We are not trying to make any politics. We are artists. But through our music we would like you to feel the agony … In Bangladesh.” Ravi Shankar speaking before he began to play at Madison Square Garden. The record of that concert will be released next Monday as a triple album (Apple STCX 3385), and all the proceeds will go to relief for Bangladesh (like the concert gate of $243,418.50).

Since he played in Monterey, Ravi Shankar became well known both to the rock music audience and also to rock musicians. George Harrison elected to be influenced by Indian music as soon as the Beatles played more than pop tunes: Revolver, released in 1966, shows the beginning of his self-teaching. (Brian Jones was influenced at the same time: Aftermath, also released in 1966, has him playing sitar). Harrison was always more concerned to deepen his ideas than to attempt the musically impossible; so, instead of emulating Ravi Shankar, both men have for years in effect been the others’ patron: George by placing his fame at Ravi’s service, Ravi by being, in the background, an altogether better Guru for Harrison than the Maharishi.

Ravi Shankar, a Bengali, asked Harrison for help to raise money for the victims of the war in East Pakistan last summer. The Madison Square Garden’s concert was the result, mounted in a month. The first side of the triple album has Ravi playing sitar to Ali Akbar Khan’s sarod.

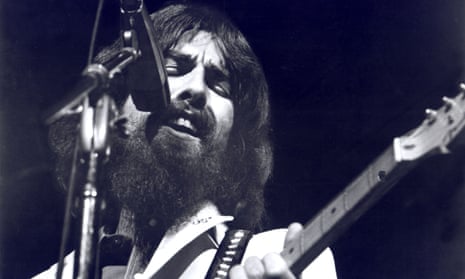

Side two is, in effect, a retake of the most memorable and characteristic of Harrison’s songs on All Things Must Pass (Apple STCII 639). Indeed, with some very notable exceptions to come, the lineup of musicians on The Concert for Bangladesh is similar to George’s earlier triple album. Eric Clapton joins him for Wah-Wah, My Sweet Lord and Awaiting On You All, with Leon Russell on piano. The photographs of Harrison at the concert show him with a long pointed beard, like a wizard, singing with eyes shut, almost wrenching the words from himself. The chorus behind, and the audience in front, rise to him, the girls in the band responding half Gospel-style, half as a mantra. The song remains rock; organ and piano punctuate the melody like pistons, guitars oil it, bending and shaping the beat.

My Sweet Lord was commonly recognised as the single of 1970. The song is an invocation, made not for protection, but in a state of bliss. Again, Harrison mixes East with West the chorus chant sometimes “hare krishna,” sometimes “alleluia.” The song is simple enough for it to be even better played here than on the previous studio track, Clapton’s guitar answering Harrison’s voice. The act of worship, amplified immensely by being made by star performers at the height of their fame and skill, almost becomes a beatitude. Each part of the song comes clear, Harrison infects a little cry not in the studio version. “Touch my cheek.” Listening, the effect is just that of the early Beatles’ hits: pleasurable shudders, and tingling at the finger-tips, almost evangelistic.

Two hymns end the second side, Awaiting On You All and That’s The Way God Planned It. Both songs are confident celebrations, ending abruptly in their own silence.

Just as the album has a picture of a starving child on its cover, so the audience at the concert must have heard words of the songs new. After Billy Preston sings “I hope you get this message,” Ringo Starr comes on to sing his It Don’t Come Easy. Horns and drums thrashing, the audience clapping and calling, he sings “open up your heart and come together.” Then Harrison again, reminiscent of Dylan in Beware of Darkness: “Watch out now take care, beware of greedy leaders.”

Leon Russell provides the secular feast of fun on side four, with a medley of Jumping Jack Flash, and the Coasters’ Young Blood, sneering and yip-yipping as good as Jagger, guitars weeviling down and through the sound, girl chorus squealing, Leon improvising the song’s links. The side ends with George singing his Here Comes The Sun from Abbey Road.

Side five: a roar of delight as Bob Dylan comes on to sing songs all of which he wrote six years ago or more, playing acoustic guitar and harmonica, singing as he used to. Clearly, he relates Bangladesh to his old songs’ concerns, giving them a new twist, another facet. Four years ago Dylan said of his early songs, which were taken as anthems by the kids, “I no longer have the capacity to feed this force which is needing all these songs. I know the force exists, but my insight has turned into something new.” And at other times he spoke of being made intolerably confused by the pressures put on him. Now, remaking these songs by singing them at the Bangladesh concert, Dylan brings them to the light again, reminding us of their value.

A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall – like most of Dylan’s songs elliptical and metaphorical – comes into its new focus. “Been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard”: and the audience see the newspaper pictures of the brown corpses. “I met a young woman/whose body was burning.” “The executioner’s face/is always well hidden/where hunger is ugly/where the souls are forgotten.” Here and now, the familiar words are hard to take: they are too apt, they point to sorrows too large to be grasped except by a poet. But here is the poet, in public. Dylan goes on to Blowin’ In The Wind, Mr Tambourine Man, to Just Like A Woman. He plays gently, within himself; perhaps to make plain that the show is Harrison’s.

The concert ends, relaxed, with George singing Something and Bangladesh. What Woodstock was said to be, the Madison Square Garden Bangladesh concert was. It’s on record. The concert will stand as the greatest act of magnanimity rock music has yet achieved.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion