay homage to the Guess Who. Rob Colletti plays Lester Bangs, and he roams the audience before showtime and debates music with audience members. Look for him. You’ll find him to be a very vocal Guess Who fan.

And you just have to have “Albert Flasher” by the Guess Who.

Well, now you are talking. “Albert Flasher” is one of the great songs, one of the great Guess Who songs, but also one of the great songs. I loved interviewing Burton (Cummings).

An early draft script of “Almost Famous” was titled “Ricky Fedora,” and you wrote a role for David Bowie based on British publicist Derek Taylor who worked with the Beatles in the UK, and later in L.A. He oversaw publicity for the Byrds, the Beach Boys, the Mamas & the Papas, and Paul Revere & the Raiders, becoming the most famous rock publicist of the mid-’60s.

Wow, Larry, you know the deep tissue. That’s amazing. It began as a project called “Ricky Fedora.” It was a little bit of a Peter Frampton story, and it had a little bit of an influence of what I had seen around Eddie Vedder (Pearl Jam) when success happens a little too early maybe for what you were planning for. The cool thing about “Ricky Fedora,” is it was all an attempt to write a character for David Bowie because I loved his acting. I thought, “Well, if we write a character that is kind of a Brian Epstein, one of the early figures in rock publicity, a guy with panaché blazing his way out of the Mod period and taking you into the early ‘70s as a publicist trying to branch out into management, and there is this character called Russell De May that I had written for David Bowie. And Ricky Fedora was the artist, and he was from Bromley (in South London) like Peter Frampton (and David Bowie). Then “Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery” (1997), came out, and suddenly everybody was doing a parody of a British rock star. It was all, “Let’s smash a hotel room and be rockers.” Everything was a parody of that kind of person. So I was like, “I can’t do this. I can’t have a movie about a British rock star that is semi-serious. People are going to be waiting for the jokes.” So I flipped the whole thing inside out, lost the David Bowie character, and made the movie kind about a Grand Funk, Michigan, bubbling under Mid-Western band. That kind of broke up “Almost Famous,” and that became the movie and everything.

You obviously met David Bowie

I did. David Bowie was one of the most inviting guys when I was a young journalist. He invited me to spend 18 months around him. I was there for all of “Station to Station” (1976), the Iggy Pop demos that he did; basically up until he leaves for Berlin to save his life, I was chronicling Bowie.

You witnessed just how funny he could be.

A hilarious guy. He was driving himself around Los Angeles in a yellow VW bug.

David would stay up all night recording “Station to Station,” or doing demos with Iggy, and June Millington of Fanny. And then, in a yellow VW that he was using, he would drive you in the morning traffic to [photographer] Neal Preston’s house where you were staying in the Hollywood Hills.

It was during his lost 18 months after he left his manager (Tony Defries) when he was just careening through L.A. and making this amazing record “Station to Station.” He even invited me to watch him write a song using the cut-out method. I have it on tape. He writes a song using auto-suggestion (a form of self-induced suggestion in which individuals guide their own thoughts), and cut-out songwriting. Writing like (William S.) Burroughs. I have it all on tape. The song is called “Audience.” He invited me to participate in the demonstration of the William Burroughs “cut-out” method of writing. It is kind of an amazing little odyssey that I was able to tape because Ron Wood–who I had written about, one of the most engaging guys to interview ever. You might have met him 20 minutes earlier, and he makes you feel like you grew up together. He was the most cooperative interview ever, and his buddy was Bowie at the time. I mentioned to Ron how much I wanted to interview Bowie, “But nobody can interview Bowie because he doesn’t do interviews.” Woody was like, “He’ll be over in about 20 minutes. I’ll ask him and you will be right there.”

And he did.

(Tony Defries and David came to a settlement in 1975 between David, RCA Records, the rights management organization MainMan, and Defries who gave up David’s personal management but retained a shared control of other aspects of David’s catalog and career.)

(Emily Lazar, president/chief mastering engineer at The Lodge, worked on David Bowie’s “Heathen” (2002) and “Reality” (2003). For her “Heathen” (2002) and “Reality” (2003).

