One month ago in Invercargill, New Zealand, a massive cardiac arrest stopped my dad Richard mid-conversation while raving away to his grandnephew Finn. Twenty minutes without sufficient oxygen left him with catastrophic brain damage. Richard lasted 10 days off life support, but his unbridled enthusiasm was extinguished that day. I thought I’d never hear his voice again … until I did.

Trapped alone for a week in New Zealand’s shambolic hotel quarantine system, the horror of seeing my incapacitated dad through Zoom’s digital veil was too much. And receiving only his laboured breath down the phone line made it hard to verbally articulate my love and gratitude – the only way I could was through playing him music. Often those songs were written by one of his heroes, Nick Cave.

A road trip through New Zealand’s North Island is my first memory of Richard playing me Cave’s music – a CD of 2001’s No More Shall We Part. Having just moved on from the soundtrack to South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, the experience was revelatory. Hearing Cave’s strange music as we sped past tī kōuka trees and greying fence posts was the first time I really thought about music – as a music writer I now do that a lot.

No More Shall We Part ushered me out of adolescence. I discovered The Boatman’s Call in my mid-teens and bought the Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus double album on its release in my first year of adulthood. Encountering Cave’s music was inevitable but it’s forever inseparable from memories of my father.

I spent my first night in Invercargill alone with Dad at Southland hospital, where I continued my musical vigil curled up in a La-Z-Boy chair. I played Cave’s boisterous Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! to lighten the mood until Richard’s groans intensified, prompting a call to the nurses out of fear I’d instigated his final boogie.

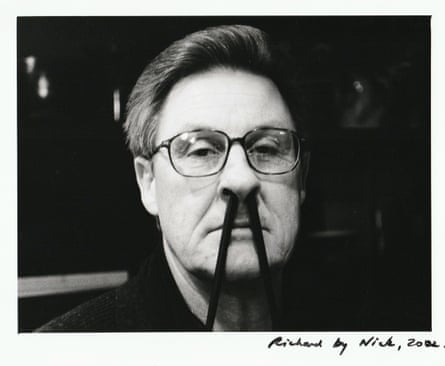

Music – along with photography – was Richard’s great joy. The variety of music he exposed me to is the foundation of my music writing (I’m a photographer, too). His interest wasn’t manufactured for others, coming instead from an unrelenting curiosity in the world’s creations. While in the womb he played me Tom Waits; he blasted me with Beethoven’s 5th at five days old and I blasted puke right back. Our house was filled with Dr John’s Creole incantations, the Ethiopian jazz great Mulatu Astatke, Taj Mahal’s intercontinental blues and Bonnie Raitt’s perfect I Can’t Make you Love Me.

I compiled that music to play at Richard’s cremation. Dad loved receiving my recommendations as our friendship grew with age, so I included music important to me too: Charles Bradley’s aching soul cover of Black Sabbath’s Changes; and Musicology by Prince, an artist I’d inspired him to re-evaluate.

Picking the perfect Cave track proved fraught until Google unearthed a live recording of Push the Sky Away, the encore of the last concert Dad and I attended together – Nick Cave and Warren Ellis playing their film scores with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra at Hamer Hall. Cave conducted and quipped while Ellis twirled in symbiosis with his violin. Richard wept that night and soon so would I.

I decided on Push the Sky Away to close the playlist at Richard’s cremation, only realising on the morning of the ceremony that the recording was from the very concert we had attended. Sun filtered through a chapel window crusted with salt from Dunedin’s Andersons Bay, illuminating a few family members seated over two rows of pews, roses from my cousin’s garden and Richard’s simple pine casket. Hunched over and sobbing, my hands cupped cheeks sticky with grief.

But as my tears swelled with the orchestra’s strings, and the crowd’s applause escalated with the choir, I encountered something miraculous. In that moment I realised my dad was roaring somewhere in there too, with me by his side, howling together with pure, overwhelming joy.

Nick Cave’s music has bestowed Dad and I with many gifts but none greater than this – the most profound musical experience of my life, an ecstatic transmission containing what I considered lost, the chance to hear Richard’s voice one last time. I can bring Dad to me now, any time I need him.