- A Swiss company has manufactured a suicide pod meant to make voluntary death a painless—even euphoric—experience.

- The pod uses nitrogen gas to cause death.

- After death, the biodegradable pod can be used as a coffin.

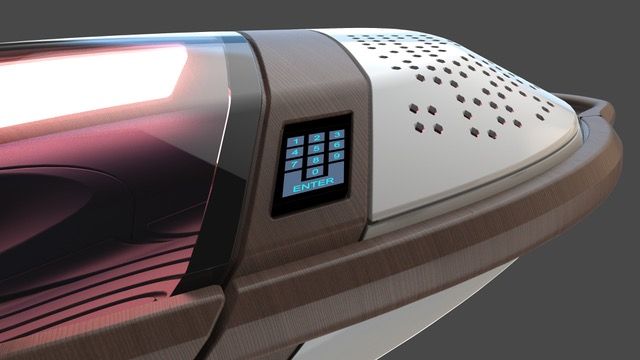

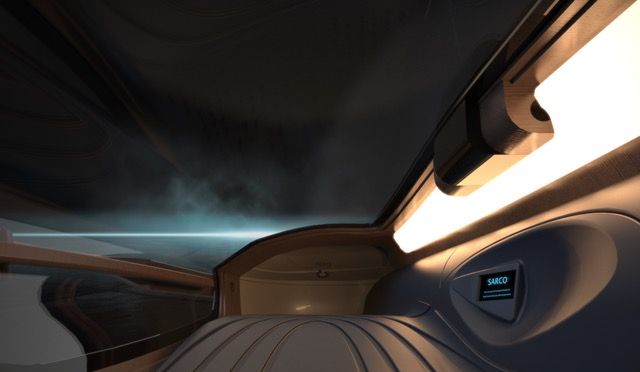

Imagine getting into a futuristic, purple, 3D-printed capsule. You lie down comfortably inside it. Then, an intercom system asks you some very simple, ice-breaker questions: “Who are you?” “Where are you?” “Do you know what happens if you press this button?” Once you’ve answered the questions, you are free to press the big, red button featured prominently to your right. Ten minutes later, you will not be in space—as you might be imagining—but safely on the ground. Technically speaking, you will not be at all.

Instead, this capsules transports you to death. Exit International, a Winnellie, Australia-based nonprofit, designed the so-called Sarco (short for sarcophagus) suicide pods. The company advocates for the legalization of both voluntary euthanasia (where a person’s life is finalized at their own request to relieve pain and suffering) and assisted suicide (suicide committed with the aid of another person, usually a physician). Its suicide pods recently got the legal green light from Switzerland’s medical review board.

“It does have that futuristic look as though it's a vehicle that would keep traveling or carrying us somewhere,” says Philip Nitschke, founder of Exit International. “It adds a sense of celebration and ceremony to a person's death,” he says.

Sarco works like this: when you press the death teleportation button, a canister of liquid nitrogen, which sits inside a stand tucked below the capsule, floods the interior with nitrogen gas, causing oxygen levels to drop to less than five percent in one minute. Unlike gas chambers, in which the person inside inhales poisonous gases (like hydrogen cyanide or Zyklon B), inert nitrogen is not toxic and it has no smell. In fact, nitrogen actually comprises 78 percent of the air we breathe. When you inhale pure nitrogen, though, it’s conducive to feelings of disorientation and slight euphoria, akin to how you might feel if you were inside a plane cabin that suddenly depressurized. Ultimately, death comes along as a result of oxygen deprivation and a hyper-concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood in ten minutes max.

The biodegradable Sarco pod, made from wood-based material, can also detach from its base and serve as a coffin. You can position this sci-fi-like, end-of-life vehicle by the sea, by a cliff, inside a room full of loved ones, or wherever else you feel like spending the last few minutes of your life.

There are currently three Sarco suicide capsules in the world. The first is on display at the German Museum for Sepulchral Culture in Kassel. The second is in Exit International’s laboratory in the Netherlands. In the same country, specifically in Rotterdam, the company is currently in the process of 3D-printing its third capsule. “The one in Germany is blue. The one in my laboratory is the color of the actual printed material, and the one that is being printed will probably be purple,” says Nitschke.

Exit International will soon ship the purple pod to Switzerland, where the first person wanting to die this way is patiently waiting. “Purple is the color of dignity,” Nitschke says. He and his team had been worrying whether they were making the capsules “too attractive.” “But I don't think one's death should be unattractive,” he says.

Assisted suicide with “unselfish” motives has been legal in Switzerland since 1942; in 2020, about 1,300 people turned to euthanasia organizations to end their lives. Though many people routinely travel to Switzerland due to its relatively lax attitude toward assisted death, Nitschke says the whole process is still slow. Under Swiss law, psychiatrists are the experts who must decide whether a person has the mental capacity to proceed with assisted suicide or not.

“Psychiatrists bring with them their own particular prejudices and beliefs. Artificial intelligence (AI) has the option of removing the variability and bias we occasionally see,” Nitschke says. He and his team are in the process of developing an AI program to establish whether a person has the mental capacity to commit assisted suicide, but they are experiencing “delays,” he says, alluding to the mainstream psychiatric establishment and its view on assisted suicide. His organization’s end goal is to demedicalize the assisted dying process entirely.

Yet for experts like John Hooker—professor of operations research and business ethics and social responsibility at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh—an AI can neither understand a person's state of mind nor communicate with them on a level “deep enough” to help them make these types of grave decisions. “It's not enough simply to make the correct response to questions. You have to make an assessment that this person is in his right mind, and has a coherent and intelligible rationale or explanation or justification,” Hooker says.

Regardless of the gargantuan ethical debate that is bound to accompany the Sarco capsule, particularly in countries like the U.S., it’s the most humane way to go, Nitschke suggests. You don’t have to put a needle into your vein to let drugs flow into your body, and you don’t need to gulp down drugs that might make you vomit, as is the practice in some clinics in Switzerland, according to Nitschke.

But what if someone changes their mind? “They don't press the button,” he says. The capsule is not locked, so you can simply climb out of it. But if you press the button and then change your mind, you won't have much time for regrets—in less than one minute, you will be unconscious.

Although the fancy Sarco capsule will not blast you off into space, it will take you on a different kind of journey—into the Earth.

Stav Dimitropoulos’s science writing has appeared online or in print for the BBC, Discover, Scientific American, Nature, Science, Runner’s World, The Daily Beast and others. Stav disrupted an athletic and academic career to become a journalist and get to know the world.