For her “In The Hot Seat” profile in 2015, I said to Emily, “You met David, He’s very funny in-person.” Her answer was:

“He’s hilarious. He’s very funny. He’s a consummate entertainer. He walks into a room, and he’s on, and he’s so engaging. He lights up a room for sure. I was laughing all the time. There’s one amazing thing that happened one day. He came in, and he had just seen Ozzy Osbourne’s reality show (“The Osbournes,” which followed the lives of the Black Sabbath singer and his family). (Ozzy’s wife) Sharon wanted Ozzy to fly out in this (bubble machine) thing to the stage. He freaked out, and he said, “I’m effing Ozzy Osbourne, the Prince of effing Darkness. Evil. Evil. What’s evil about a shitload of bubbles?” He thought it was ridiculous. That was his response. It was a very funny moment in that reality TV show because it was an Ozzy rant. It became sort of famous. That had just happened, and David came in to do his stuff. When we were working, he was telling stories. He said, “Oh my gawd have you seen this Ozzy Osbourne thing?” Then he starts imitating Ozzy. His imitation was so spot on. He was doing this imitation of Ozzy Osbourne and I’m sitting there pinching myself saying, “Okay, is this really happening? David Bowie is imitating Ozzy Osbourne in my studio trying to make me laugh. What’s going on here? This is crazy.” David is such a sweetheart.”)

Fantastic.

You know David wanted to do comedy in films, but producers and directors wanted him for “Elephant Man” type roles.

Oh wow.

(From July 1980 to January 1981, David Bowie played the part of the real-life 18th century character Joseph “John” Merrick. He portrayed Merrick in Barnard Pomerance’s 1977 play “The Elephant Man,” directed by Jack Hofsiss. It was Bowie’s only theatre role, and it was a critical and commercial success. He was widely praised for his part in the play, contorting his body and voice to convey the hideous deformities, and the humanity of Merrick.)

The long-form video of “The Jean Genie” in which David plays both the star and a helpless window cleaner trying to impress a beautiful date, is a fascinating comedic study. And there’s his role in John Landis’ 1995 black comedy thriller “Into the Night,” starring Jeff Goldblum and Michelle Pfeiffer, in which David plays an inept MI5 case officer with a band-aid on his nose throughout, showed that David was a highly talented comedian to boot.

Oh wow. He’s great with Rick Gervais in “Extras.” Unbelievable.

Gervais convinced David to play a hyperbolic version of himself in “Extras” in 2007 with him performing the hilariously brutal song, ‘Little Fat Man’ aimed at Gervais’ character Andy Millman. As a thank you to Bowie, Gervais agreed to perform at the inaugural High Line Festival in New York on May 19th, 2007 that David had curated the line-up for. David walked out onstage at in Madison Square Garden in a tuxedo, with a little harmonica, and began to sing, Chubby little loser…” And the crowd went bananas. And then he brought Gervais on. That was David’s last live show, and “Extras” was his last filmed appearance.

You are kidding me.

Music is so very central to your life, and the cornerstone of your films in which you work closely with music supervisor/soundtrack producer Danny Bramson. You two collected over 77 songs for “Almost Famous,” leading to its soundtrack being presented a 2001 Grammy Award for Best Compilation Soundtrack Album For A Motion Picture, Television Or Other Visual Media in 2001.

(Danny Bramson founded, and headed MCA Records’ subsidiary label Backstreet Records, and was executive director of MCA’s Universal Amphitheatre. Backstreet’s roster included Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, J.J. Cale, Nils Lofgren, Men Without Hats, and Walter Egan, soundtrack albums to “Where the Buffalo Roam,” “Nighthawks,” “The Border,” “Cat People,” and “Doctor Detroit.” Backstreet was absorbed into MCA Records in 1983.

Among the films Bramson has also worked on are, “The Indian Runner” (1991), “The Getaway” (1994), “City of Angels” (1998), “Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), “Mission Impossible III” (2006), and “Jimi: All Is by My Side” (2013).)

When you are writing a script do you sometimes think, “I have a great piece of music for this moment.”

Yeah, always. Sometimes I will be stuck. So I will go to the grocery store, and whatever, and I have on my mix (of music) and something will pop up, and I will just realize that the key is to use this piece of music or something like it. It has always been my way out of a writing tunnel in script form. I play music on the set to kind of set the mood. We have often hired actors based on auditions that were done to music with no dialogue, and you are really able to see who soaks up music. Mostly, if you love music, it is your friend on camera. Some people are porous in that way. Some actors like Tom Cruise, they eat it up. And some of our best stuff happens with him acting to songs that we are playing on the set. Often, it doesn’t work in the finished movie, but it works to get you in the mood on the day (of filming).

I used to tell my mom, “I want to be either a writer or a DJ,” and on days like that I feel that I am a DJ. That I found different ways to DJ. I wanted to write something that could be a movie where we make it, and play music on the set. It’s reverse DJing or something, but it’s a real joy. And when you are in the editing room, as you well know, it’s a beautiful little cave to be in. You are just throwing some of your favorite records onto some cinema, and sometimes there’s a beautiful marriage that happens.

The scenes that still get me are the Harvey Keitel and Robert DeNiro characters walking through the club in Martin Scorsese’s 1973 film “Mean Streets” with the Rolling Stones “Tell Me,” and “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” You can’t imagine any other music in those scenes.

That’s when you know you are in the hands of someone who knows music. A music supervisor didn’t come in and tell Martin Scorsese to do that. He did it himself. Of the current directors, I’d have to say that Quentin Tarantino continues to be great. I don’t think I ever got over my broken heart that he used “Didn’t I Blow Your Mind This Time” by the Delfonics before I could get to it. Edgar Wright is also an assassin with the music cues in his movies.

Your use of Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” in “Almost Famous” is an iconic cinematic happening. It wasn’t then an established hit, At the time, it was a minor album track, the opening song on his 1971 album, “Madman Across the Water.”

(Due to its length of 6:12 minutes, “Tiny Dancer” was initially dismissed as a single in America, and with various station edits, it only reached #41 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. It wasn’t released as a single in the UK. It fared better in Canada, peaking at #19 on the RPM Weekly chart.)

Elton gives you credit for rejuvenating “Tiny Dancer,” and it really captured the time so well.

I know. Elton John is one of the only guys who names his sources, and it is really generous of him. He started doing that almost immediately after the movie came out. He helped us get the movie seen. He went on “The Larry King Show” and talked about “Almost Famous.” He said, “I always loved that song, but it never had a boost, and now it has, and it was always my dream for the song.”

How did you come to pick “Tiny Dancer” for the film?

For me, that song was a part of a concert, one of the first concerts I’d ever been to, and, like in “Almost Famous,” my mom was very strict, and she didn’t like the idea of her kids going to concerts where pot was smoked. Basically. “You get addicted to drugs as soon as you buy the ticket,” was kind of her thing. But Elton John was playing down the street, and I got permission to see that show with my sister. He played “Tiny Dancer,” and it was a galvanizing moment for me because I loved the song. It reminded me of the freedom of just turning your heart over to music. So when I was writing the script, I put “Tiny Dancer” in there. Not really knowing if “Tiny Dancer” would ultimately be the song that would work in the movie. I just loved it myself.

We had done “Say Anything…” before, and nothing fit the boom box scene in “Say Anything” (1989), except this one Peter Gabriel song (“In Your Eyes”) and we just got incredibly lucky there. But I didn’t know if we were going to get that lucky again. The “Tiny Dancer” sequence was actually four sentences in the script. When we started filming it, and the scene really started to take off, John Toll, our great cinematographer said, “Well, to cover this scene properly, to really do what you are trying to do, you have to spend two days getting it right, and it’s just a few lines in your script. So something else is going to suffer. So we decided whatever else was going to suffer that the penalty of going over on this one little scene in a few days. And, we did go over and the studio costs did show up, and they did basically throw ups against the wall and say, “You are over budget. What are you doing? You spent two days on people seeing a song. You are in trouble if you don’t pick up the pace.” We really got leveled.

But those things turn into the best moments of many films.

I know. When we put the movie together, they were like, “Can you make it (the scene) longer?” The other thing that is the soul of the movie was another situation where they were like, “You don’t have time to film this. What are you doing? That was Kate Hudson dancing on the empty floor of the Agora Ballroom (in Cleveland), as it is in the movie. Just dancing on the floor with the trash under her feet. But feeling the vibe, and spirit of what had happened in that room, where 2,000 people were screaming an hour earlier. And so we filmed her dancing, and it’s my favorite thing in the movie. Once again, you never know if the tiny little nugget that you almost cut but that you filmed ends up being the perfect of the entire thing. So I am always out there trying to throw a net for the quiet musical moments because sometimes that is everything.

As we talk about that scene, I think of “The Load-Out” by Jackson Browne from his 1977 album “Running on Empty.” It’s a tribute to his roadies and fans at the end of the night.

Exactly. Nobody writes about that moment.

(“The Load-Out” was recorded live at Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Maryland on August 27, 1977, as part of the tour in support of the album “The Pretender.”)

Across his career, Elton John has had 57 Top 40 hits in the United States, with 27 titles hitting the Top 10 and 9 reaching #1. His ‘70s period was extraordinary: “Your Song,” “Levon,” “Rocket Man,” “Honky Cat,” “Crocodile Rock,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “The Bitch Is Back,” “Philadelphia Freedom,” and “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting.”

An amazing chart run.

He was a machine in that era. Well, he still is a machine.

You had four Led Zeppelin songs in “Almost Famous.” You came to the band hat in hand for a meeting in London. You timed it to the one day of the year Jimmy Page and Robert Plant got together and went over tapes and talked about Led Zeppelin business. At the end of that day, they came to watch your movie in the basement of a hotel.

So it was just Joe Hutshing the editor, Danny Bramson, and you in the back row, and Jimmy and Robert three rows from the front, sitting together. Watching behind, you saw their heads framed by the film. They would lean in, and say things to each other.

Nervous?

In a big way. In a very, very big way. It is like the artist reading your story in front of you which is always frightening. You never know how it is going to go. You generally don’t want to be there.

Or screening a finished film for the studios guys.

Oh, it’s brutal. We showed Billy Wilder “Almost Famous,” and that was a nerve-wracking experience until Kate Hudson says, “What kind of beer?” And then he laughed. And that guy was a tough laugh. You have to be really funny to make Billy Wilder laugh. I don’t think I’d ever heard him laugh before then, but it was a real slow sound that builds into kind of an a-ha sound. Fantastic. That was incredible.

But we were showing “Almost Famous” to Jimmy Page and Robert Plant on the one day that they got together every year to go over things, a very infrequent business meeting day. They had compiled everything into one day when they’d go over everything.

Probably hating doing that kind of business day too.

I’m sure they did. They were probably very slow going with a lot of , “That person is saying that?” So at the end of the day, they are going to watch this movie. So it was with this small screen room, and we showed them “Almost Famous.” What was great was they were down three rows in so we could see the silhouette of their two shaggy heads coming together when they wanted to whisper about something. So they had been doing some whispering, and Joe, Danny, and I would look at each other and go, “Oh, we are sunk.”

Then came the infamous “I am a Golden God” scene.

Then came the scene when Billy Crudup and Jason Leigh say, “Well he has you on the top of a fan’s roof yelling “I’m a golden God.” And Billy Crudup is like, “I didn’t say that.” And we hear Robert Plant calling from out from his seat, “I said it.”

Quiet high-fives among you, Joe, and Danny?

Oh yes.

(Following the screening, Cameron Crowe was granted the right to use one Led Zeppelin song–“That’s the Way” from their 3rd album, “Led Zeppelin III,” released in 1970–on the “Almost Famous” soundtrack—the first time they had ever consented to do this since allowing “Kashmir” in “Fast Times at Ridgemont High”—and he was also given rights to four of other Led Zeppelin songs. “The Rain Song,” “Bron-Yr-Aur,” “Tangerine” and “Misty Mountain Hop,” in the film itself, although they did not grant him the rights to “Stairway to Heaven” for an intended scene.)

You were born in Palm Springs, California, the youngest of three children. Your father, originally from Kentucky, was a real estate agent, and your mother worked as a psychology professor, and in family therapy. Your family moved often, but at age 10, you lived in the desert town of Indio before finally settling in San Diego. Where is Indio?

Indio is outside of Palm Springs (23 miles east) in the Coachella Valley (of Southern California’s Colorado Desert region). Here’s the thing about Indio, Indio was so hot because of the desert that it was too hot for dogs, and people would have tortoises as pets. So that was a big thing. The other thing was that it was the date capitol of the world. Everybody had these date trees in their yard. And once a year there was the Date Festival on the fairgrounds just outside of town.

The thing was that this dust swept fairground play areas in Indio people would say, “Nothing is going to happen here.”

Well, of course a few years later. They decide to do the famous Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival (starting in 1999) just outside Indio (and the Stagecoach Country Music Festival starting in 2007). If a person from the future had come to me when I was a little guy in Indio, and said, “Yeah that place just across town where they are talking about tearing it all down, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and Neil Young are going to be there in a couple of decades.”

Surely, a “Back To The Future” moment.

That would be the “Back To The Future” moment where you’d get the greatest seat ever at the Coachella Festival because you were told by Future Man. So living in the desert was a big deal.

(Desert Trip–the three-day extravaganza from Oct. 7-9, 2016 at the Empire Polo Grounds in Indio, California brought together the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Roger Waters, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and The Who.]

(Today, Indio has over 93,000 residents. It began as a railroad town in 1876 as the Southern Pacific Railroad built lines between Yuma, Arizona, and Los Angeles, California. The engines needed a place to refill their water.

California grows 90% percent of all dates in the U.S. and most of them come from the Coachella Valley. At the end of the 19th century, the Department of Agriculture started a program staffed with men who traveled the world to look for new crops to bring back to America. Botanists traveled to the Middle East, and North Africa to study date growing, and concluded the dry, arid lands of the Coachella Valley would be the perfect place to foster commercial date groves which have flourished ever since)

One overriding thought about living in a small town when you are young is, “Get me out of here.”

True. Very true. Let me be cool somehow.

You were never going to be cool. Like me, you were the class clown. You were “Get Down Clown,” as Glenn Frey nicked-named you years later.

Exactly. I miss Glenn Frey a lot. He was one of those guys who, if he liked you, he gave you a nickname. And if he didn’t like you, he still gave you a nickname, it would just be a little more weaponized. He was the one who nicknamed Irving Azoff, his manager, “His Shortness.”

You also skipped kindergarten and two grades in elementary school, and by the time you attended high school, you were quite a bit younger than the other students. Also, you were often ill because you suffered from nephritis—what used to be known as Bright’s disease—and you were off school a lot due to glomerulonephritis inflammation which adversely affects kidney function.

Nephritis would take any color out of your face and would make you kind of yellow.

Maybe this is why I came to love Seattle so much later because I could be as pale as I was, and nobody would look at me and say, “Oh you are not a surfer. What’s your problem?” I was just another pale guy up in the North West.

What was the impact of the death of your sister in your family? You are the youngest member with two older sisters. A family never quite gets over the death or even a severe illness of a child.

Well, this is something that Joni talks about, frankly.

At age 9, Joni contracted polio, and I recall her mother Myrtle telling me about the difficulties of her long recovery.

Where, if you have come face to face with a life and death situation early in your life, it has an effect on you. You definitely look at things from a different perspective because you glimpsed the darkness. What is behind the natural frivolity of being young, Joni says, that is the difference between somebody like Billie Holiday and Edith Piaf and a random pop singer is that they have experienced this. It’s true my family had some stuff to deal with early on, and I think it gave us all a sense of empathy.

It also contributed to the character of the “Almost Famous” mother Elaine Miller (portrayed by Frances McDormand). There’s love very much evident, but also considerable anger underneath the performance.

If anything “Almost Famous” has that feeling flowing through it because the empty chair in the story which is the father in the film is omnipresent. That table is not the same with the person no longer there. It affects everything. And it affects the music that you need to uplift you and all of that stuff.

After filmmaker Steven Spielberg’s cameo in “Vanilla Sky,” he asked you for a favor. To do a cameo in his 2002 science fiction action film “Minority Report,” starring Tom Cruise and Cameron Diaz. While on a subway, you recognize Tom’s character from a moving image in USA Today while Cruise is giving you this look that is so viciously hateful.

You look a bit dazed.

I am. I am. He was getting ready to work with Tom after we were doing “Vanilla Sky.” So we drew him into a scene so he said, “Now you have to do one for me.” Sure enough, I get this call a year later, and I was told, “Come in for a fitting because Steven wants to put you in ‘Minority Report.’” I went in nervous for a fitting. It was a pretty cool Spielberg set. He knows exactly what he wants. He filmed pieces of scenes because he already has the cut in his head, and it’s amazing. Then I had to act. I am a terrible actor.

You are a fairly shy guy and acting is so demanding, even for the small bit parts you played in “American Hot Wax” (1978) as the delivery boy or in “Singles” (1992) as an interviewer or playing yourself in “Welcome to Hollywood (1998) or “The Other Side of the Wind” (2018) as a party guest.

We did one rehearsal on this tram where I see Tom Cruise has got a USA Today that has him on the front page, and they are looking for him. Anyway, I was so nervous. Spielberg said, “Let’s rehearse one.” So I did it, and I’m supposed to look up and see Tom Cruise, and I am supposed to be shocked because he’s on the front page of this virtual USA Today in front of me. So I did a rehearsal, and there was this kind of silence. I was like, “Oh shit. I knew that I should never do this.” Spielberg talks to Cruise for a minute, and he goes, “Hey, you are doing great.” I knew that I wasn’t doing great. Spielberg then says, “Let’s do another one.” He goes behind the camera and says, “Okay, let’s just rehearse another one (take). This is not for real but let’s just do it.” So he calls “action,” and I look up and Cruise is looking at me like Charles Manson times one million. I was really shocked to see the look on his face because I had worked with him, and I had never seen this expression on his face and it rattled me. All I remember is Spielberg saying, “Cut. Got it. We’re moving on.” But in the moments before he got that take, everybody was looking at me like a car wreck on the side of the road.

Was Tom in or out of character?

It was deeply in character. Obviously, Spielberg had whispered, “Okay, let’s just trick him. Give him your most Mansonesque stare. I will shoot the rehearsal, and we will get this.” And that’s what they did.

One of your most overlooked films is the romantic tragicomedy “Elizabethtown” (2005) starring Orlando Bloom and Kirsten Dunst that gave you the chance to explore Kentucky, and your father’s roots. I love your ex-wife Nancy Wilson’s score for that movie.

She did a beautiful score. She’s a wonderful scoring artist. I would ask her to work with us again for sure. I love her playing. I always have.

Nancy had also contributed “Beautiful Girl in Car” to “Fast Times at Ridgemont High,” and then had a small speaking part in “The Wild Life.” She contributed some music to “Say Anything…,” and wrote the musical score, theme, and incidental music for “Jerry Maguire,” “Almost Famous” and “Vanilla Sky.” Along with Peter Frampton, Nancy also coached Stillwater for “Almost Famous.”

To me, Nancy, Paul Simon, and Lindsay Buckingham are about the best you can find in acoustic guitar playing. And Joni.

Her guitar work has caught the ear of so many other musicians.

I have seen so many commercials that basically have done a “Nancy.” My message to those people is, “Hire Nancy herself.”

How did you and Nancy meet in 1980? Through interviewing Heart?

Neal Preston was photographing Heart and I asked him about Nancy. “I asked what was she like. He said, “She’s so shy. And I think that she’s breaking up with her boyfriend.” I was like, “Get me in there.” Ann, Nancy, and (Nancy’s friend) Kelly Curtis, and Neal Preston and I, we all went to that show “Fridays” together, and we had kind of a triple date. It wasn’t really even a date. But we went to the TV show where Heart had played as special guests a couple of weeks earlier. I realized that all of the guys on the show “Fridays” had a crush on Nancy. So I was sure I had no chance whatsoever to go out with her, especially because I was a rock writer and nobody (being a musician) would ever cross those boundaries.

