Was This Alex Honnold’s Closest Call?

"In our analysis afterward, we agreed that we were extremely lucky."

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

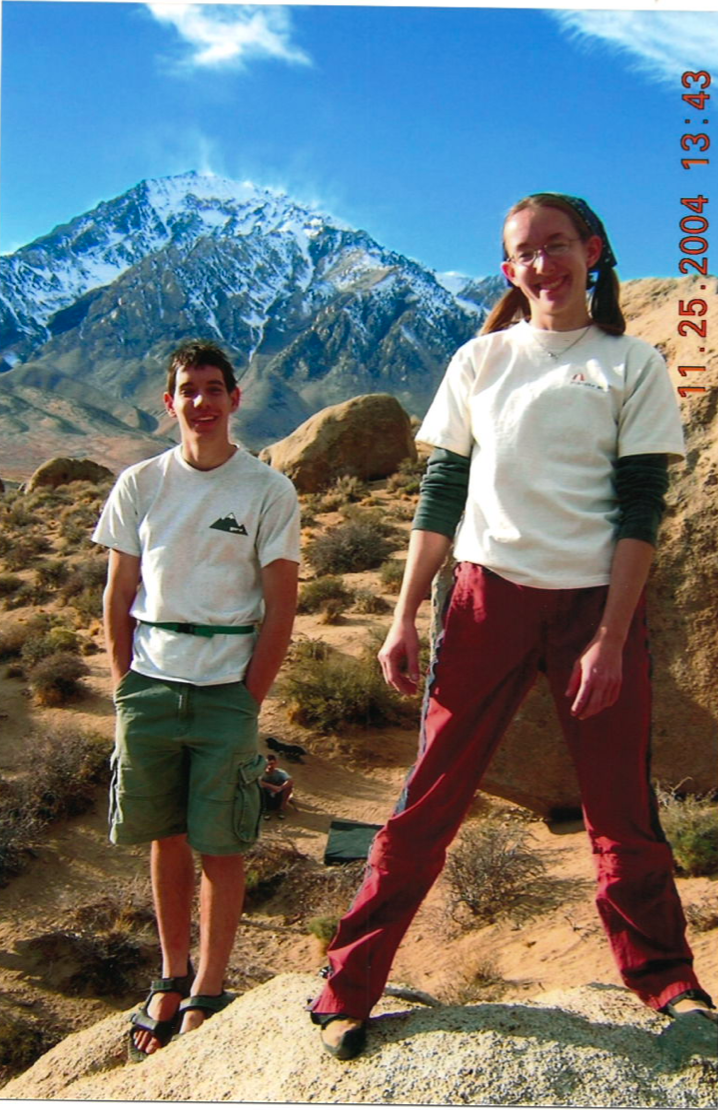

I know that Alex Honnold thinks about the risks of rockfall. I know this because I was with him the first time he—and I—experienced it.

We were climbing at Mayhem Cove in Tahoe, a crag of zebra-striped granite, back in the summer of 2005. It was the first clear day after several rainy ones, and we were eager to get out on the rock. At the time, I had just turned 25, and Alex was about to be 20.

To be fair, Alex was always the most eager to climb of anyone in our circle. I had started climbing in college in Bloomington, Indiana. After graduation, when I moved across the country to Sacramento to take a job at Intel as an SAP systems analyst, it took me a few years to find a crew of climbers as psyched as I was.

I practically lived at the climbing gym in those days. Coming straight from my job, I’d drive there and meet my friends to climb until close. I spent so much time at the gym, climbing, setting, and socializing, that the manager once called me during the day to ask if I could work a shift that Thursday. I paused and replied, “Uh, I don’t actually work there.” I hung up and turned back to the computer in my cubicle, where I did work.

At the gym, Coach Charlie had been training a lot of the younger kids (including Alex and his friends Claire and Doug). Charlie also offered a three-month class that took me and my older friends from 5.9 toproping to 5.11c leading, and he introduced me to bouldering outdoors. I was hooked.

