The 2021 Outsiders of the Year

It’s been another challenging year, but some people thrive on adversity. Here are the athletes, activists, tree planters, chefs, filmmakers, and other disrupters who changed our world for the better in 2021. Plus: Meet Carissa Moore, surfing’s first female olympic gold medalist.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Allyson Felix

The winningest track and field athlete is far more than a fierce competitor

Beaming from the podium after clinching victory in the women’s 4×400-meter relay at the Tokyo Games, this speed queen had plenty to smile about. With that gold—her 11th career medal—she replaced Carl Lewis as the most decorated American track and field athlete of all time. Here are four more reasons why Felix reigns supreme as running’s GOAT.

She stands up to running-industry inequality.

After longtime sponsor Nike shot down her request to include pay protection for its pregnant athletes, Felix broke her nondisclosure agreement to pen a damning op-ed in The New York Times in May 2019. Three months after Felix quit, the sportswear giant updated its policies.

She takes it all the way to the top.

Felix testified at a 2019 congressional hearing on racial bias in maternal health care, which contributes to increased complications and mortality rates for Black mothers. She’s continued to speak up to raise awareness, but the issue is also personal: while pregnant with her daughter, Camryn, Felix developed severe preeclampsia, a dangerous condition that prompted an emergency C-section at only 32 weeks.

She champions women.

Over the summer, Felix teamed up with new sponsor Athleta and the Women’s Sports Foundation to create a child-care grant program through the Power of She Fund, which is disbursing $200,000 to mom athletes, including nine Olympians so far.

She is a bold entrepreneurial force.

Without a shoe sponsor on the eve of the Summer Games in Tokyo, Felix decided to become her own, launching athleisure brand Saysh in June and smashing that Olympic record in a pair of her own custom kicks. Nike who? —Shawnté Salabert

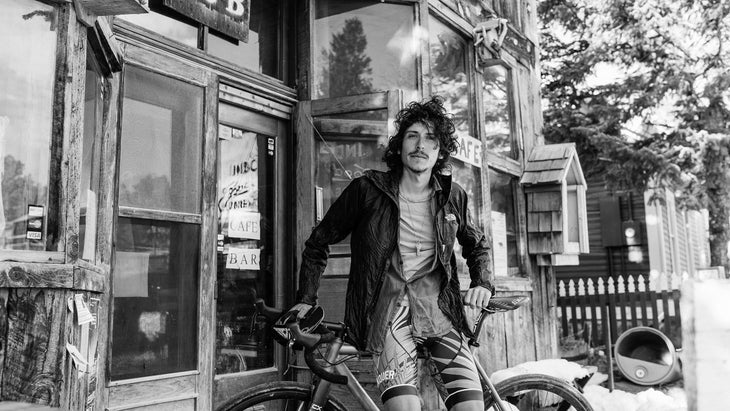

Lachlan Morton

The aussie who rode the 3,400-mile Tour de France—solo

On the afternoon of June 26, roughly an hour after the 184 official starters in the 2021 Tour de France rolled out from the Grand Départ in Brest, a solitary figure rode his bicycle across the starting line. He wasn’t late, nor was he an impostor. Pro cyclist Lachlan Morton was setting out on his own quest: to ride all 21 stages of the route, plus the 1,300 miles of transfers in between (which racers cover via team bus). He dubbed it the Alt Tour and turned the ride into a fundraiser for World Bicycle Relief, which donates bikes to people in need. Marrying bikepacking and the spirit of the original Tour, he carried his own gear, camped along the roadside, prepared most of his food, and repaired his rig when it inevitably broke down. And he still beat the Tour’s racers to Paris by five days. Here’s a look at his incredible effort. —Joe Lindsey

3,424: Distance covered in miles

219,262: Elevation gain in feet

225 hours, 7 minutes: Total time on the bike

0: Rest days

350: Miles pedaled on the longest day

17,000: Calories burned during that 20-hour ride

5 to 6: Hours of sleep per night

9: Flat tires fixed

$694,000: Funds raised for World Bicycle Relief

Pete Mortimer & Nick Rosen

Codirectors of The Alpinist, a documentary about climber Marc-André Leclerc. It’s the best adventure film we’ve seen in a while.

Dara McAnulty

The teenage author channeling Thoreau

Dara McAnulty was just 14 years old when he began Diary of a Young Naturalist, one of 2021’s most notable nature-writing books. The memoir, originally published in the UK, narrates a year in McAnulty’s life in Northern Ireland as he and his family move into a new home and explore the surrounding countryside. Its tender observations draw on a wealth of knowledge about various topics, including science, natural history, and Celtic mythology, while documenting McAnulty’s work as a burgeoning climate activist. “All the grown-ups are telling us how amazing this generation of activists is, commending our actions on social media or in the press, while doing what themselves?” he writes. McAnulty, now 17, is autistic, and his storytelling is candid about the ways his autism shapes his encounters with nature, which he describes as a “refuge.” The book got rave reviews and won him the UK’s Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing. McAnulty quickly followed it up with a children’s book called Wild Child, published this summer. —Sophie Murguia

Matt Delaney

A librarian starts a gear-lending program

Forces of Good: The Gearhead Librarian Who Revived a Town

Millinocket, Maine, had been struggling for years following the closure of the local paper mill. Then an enterprising librarian acted on a big idea.At the public library in Millinocket, Maine, the lending period is three weeks for books, a week for DVDs, and three days for a fat-tire mountain bike. Late fees are twenty cents per day for books and a dollar for any of the library’s 700 pieces of outdoor gear, although in the four and a half years Matt Delaney ran the program, he never once charged one. “We didn’t charge for broken gear either,” he says. The 39-year-old launched the gear-lending program in 2017, in an effort to get more community members outside by removing cost barriers. For Maine residents, a library card is free. Delaney, who moved to Millinocket in 2016, was hired to reboot the library, which had been forced to shut its doors the year before, a victim of dwindling municipal budgets following the closure of the local paper mill in 2008. Unemployment had shot to 22 percent, and the town’s population had shrunk by two-thirds. Still, a local outdoor-recreation boom was underway, with tourists drawn by the designation of nearby Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument and the construction of some 30 miles of singletrack. Delaney was amazed that many locals had never been to Mount Katahdin, the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail, just 20 minutes away. He obtained the program’s gear from the Maine nonprofit Outdoor Sport Institute. Since the initiative began, the number of library-card holders keeps growing. Patrons have checked out its items, which range from kayaks to cross-country skis, 2,441 times, and the bikes have helped locals get to work or school. Gear-sharing programs are on the rise, with nonprofits like Get Outdoors Leadville, in Colorado, and the Mountaineers, in Seattle, offering similar scenarios. Though Delaney was hired away by a library in Bar Harbor in July, the Millinocket program remains in high demand. “Modern libraries need to serve their particular communities,” he says. “Loaning gear is something we are uniquely suited for.” —Frederick Reimers

Stephanie Catudal

The writer who soothed her cancer-diagnosed Husband—and a wider community

We are schismatic vessels but I don’t know where our cracks are, or how deep they will be. All I know is that in those fissures is a choice: dwell in the sadness that caused them, or be fortified by the love that will make us whole again.

Outside Member Exclusive

Learn more about Stephanie and Tommy’s harrowing journey in this Outside TV videoWhen Stephanie Catudal shared those words on Instagram in September 2020, the Flagstaff, Arizona, writer and mother of three had spent the previous two months hunkered down at the hospital where her husband—endurance athlete, trainer, and physical therapist Tommy Rivers Puzey—was tethered to tubes and machines. It would be two more months before he returned home. Puzey—known as “Rivs” to most, including college sweetheart Catudal—was diagnosed that summer with primary pulmonary NK/T-cell lymphoma, an uncommon and aggressive cancer. Catudal sat as devoted sentry, watching as his mind and body wilted during a medically induced coma, forced ventilation, and six rounds of chemotherapy. Her sole driving force, she says: “Keep Tommy alive.” Against grim odds, in January, Puzey, now 37, made it into remission. He’s grateful for the support he received but is uncomfortable being cast as the inspirational hero. That role belongs to Catudal alone. “Through this entire thing, Steph’s been my caretaker,” he says. “She’s shielded me from the reality of a very daunting likely outcome, and at the same time filled me with belief that we’ll 100 percent make it through this.” One thing that helped Catudal shoulder that weight was letting her emotions tumble out in a piercing blend of grief and hope that often landed on Instagram, where her reflections have drawn almost 90,000 followers. The response still shocks her. “I never wanted to sensationalize what we were going through,” she says. “Writing was probably the biggest thing I could have done to keep myself sane.” Puzey’s not surprised that so many people found her comments resonant. “She helps people feel safe in their lowest, most miserable state, but then reminds them of the potential they have until they see it themselves,” he says. At the moment, Catudal is working on a memoir and planning to run 22 miles across the Grand Canyon. Puzey is strengthening his mind and body in preparation for a bone-marrow transplant. Creating memories with their daughters is another priority. They’re living in the moment rather than fearing the future. “Love did some incredible, unspeakable things this past year,” says Catudal. —S.S.

Zahan Billimoria

The mountain guide shaking up the fitness world

Strong athletes get power from their muscles, right? Not quite, according to Zahan Billimoria, the Jackson Hole, Wyoming, founder of Samsara Experience. An Exum guide with decades of mountain experience, the 44-year-old works to promote efficient movement by focusing on proper alignment and the fascia that surrounds our muscles. “We want to help you reclaim your innate athleticism, and to understand and train patterns of locomotion,” he says. The program launched in 2020 with 35 athlete clients, including MMA fighters and professional mountain athletes. This fall, Samsara debuted standalone training programs, available online, centered on specific pursuits like running, climbing, and mountaineering. Billimoria and his coaches favor movement that might look more like physical therapy than a gym workout. “The goal of rehab and of high-performance training are the same: building capacity in the body where it’s lacking in order to move better.” —Abigail Barronian

Kami Rita Sherpa

25: Times 51-year-old Kami Rita has summited the world’s highest peak, including his 2021 climb. Twenty-five! That’s three more than anyone else.

R.J. Scaringe

The engineer who made electric pickups real

Let the history books show: the first electric pickup truck to enter production wasn’t made by Ford, General Motors, or Tesla. The R1T from Rivian began reaching customers this fall. Pickups are America’s best-selling—and most polluting—consumer vehicles, and to have the EV pickup debut not via an established auto giant but by R.J. Scaringe, a hitherto unknown MIT grad, is significant. Scaringe founded Rivian in 2009, after completing a PhD in mechanical engineering. Since then he has raised billions of dollars from investment firms, sovereign wealth funds, and rival automakers. He poached design and engineering talent from well-known brands, including Ford and British automaker McLaren, then rolled out an electric truck that’s cleaner and faster than any before it. And it’s made right here in the U.S. —Wes Siler

Naomi Osaka & Simone Biles

Thanks to their courage this year, we have a better understanding of how important mental health is alongside physical health, even for world-class athletes.