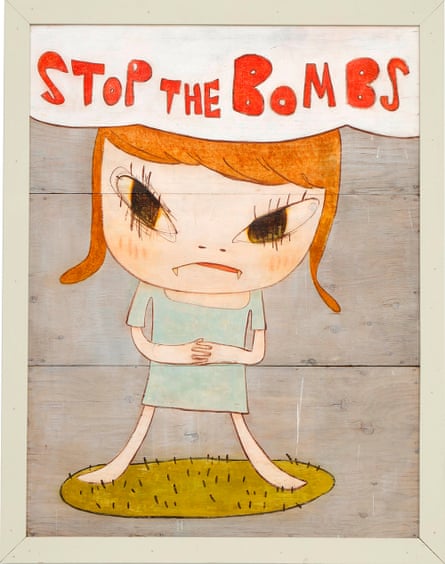

“Stop the bombs” reads the angry red writing in the storm cloud thought bubble above the little girl in a pale blue dress. Like all the children in the Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara’s paintings, she has puppydog eyes and a toddler’s outsized head, yet her posture is pure bruiser. There are tiny animal fangs at the corners of her mouth. Of the paintings, drawings and sculptures in Nara’s latest exhibition, she is the closest to the pint-sized characters with big dark feelings that he began making in the 1990s, some of contemporary art’s most recognisable creations.

Those early works, where tots sweetly clutched knives or took fag breaks, blended Japanese kawaii – cuteness – with mischief and menace. Partly thanks to Nara’s alignment with the pop art titan Takashi Murakami’s Superflat movement, he reached a global art audience and a wider public. Both artists mined the Japanese weakness for baby-faced adorableness, an infantilising that Murakami linked to the trauma of Hiroshima. Yet where Murakami’s trademark smiley acid-faced flowers and phallic mushrooms channel the surface sheen of a depthless mass-produced world of cartoons and commerce, Nara’s appeal has always been universal human emotion. “My works’ roots are my childhood, not pop culture,” he explains. “Around me there were orchards, sheep and horses; I read fairytales rather than comics.”

Once described by the artist as self-portraits, his paintings communicate as powerfully as the folk tunes that first inspired him as an isolated child listening to the radio from the US air base in Misawa, or the punk rock he later turned to, creating artwork for cult bands such as Shonen Knife. While Nara’s figures recall saccharine anime, his paintings are expressively hand-wrought, with cardboard or wood planks often used in place of canvas.

In recent years, his blackly comic tykes have given way to a more introspective tribe. The latest works include girls with huge eyes flecked in many colours, who stare into the middle distance as if lost in life’s great imponderables, or close their eyes in meditation. Even his guitar- or drumstick-wielding mini rock chicks seem spaced out, depleted of punk’s riotous energy. Nara has created an installation from abandoned building materials in which to show many of his works, like a cross between a clubhouse and a protective retreat.

There are a few protesters among the new girls. One wears a “no war” slogan T-shirt, another flips a peace sign, stirring thoughts of Hiroshima and the anti-nuke movements, as well as today’s demonstrations. The turning point for his work’s tonal change, Nara says, was the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that led to the Fukushima nuclear accident of 2011. “Fifteen thousand people within the 650km from where I live now, north of Tokyo, to my home town, were killed,” he says. “I felt an enormous sense of loss.”

The gap between his figures’ pluck and physical powerlessness is striking: little people up against insurmountable forces. They speak to adult angst and the vulnerable child inside us all.

Pinacoteca, 2021 (main picture)

Taking its title from the classical term for a public art salon, Nara has created an installation from wood and building cast-offs in which his latest works are displayed. “I’ve always felt quite uncomfortable with architecturally solid spaces such as museums,” he says. “To me, places that have a temporary feel such as huts feel more familiar.”

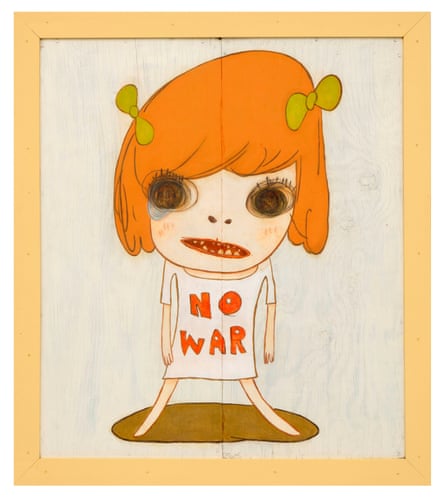

No War, 2019

Nara’s paintings typically draw on his childhood experiences. “I was nurtured by the civil rights movement’s protest songs and the anti-war movement’s rock songs,” he says. “Also, the Vietnam war didn’t feel like something that happened in a faraway land, as American troops were dispatched from the military bases in Japan.”

Stop the Bombs, 2019

A number of Nara’s recent paintings reference the 1960s, its protest symbols and hippy culture. Here he was thinking of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1968 “living sculpture” in which two acorns were planted in the east and west gardens of Coventry Cathedral. It was the same year as the adoption of the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

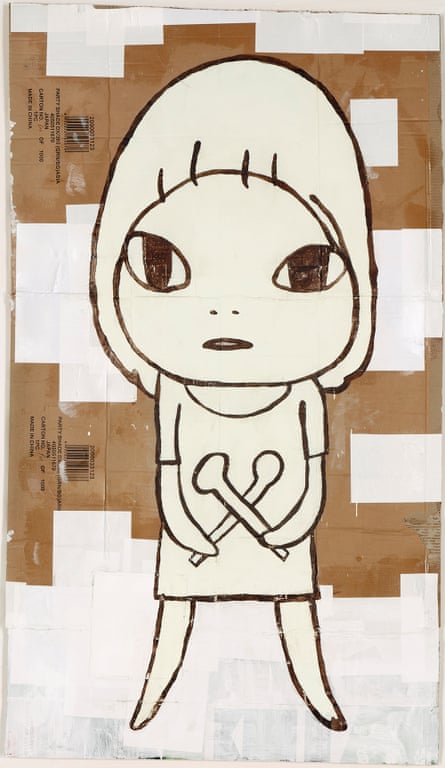

Girl With Drum Sticks, 2019

Music is key to Nara’s process and, while punk has been a touchstone, in recent years he has turned to the folk songs he heard on US military radio as a child. He explains: “I was influenced a lot by hippy culture with its emphasis on community and nature as in: ‘Back to nature’, and, ‘Living is not breathing but doing’, in the words of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.”

Yoshitomo Nara: Pinacoteca, Pace gallery, London, to 15 Jan.