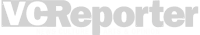

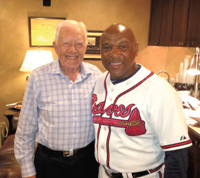

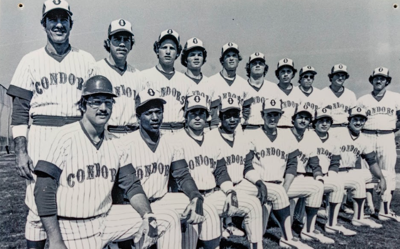

Pictured: The 1979 Oxnard College baseball team. Photo courtesy of Oxnard College.

by Kimberly Rivers

What does a close knit community look like? What stories get told about that neighborhood and what legacy does it have for the kids who grew up there? Sometimes that legacy is told by outsiders. But here is a story of a community, related by one of its cherished members. A person with a tremendous legacy, who grew up in the Colonia and Rose Park neighborhoods of Oxnard.

That person is Major League Baseball legend Terry Pendleton.

Terry Pendleton as a coach for the Atlanta Braves signing autographs for fans before a spring training game in March 2011. Photo credit details HERE.

Pendleton has gained considerable fame as a ball player for the St. Louis Cardinals and the Atlanta Braves, with a long list of achievements attached to his name – including Most Valuable Player in the National League for the 1991 season (beating out Barry Bonds). Today he is on the coaching staff of the Atlanta Braves, helping to bring them to their championship win in the 2021 World Series. But in talking about his life, career and baseball, he emphasized the valuable role played by the “village” of families who were a part of his community; people who raised him and helped prepare him for the ups and downs of a career in major league sports.

“It truly takes a village to raise a child. I want to list that village,” he said, adding that these were people who “shaped me . . . who gave a word of encouragement, showed me when I did wrong and helped me correct it.”

“I could walk into these families’ homes at any time and be as welcome as if I was their child,” he recalled.

“When you start something, you finish it”

Pendleton moved to Oxnard from South Central Los Angeles when he was 9 years old, and started playing organized baseball when he was 10. His godfather, Wallace Anger, was his first baseball coach; Pendleton played with Anger’s sons Victor and Manuel.

At the time, he had no idea of his level of skill, or what he would later achieve. He just kept at it.

“I remember being that kid in right field. I couldn’t hit a lick. In my mind I was the worst kid in the entire league. I was going home crying after every game because I was so bad at it.” But his parents were there to encourage him. He’d say, “I’m not going back out there, I’m embarrassing you . . . myself, I’m not going to keep doing that.”

Pendleton credits his father with keeping him in the game.

“My dad [made it clear] that when you start something, you finish it. There would be no quitting. So you decide how you would do it.” That approach to challenges played a key part in Pendleton’s development as a player and later as a coach.

When baseball season ended and winter came, Pendleton shifted away from football (the other sport he loved) to devote all his time to baseball.

“Victor Anger and I . . . would go to Rose Avenue Elementary every day after school, and during the Christmas holiday. We played a game called Strike Out.”

They would draw a box on the handball wall at the pitching strike zone. “We pitched to each other the entire winter.” He remembers using soda cans to mark the distances of their hits, either a single, double, triple or a home run. “So we’d know what kind of hit we got.”

The winter of Strike Out paid off. “Next year, I was the all-star shortstop. The Anger family pushed me big time, to be a better baseball player, a better person . . . along with the Colonia and Rose Avenue neighborhood.”

“FAMILIES IN MY VILLAGE” | Terry Pendleton provided a list of individuals and families from the Colonia-Rose Park neighborhoods in Oxnard whose homes he could “walk into at any time and be as welcome as if I was their child.” Some of those families have since passed away, “but their kids are alive. I want to make sure they get it, that I greatly appreciate them.” He calls many “big brothers” and added, “For any that I may have forgotten please, please forgive me.” GUIDING INFLUENCE | Bobby Fuller, Victor Anger, Manuel Anger, my big brother Ronnie Pendleton, Johnny Taylor, Ray Coleman, Greg Lee, Rodney McClain, Austin Diggs, Donnie Hairston, Ron and Don Thompson, Tom Doleman, Rod Patterson, Jeff Hershey, Frank Mosqueda, Gab Aguilar, Danny Inez, Danny Lemos, Dan Tullis Jr., Mark Hawkins, Larry Lee, Calvin Pleasant, Darryl Tullis, Craig Breland, teaching/coaching and staff at Channel Islands High School and Oxnard College, and the Oxnard Boys and Girls Club staff “for putting up with me.” THE VILLAGE FAMILIES | Anger, Decker, Lee, Pleasant, Hairston, Tullis, Thompson, Thomas, Diggs, Washington, Richardson, Saipole, Garcia, Valles, Vildasola, Baker, Arellano, Maulhardt, Lewis, Panapa, Brisslinger, Styles, Avila, Hernandez, Breland, Barnes, McIncas, Coughlin, Frash, Larsen, Longenecker, Rogers, Willard, Chambers, Ruffins, Marquez, Wallace.

He continued to play baseball through high school, but his focus had started to shift to basketball. Then, in his senior year at Channel Islands High School, he took home a slew of awards in baseball.

“I went to the Southern California Championships with [Channel Islands High School],” was named Most Valuable Player in the county league and made All State. “I was like, ‘What?’ Until I won all those accolades, I thought I was better at basketball. But still no colleges were after me to play anywhere. Not even small colleges. No scouts to sign me out of high school. I didn’t know how to measure myself and my ability.”

Flight of the Condors

Something special happened during Pendlton’s senior year. There were four or five players in Oxnard that didn’t get any college scholarship offers. Names like John Larson, Jerry Willard and others who played for Hueneme High. Jerry White, the baseball coach from Moorpark College, left to start a new team at Oxnard College.

“We all decided to play for him that summer and go in and play for Oxnard College,” Pendleton recalled. “The biggest piece of that was Coach White. And he picked up a few [players] from Camarillo, a couple at Ventura [College].” He also recruited a few Moorpark College players to the Oxnard team (called the Condors).

That was 1979 and for a first-year team, the Condors made an impact in the league.

“We won our division and won our league. We went to the Southern California Championships. We lost, but did very well; very, very well for a first-year team. They didn’t expect us to come out and do what we did in year number one.”

“I played on and off” that year, Pendleton noted. “I became a starter later when kids got hurt. I was a second year starter. Still, there were not a lot of scholarships.” After his sophomore year, the University of Arkansas and University of California, San Diego, showed some interest. “UCLA kinda promised me . . . But nothing ever came.”

“At the last minute,” an offer came from Fresno State University (FSU). Pendleton spent his junior year at Fresno State on a partial scholarship.

Riding out the ups and downs

“Division one was a learning experience,” he remembered. “I had temporary setbacks,” as he called them.

At FSU, Pendleton was benched or didn’t make the travel squad. “They left me back at school, I don’t know why. Those were temporary setbacks. I finally got the opportunity to play, then got benched [again].”

He had just 40 at bats that entire year. His partial scholarship was “taken away,” and to this day he doesn’t know why he didn’t play more that year. But looking back, he acknowledged that “it made me a better young man,” paying his “own way” by working at the unemployment office.

Pendleton continued to play, however. While he’d been an infielder, he ended up playing right field during his senior year. And that’s when his fortunes changed. Pendelton set a school record of 98 hits and was recognized as an All-American player that year.

Success in Fresno led to opportunities in the Big Leagues: Pendleton was drafted in 1982 by the St. Louis Cardinals in the seventh round.

“They didn’t care if you’re No. 1 or No. 53. We were all treated the same. You worked your rear end off to achieve . . . and get to the next level.”

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. In 1983 he fractured his right wrist – twice. The first happened when he was hit with a fast ball while at bat. The second time was on his 23rd birthday. “I only played six weeks, sat out the remainder [of the year].”

But Pendleton didn’t give up. He showed up for spring training in the minor leagues the following year, where he “worked my rear end off,” and made it to the AAA baseball club level with St. Louis. “I played well . . . batted 300 in AAA.”

A couple of days after his 24th birthday, “I got a call . . . ‘You’re going to the show.’” That’s what players were told when they were being bumped up to the major leagues. He’d be playing third baseman with the Cardinals.

“I remember calling home, telling my mom I’m going to the big league.” Then he called his fiance, “my wife to this day, Cathy Marquez.” They all said “yah right.” They thought he was playing a joke on them; he told them to pick up the paper the next day and look for his name.

Whitey Herzog (left), manager with the St. Louis Cardinals, with Terry Pendleton in 2017. Photo submitted

“Whitey Herzog played me the next day.” Pendleton got a hit his first time at bat, and hit three for five that night. “It was a pretty good first night.”

Star of the show

That was the beginning of a 15-year career in the MLB as a player, which included six appearances at the World Series. After the Cardinals, he moved to the Atlanta Braves . . . where he once again rode out a series of ups and downs that come with the sport. His persistence paid off: In 1991 he was named MVP in the National League.

Even then, as a now-famous ball player, Pendleton never forgot his roots. Throughout his MVP season, he often wore an Oxnard College Condors shirt under his Braves jersey to serve as a reminder of where he came from.

MVP is just one of Pendleton’s many career highlights, which include three Gold Gloves (’87, ’89, ’92), MLB Comeback Player of the Year Award (’91), Silver Bat Award (’91), 140 career home runs and an appearance in MLB’s All-Star game (’92). His World Series appearances span from the 1980s to 2021.

Over the years, Pendleton has supported Oxnard College’s baseball program by donating time, money, equipment and even memorabilia. He was inducted into the California Community College Athletic AssociationHall of Fame in 2016; the award is permanently displayed on the Condors’ outfield wall. This year Pendleton has been recognized as a California Community College Distinguished Alumni by the Community College League of California (CCLC), a statewide organization that advocates for California community colleges at the state and federal levels.

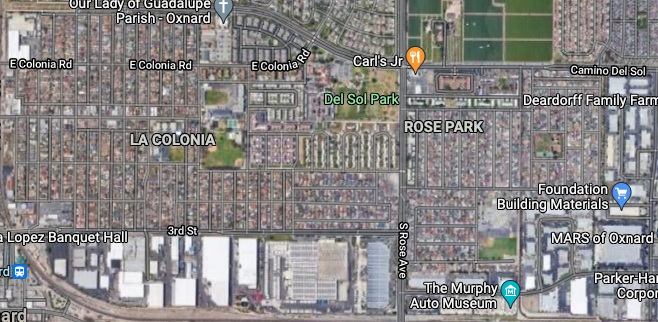

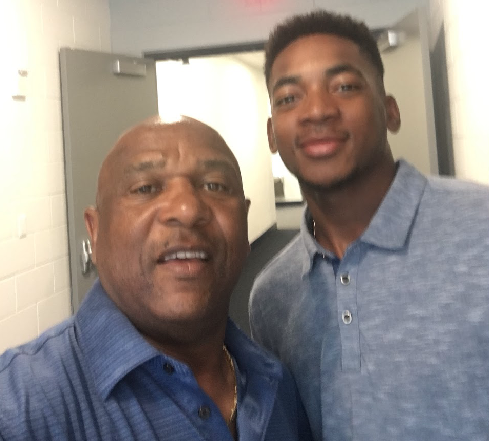

Terry Pendleton with President Jimmy Carter. Photo submitted.

Big brothers

Many young athletes look up to players who have come before. Pendleton’s hero was closer to home.

“Every young man mocks or watched their dad to see how he should grow up. My dad was my hero. He instilled the work ethic: You work your butt off, whether it’s in baseball or pulling weeds. You pull those weeds with the best possible effort you can give.”

“I had a lot of people in the Colonia-Rose Park area who I looked up to,” he continued. “I have a list of names, I have to put them all in there.” He lists people older than him, those who played basketball, football. “The way they carried themselves . . . they always gave me something to continue to strive for, they were all like big brothers to me.”

Coming to Oxnard from South Central Los Angeles, Pendleton had a different perspective on the Colonia neighborhood than many.

“There was nothing really tough about Oxnard, other than mom and dad trying to make a living, putting food on the table and clothes on our backs,” he said. “We had areas to go play, people you knew were good and bad. I learned I had big brothers there to take care of me, to teach me right and wrong, to tell me whether I was right or wrong.” That village helped ensure “I was going in the right direction at whatever I choose to do.”

Throughout his athletic career, Pendleton said that the “toughest thing, I was battling every day . . . I was never the biggest guy on the court. I always had to try and prove myself. I was one of the smallest kids around.”

Pendleton’s other great love was football, which he started in Pop Warner. His final year in football was his high school senior year, which turned out to be a good thing . . . for more reasons than one. “I got concussions on the practice field. Nobody knew it but me.”

The mental game

Thinking over the course of a career in the highest levels of his sport, Pendleton recognizes the ongoing toll on the body and the stamina needed to persevere through the “physical grind.” But the former MLBer insisted that the key to success lies in a very different kind of strength.