A really shy kid named Alex was hanging around a lot at the gym. I heard he’d dropped out of college at Berkeley, only ate hardboiled eggs and Oreos, and that his dad had just died. He loved climbing, and he was clearly good at it, but most people couldn’t figure out how to get him to talk. I guess I liked the challenge, and for some reason Alex eventually decided to trust me.

An Insatiable Hunger for Climbing

Even more than the rest of us, Alex could not get enough climbing. Once he wasn’t at school and didn’t have to work, due to his dad’s life insurance paying out, all he wanted to do was climb. We became weekend climbing buddies, since my 8-to-5 kept me tied up on weekdays.

It was never enough. During the week, Alex would beg the rest of us to take a day off and come up to Lover’s Leap with him. We wanted to, but we all shrugged and said that we had to work. So he started going by himself.

Alex would return and admit that he’d started free soloing. We were stunned. Normal people don’t solo! Eventually, Alex started soloing at the gym after hours. The unspoken idea was that if we—his climbing pals and peers at the gym—let it slide indoors, with its shorter walls and padded floors, and where we could call 911 if Alex did fall, he might get it out of his system and stop soloing on rock, where the stakes were much higher.

We were wrong.

The challenge of finding a challenge for Alex continued to grow. He was always so restless. One night, he talked me into taking a rope swing in the gym. In retrospect, I never should have agreed to this, but his confidence changed my mind. It was one of the top-five most terrifying experiences of my life. I like to measure things and take calculated risks, but for some reason we didn’t measure how much rope to use. Alex just eyeballed the swing and told me to jump from the rafters and hold on. The pendulum was supposed to be massive, but I thought I was headed straight into the ground first. When I bring up this story, Alex has no memory of it. Didn’t even chart for him. He just grinned his huge, goofy grin and was on to the next thing.

The hardest climb in the gym was built into the natural features, rated 5.13a perhaps. Alex had it so dialed that he started climbing it blindfolded. There was a long traverse problem in the bouldering room. When a new woody was put up across the room from the traverse wall, Alex extended the traverse by launching himself like an ape from the top of the old wall onto the woody, where he continued climbing. No one else would think of that.

Despite all the fun and adventures, I knew our friendship was based on our conversations and observations of the world. We rarely talked about climbing. After the gym employees would kick us out, we’d often sit in my car and talk for another hour or two before heading home. I regularly ate dinner at midnight.

We swapped books—1,000-plus-page tomes like Mark Helprin’s A Soldier of the Great War— both of us constantly seeking challenges. We talked about family, his parents splitting up, his secret girlfriend, my boy-crazy crushes, my job, my religion and his atheism, music, courage, the purpose of life, everything.

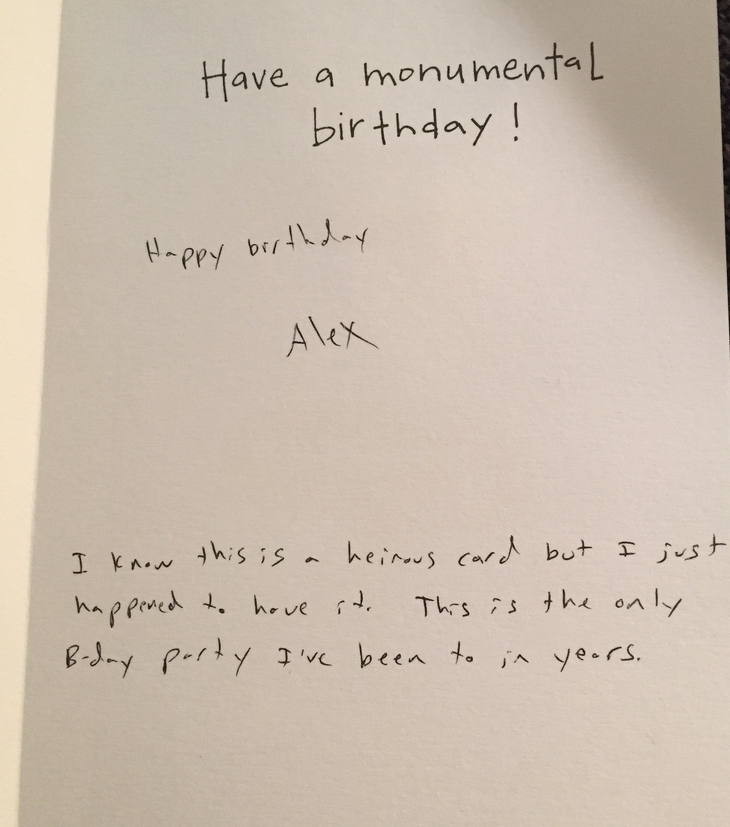

I still have the birthday card he gave me one year when I invited him to a cookout at my house. He scribbled something about having not been invited to many parties recently, so his card was “heinous” but it was what he had. Pure Alex.

Along with forcing him to come to social events, I was a hugger. For a while, hugging Alex was like hugging a fence post. Finally he warmed up and learned how. It just hadn’t been part of his life before, and I think he appreciated the normalcy of it.

We soon became weekend-warrior climbing buddies. If Alex drove, we listened to his horrendous heavy metal, bands like System of a Down. If I drove, it was lyric-twisting hip-hop or catchy dance music, which he tolerated with eye rolls. We spent so much time in the car together that I was there when he was pulled over for speeding, and he was there when I got pulled over another time for the same thing. Whoops!

Mayhem Cove

The weekend of “the incident,” Alex was staying at the family cabin in Tahoe, and I drove up to meet him that Saturday. Before heading out to climb, I took a walk with his grandmother, whom he adored, and his sister, also someone he talked of with utmost respect. The weather was perfect.

It was our first time at Mayhem Cove, which Alex had picked because it had a quick approach to harder and more overhanging climbs than we normally found at the classic walls in the area—like 90-Foot Wall, Pinnacles, or Sugarloaf. Mayhem Cove was full of 5.12s and 5.13s; I was eager to follow him up a 5.13, a grade I’d never tried outside before.

The ground was severely sloping under the climbs, but we figured out a way to tether me in while I belayed. Alex hopped around the sloped staging area like a grasshopper on a log, while I felt like that log was liable to roll hundreds of feet down onto the forest floor or into Lake Tahoe. I remember attempting a 5.13a that day, and it might have been Alex’s first solid go at one outdoors as well. I followed him on toprope, hanging at each draw but exhilarated by the dramatic roof moves.

After that, we moved to a more vertical wall around the corner. Alex picked a 5.12b called India Ink, onsighting it easily while hanging the draws and setting up a slingshot toprope for me. The route was only 50 feet tall, with the crux close to the top. The lower part of the route was more straightforward, though a bit runout since it was easier climbing.

I took off my light-gray approach shoes, setting them beside our gear directly below the climb. We checked each other’s setups, and I headed up to try the route.

Just before the crux, there was a gap: a foot-high horizontal crack that shot about two arm-length’s deep into the rock. I was unclipping the quickdraws from the rope but leaving them on the hangers to grab on the way down, since India Ink was only just past vertical. There, just below that second quickdraw, I was maybe 25 feet off the ground, given the scramble at the bottom.

I stuck my arms in the horizontal crack, placed my feet, and shook out, catching my breath. Soon, I felt recovered and ready to climb. With my hands deep in the gap, I levered off my feet—then felt something shift. A chunk of rock about the size of a football came loose from under my hands and tumbled down toward Alex as fast as I could scream, “Rock!”

Alex jumped out of the way, and I sagged onto the rope. I’d swung out only a bit, but I was startled.

“I want to come down!” I yelled.

“No! Suck it up!” Alex said. This was typical from him, always telling me with a straight face to “try harder” when I asked for beta on a move I’d been trying over and over. It usually pissed me off enough to actually work. We argued briefly about whether I should go on or not, and finally he convinced me to try again. I’d never broken off such a big chunk of rock, and my main mantra when I got scared outside was something like “It’s rock. It won’t move.” However, I’d just proven this mantra false.

To avoid any further rockfall while belaying, Alex talus-hopped nimbly back and off to the side, leaving our gear where he’d been standing, directly below the climb.