As a rock writer, you were lucky to date any musician. You and Nancy married in 1986, and there was the birth of twin sons in 2000. The marriage ended in 2010.

I’m lucky I ever got my name mentioned to her as a rock writer. So basically, it was a miracle that turned into a wonderful time together.

Are you doing any more music documentaries? You did “Pearl Jam Twenty” (2011), “The Union,” about the making of Elton John and Leon Russell’s collaborative album (2011), and you co-produced “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” directed by A.J. Eaton (2019).

Why would you tackle these? Between projects, perhaps.

For various reasons. It was something that felt like it would be good in-between stuff, but now because there’s a boon for rock documentaries, we get asked a lot to do documentaries because everybody wants them. Larry, you got in there and did documentary work before this kind of avalanche. Now, it’s like every band, every artist wants a documentary or to do a series. I feel there has never been a better time to make a movie which is what we are going to do this year.

“Pearl Jam Twenty” was a natural for you given “Singles” where there was an alienation with Seattle Gen X’ers and talk about the death of rock. Pearl Jam members both appeared in the film and performed two previously unreleased songs on the soundtrack: “Breath,” and “State of Love and Trust.” So, a celebratory Pearl Jam doc is a natural for you.

Yeah, Pearl Jam is great. They were big friends of ours up in Seattle before there was any inkling of the success that would happen. So that felt like family.

Elton and Leon?

Elton John basically said, “Get a camera, and come over here, and start filming. I’m going to make a record with Leon Russell. I love Leon Russell. Here is something that Elton John also said, “Nobody has ever filmed me writing. They have filmed me doing everything else, but nobody has ever filmed me writing. So you get a camera and come over here, and I will let you film me writing. And Bernie (Taupin) will be around, and you will see the thing that we always talk about, and we’ve never let be filmed. So I was in for that.

Crosby I have written about a lot because of CSN&Y. I have not had any bad experiences with Crosby. I had always known him as the guy who if you interviewed him, was going to be a lively conservationist.

A long line of Crosby acquaintances, including Graham Nash, Neil Young, Roger McGuinn, and Joni Mitchell, won’t have anything to do with him.

As he tells you in the documentary, there are a lot of people that have issues with him, but that stuff just makes it sparkle and light up as he tries to tell you what his opinions are on it (the feuds) are. Say what you will about David Crosby, he is on fire creatively now.

In the first interview, you did with Crosby for the documentary, he told you, “Time is the final currency. What do you do with the time you have left?” Okay, that’s a theme to follow, because he’s looking forward while looking back, and that was obviously the key to the film. Then there’s the ending when he has that look on his face as if he considering his entire life in a blink of an eye.

The camera loves him, Larry. The camera loves this guy and A.J. Eaton was the director even before I was involved. I just told A.J., “Don’t do a million talking heads. Just put the camera on Crosby and let him go. He’s like the Lamborghini of quotable quotes. Let him talk really close to the lens, and make it sound as if he is telling one person these stories, and it could be a film.” That was the beginning of the Crosby doc.

We each have had tough interview encounters. Lou Reed was challenging as was Frank Zappa to me. Once he was great with me as we talked about R&B music in L.A. in the ’50s. The next time, he was a jerk. I had John Mayall for a radio interview, and he was so abusive to the label rep that I threatened to throw him off the air.

I interviewed Buddy Miles (drummer in Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys and co-founder of Electric Flag)—once, and he had a knife, and he started sharpening it while bitterly answering questions. I think when I asked him if he felt a kinship with the way Chicago Transit Authority used their horns compared to the pioneering use of horns he’d brought to the Electric Flag, he considered using it on my neck. This is the same guy who came to Rolling Stone’s offices looking for Ben Fong-Torres, and not in a good way.

What are your favorite vintage films?

Probably “City Lights” by Chaplin. “8½” by Fellini, and Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment.” For any aspiring writer or director, almost any Billy Wilder script will be your holy grail. Story, story, story… nothing beats a good story filmed well, with great music to help out.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record.

He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is a co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide,” and a Lifetime Member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

He is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.