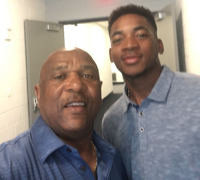

Terry Pendleton (left) with Darius Vines, an Oxnard College alum, currently pitching in the minor leagues for the Atlanta Braves. Photo submitted

“The mental aspect of it is the tougher part, it truly is . . . Everyone thinks it’s all about the physicality, you gotta be big and strong.” Pendleton acknowledged that physical strength is important, but to be able to mentally and emotionally “take the grinding every day . . .16 games every week, playing and getting hurt, the wear and tear and pounding on your knees. Anybody who’s played professionally knows.”

Players had to develop a mindset that would see them through the “ups and downs” of playing, of the grind, day in and day out. Even when you’re playing a sport you love, the physical toll and mental pressure to do well, to come back after setbacks or a bad day, is challenging. Pendleton credits a strong mental mindset that turns those negative events into learning experiences with getting him through the ups and downs of playing professional baseball.

In his view, “Today the mental part is getting more and more fundamental.” Players have to be “smart now, too,” noting that the sport, the media and the pressure “test you at all levels,” and require the “mental capacity to hold on and fight.”

A major part of his work today, as a coach, is mentoring young players not only in building their skills on the field, but also in their minds.

This year, the team he’s coaching, the Atlanta Braves, won the World Series. “It was rewarding to sit back and watch . . . The first baseman, second baseman, short stop . . . to watch those kids grow up . . . I mostly just stay out of their way, jump in when called upon . . . I’ve seen them grow up, from kids to young men to men on the baseball field.” With the win and ongoing success, he sees those players “reaping the benefits now of all the hard work and labor they put into the game.”

Players work to progress and continually improve. Even in the major leagues it’s expected that new players might be out of their depth and comfort zone. His approach to coaching is about coming in when a player isn’t progressing anymore. And sometimes the pressure of the game brings out the skill that has been in development in practice.

As for the future of the team, he said, “This team has not even started playing yet. They are much better than they’re showing.”

Currently Pendleton is the special assistant to baseball operations for the Atlanta Braves. That means he mostly “bounces around the minor league,” working with new draft picks.

“I love my job right now. I get to put on different hats at different times. I don’t have to be at the majors. If a kid is struggling, I go see them to get them on track. It is really rewarding for me. I get to be home for birthdays. When you’re with the major league you go on that schedule and that’s it.”

When asked if he plays at all now, he laughed. “No, ma’am.” During the Braves’ Fantasy Camp in 2017, “I was at third base. Two balls were hit really hard at me. I caught them. But I really realized how old I am.”

Without any regret he explained that today he knows “what my limitations are. I know how my body feels with arthritic knees. I just want to enjoy life, without all the unnecessary pounding on joints and muscles.”

He’s able to get his baseball fix through coaching, work that brings him satisfaction, knowing he is helping young players and giving back to the sport.

“Knowing the kids that wanna be sponges, soak up all the knowledge. That’s where I get my thrill. We work on something, and it comes out in the game, [the player] comes back with a big grin on his face . . . I get joy, basically, from giving back.”

“Every day you show up”

Pendleton says it’s been a while since he visited his old stomping ground in Oxnard. He and his wife have family in the area and “we try to get back every year, sometimes twice a year. But life moves on, you can’t get it to stand still.”

When asked about whether he has any thoughts to share with aspiring athletes in Oxnard today, he said, “Listen, as I tell the big leaguers . . . every day you show up. In the classroom, on the court there are two choices you can truly control. No matter what anybody else says, every day, at home, out with buddies, on a practice field, your hustle and your attitude. You can control those two things.”

When a coach or parent gets mad you can decide to “brush it off and keep going . . . walk out with a positive attitude.”

He also offered a word for parents. “If you can afford it, please allow kids to play whatever they choose to.” He gives an example of a young, skilled player who has only played baseball since he was 5. “It’s like a job already to him . . . just going through the motions. The whole deal could be that the kid is the greatest wide receiver to never play football because you never gave him the opportunity to do so.”

He lamented the cost of playing sports today, making it hard for working families.

“Kids are looking for fun. Every game is not win, win, win,” it’s about improving skills. “Yes, winning is part of growth, but so is losing. I lost an awful lot of baseball games. That’s part of growth. Losing can make you work harder to get winning.”

The Oxnard College baseball field today lists alumni legends. Photo courtesy of Oxnard College