I kicked and swung like a pendulum to get back on, and then took a minute to regain my composure. I remember staring hard at the moss that was snaking its way between the rock’s cracks, and then taking a deep breath. Gathering my courage and strength, I again levered off holds deep in the gap, as if pulling back the flap on a large box. Just then, everything underneath me melted away.

One moment I was attached to the rock, and the next, there was just nothing. Everything I was holding had evaporated. The noise was thunderous.

A refrigerator-sized rectangle of stone—the panel forming the bottom edge of the crack—shot down the wall, along with more football-sized chunks, which had seemed huge to me only a few moments earlier but now paled in size to the main event. Because the ground was angled, the rocks tumbled past the staging area after they impacted, roaring down the hill.

The noise was like standing right under a huge waterfall, nature showcasing its awesome power. Looking down, I frantically scanned the cliff base for Alex, hoping he was OK—and there he was, just off to the side of the rockfall, where he’d moved just one minute earlier. Alex’s jaw dropped as he watched the devastation, but being the solid belayer that he is, he held onto the rope. I dangled in wide-open space where there had previously been rock.

I shrieked and started sobbing, and this time Alex made zero protest when I asked to be lowered. As I landed back on terra firma, Alex ran over to check on me. I untied as fast as humanly possible and sprinted away from the untrustworthy wall. The kindness and empathy Alex showed me in that moment is why I imagine he will be a good dad. He recognized how scared and shocked I was, and he patiently waited beside me until I calmed down in my own time.

There were only two other people at the crag that day. Having heard the crashing rocks, and probably my shrieking, they yelled from around the corner to ask if we were OK. We confirmed that we were, as we carefully poked back around the debris to collect our gear. After a bit, Alex toproped the upper half of the route to clean the remaining draws—we were both poor enough at the time that it would have stung to leave them behind.

However, we never found the first quickdraw, which had been clipped to a bolt drilled into the refrigerator-sized block. Meanwhile, a large chunk was missing from my approach shoe, cut clean off by the falling stone. If Alex had not moved when the first smaller piece of rock fell, I have no doubt he would have been killed by the later, larger rockfall.

In our analysis afterward, we agreed that we were extremely lucky that the massive block hadn’t cut loose during Alex’s lead. He was twice my size, so it didn’t make sense that it was me who’d dislodged the rock, but sometimes that’s how it goes—rockfall can be random. Meanwhile, my new mantra became “Pull down, not out,” and I don’t get on any rock anymore after the rain. It’s not worth it.

When we talk about that day now, Alex always mentions how we went out for ice cream afterward. He said he thinks of this story every time he visits that ice-cream shop in Tahoe. While we climbed in Tahoe many more times after that, I only returned to the family cabin briefly years later to quickly clean up, when he asked me to be his guest at an event after a long day of climbing. He was between girlfriends and needed a plus-one to receive the Golden Piton in 2010.

I remember other well-known folks like Todd Offenbacher and Corey Rich politely asking who I was. I shrugged, smiled, and said, “Nobody, just a friend,” knowing they just wanted to know if I was also famous, or his girlfriend. I was comfortably neither, but felt pride in knowing Alex as well as family at the time, laughing as people bought him drinks all night, knowing his secret that he didn’t drink alcohol.

Alex and I don’t get to hang out regularly now, as life has taken us to different cities, but we pick up easily when we do. In 2015, we were both Brazil at the same time, him for “work” and me for vacation, and my boyfriend and I spent half a day walking the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema with Alex and catching up. He whined about having to take a rest day, but I think he still had a little fun, as I’m pretty sure that day also involved ice cream.

Of that fateful day in Tahoe, I have no memory of the Tahoe ice-cream shop nor of the drive home. I do, however, remember writing an email to Chris McNamara the following day to inform him of some changes to India Ink, since he maintained the online beta and did guidebook work for the area. In particular, I let Chris know that the new first bolt was now “very, very high.”

Renée E Ross currently lives in Salt Lake City and works remotely as a manager at Apple in the Developer Tools software engineering group. She still loves climbing, hip-hop, and long books. She wishes her old friend Alex only climbed on ropes, but she respects that he has made a good life doing what he loves.